The real story behind Deliver Us From Evil

The new movie adapts the memoir of Ralph Sarchie, an ex-NYPD cop who moonlighted as a demonologist. But is there any truth to his wild claims?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's no safer way to market a horror movie than slapping on the phrase "based on a true story." Last summer, The Conjuring — purportedly based on a true story — was a surprise hit, grossing a massive $318 million on a measly $20 million budget.

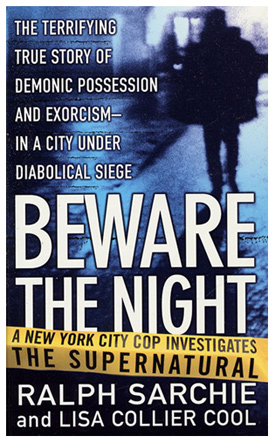

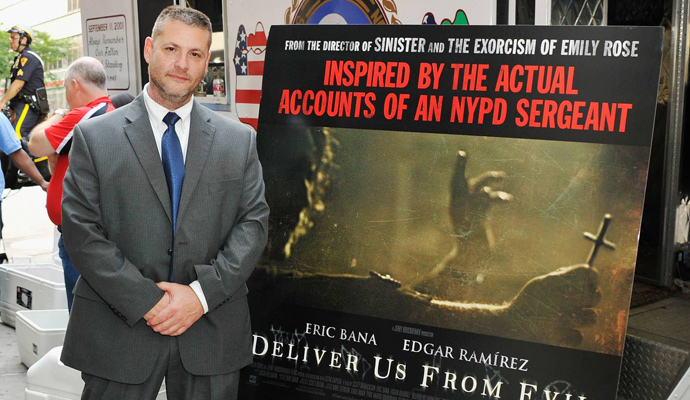

This year's equivalent is Deliver Us From Evil, a horror movie based on Ralph Sarchie's co-written Beware the Night, which he describes as a "memoir" filled with true stories about his work as a demonologist. It's a marketing angle that Sony is banking on; on the film's poster, the phrase "inspired by the actual accounts of an NYPD sergeant" are even bigger than the title.

Despite the claims of the marketing materials — and a lot of double-talk from the cast and crew — Deliver Us From Evil is almost entirely invented. "It’s the real Ralph Sarchie, how he thinks, how he talks, what he does, how he’s changed as a person as a result of the stuff he does," explained director Scott Derrickson in an interview with Complex. "But the main storyline is fictional, and I had to do that in order to make it work as a movie."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Beware the Night is a strange book. Though he pays lip service to his own sins, Sarchie eagerly casts himself as a tough-guy cop/demon hunter who wouldn't seem out of place in a Vertigo comic. His family views his demonology as a divine calling; when Sarchie survived a severe illness he contracted when he was 10 months old, his mother Lillian saw divine intervention. "God left him here for some reason. To do something," she says.

"The truth is that I like to help people," he explains in the book. "As a committed Christian, I have a different mission: to bust the Devil and his demons." He claims to carry "a splinter of the True Cross." He interrupts a story of demonic possession for a bizarre aside about a time when he arrested a (human) criminal "with a little persuasion from [his] 9-millimeter semiautomatic." And when it comes to demonology, he's rigidly anti-science, objecting to any so-called parapsychologists who approach hauntings "with their cameras and gauss meters instead of holy water and relics."

But most of all, Sarchie wants you to know that his services are free. "When Joe and I handle cases as demonologists in our off-duty hours, we don't charge a cent for our services," writes Sarchie. "Helping people who have spiritual problems isn't a career for us — it's a calling." It's a detail that comes up in most profiles about Sarchie. "He never once charged for this work," reads the only bolded line in a credulous (and unbylined) interview at Vice. (Sarchie did concede, in an interview with The New York Times, that he bought a house in Long Island with the money he got for selling the film rights to his book.) He also brags that neither he nor his partner ever "sought publicity for our involvement in the Work." He does not explain why he abandoned this anti-publicity stance for his book or its Hollywood adaptation.

Unlike Deliver Us From Evil, Sarchie's book is a series of unconnected cases. It begins with "The Halloween Horror," the story of Dominick and Gabby Villanova, who claim they've been beset by a demon. Their troubles began in autumn, when Gabby says she saw a woman, standing in a cloud of white smoke, in the corner of her bedroom. No one else could see her, but Dominick says she began speaking through his wife. Eventually, Gabby's friend Ruth becomes drawn into the story, weaving an elaborate tale — supposedly cooked up by the demon — about a woman who was murdered on her wedding night, and whose fiancé was falsely accused of the crime. In the days that follow, Gabby says she saw the ghost of her father — a claim her 5-year-old son eventually echoes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The claims go on: Books flung at the walls, "moans and growls" from the basement, the word "HELP" written backward on the bathroom mirror. In one particularly nasty aside, Sarchie interprets the description of a furry-looking creature as an incubus intent on raping Dominick and Gabby's daughter Luciana. When Gabby eventually becomes possessed by the demon while Sarchie and his partner are in the residence, he concludes that they are "in the presence of one of hell's most dangerous devils" and relies on the name of Jesus Christ to draw it out again.

Sarchie has an explanation for everything that happens. The demon originally appeared in a cloud of smoke because demons "always give themselves away with some abnormality of appearance." No one else could see "Virginia" because the demon wanted to sow the seeds of "panic, confusion, and self-doubt." And the factual inconsistencies between the story "Virginia" tells and the genuine historical record are explained by the fact that "lying spirits will mix just enough fact with their disingenuous fictions to keep their victims hooked."

He never seriously entertains the idea that all of this has a non-supernatural natural explanation. The closest he comes is when he argues that the doorknobs he heard rattling are "proof that this wasn't a case of mass hysteria, as skeptics might argue." He never disproves — let alone acknowledges — the other proposed explanations for hauntings or possessions: Mental illness, brain glitches, temporary psychosis, or an out-and-out hoax.

I walked away from Beware the Night convinced that Sarchie believes what he's saying — but that doesn't count for much, since everything is filtered through his extremely dogmatic worldview. Unfortunately, objective evidence is far harder to come by. The only video I could find of Sarchie's process — a brief documentary that doubles as PR for the movie, complete with branded hashtag — was far less conclusive than his written stories.

A couple describes hearing unexplained "screeching" in the middle of the night a month earlier. Sarchie and his partner enter the room in question with a few of their customary tools: medallions, holy water, and a cross. "My heart started to race. It was palpitating. And I got this pain right here in my temple. And I get that when I'm in the presence of evil." He goes on to explain that a possession has taken place, without offering any insight as to how he reached that conclusion. More nonspecific claims about screams and scratches are described, but aren't captured by the camera.

More upsetting footage comes later in the documentary, when Sarchie shows off footage from an exorcism he helped perform in 1992. A woman, strapped to a chair, screams and spits at the men who surround her. Once again, Sarchie's evidence for "a genuine case of possession" is totally subjective: a look in the subject's eyes — "the window of the soul" — that convinced him she had been occupied by a demon. "That's when I started to realize that this stuff is not just a creature feature or a thriller theater — that this is actually real," he explains.

It's a claim no one, despite what the trailer or poster says, can make about Deliver Us From Evil. The movie "is a work of fiction based on aspects of my cases and aspects of my life. It has to be interesting," he concedes. But as far as I'm concerned, Deliver Us From Evil picked the dullest part of the story to expand upon. The interesting part of Sarchie's background isn't the lurid details about possessions and demons; it's the zealousness of the man who believes so deeply that he never even considers another explanation.

Scott Meslow is the entertainment editor for TheWeek.com. He has written about film and television at publications including The Atlantic, POLITICO Magazine, and Vulture.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day