Girls on Film: Maleficent is less progressive than 1959's Sleeping Beauty

Disney frustratingly undermined the truly revisionist story it should have been telling

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Angelina Jolie's horned visage has lured the masses to Maleficent — an effects-laden world of love, betrayal, battle, and redemption, promoted by Jolie-centric ads that promised a story in which all supporting characters were irrelevant.

But the movie tells a different story: a far more conventional one, in fact.

In its first act, Maleficent offers a dark, surprisingly adult exploration of rape and female mutilation. The fairy Maleficent meets and falls for Stefan (Sharlto Copley), a young human torn between his love for her and his quest for power. When the dying king offers the throne to the man who kills Maleficent, Stefan sets out to do it himself, schmoozing with his old love before drugging her and preparing to stab her. But Stefan's weakness prevents him from doing so. Instead, he chooses to mutilate her unconscious body, cutting off her wings (to use as proof of her death) and leaving her alone and bleeding on the forest floor. When she wakes, she screams and sobs in both emotional and physical pain as she discovers that her love betrayed and disfigured her.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

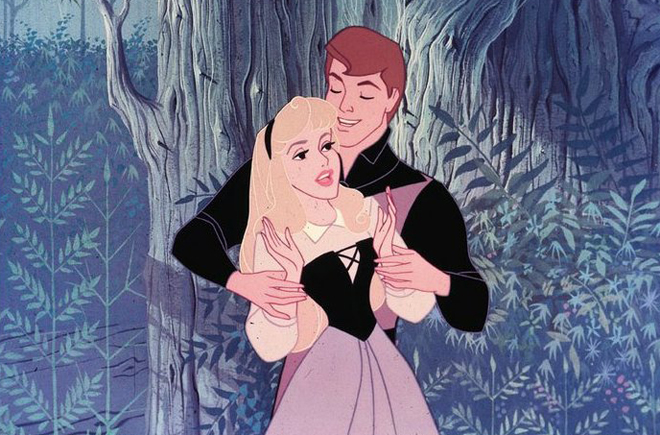

But after the brutal attack, Maleficent quickly retools itself, heading into a whirlwind of tones while ignoring the darker implications of its opening story. In a brisk 97 minutes, decades of narrative are distilled into boilerplate genre elements: The chills of a rape revenge fantasy, the mirth of slapstick, and the adrenaline of action. Just as Maleficent's wingless body ends up tied to the ground, her story is limited by the parameters set by the conventional Sleeping Beauty tale. This is because — despite the film's title — Maleficent's story is not her own after all. It is still Princess Aurora's.

As Maleficent's narrator, an older Aurora (who is the daughter of Stefan) explains that this is "an old story anew," one that was "not quite as it was told." But while the narrative could have offered a new story, it is still Aurora's, shackled by the inclusion of "not quite" rather than "much different." Motivations are changed so that Maleficent may become a villain-heroine, but Disney is only willing to stretch the boundaries of Sleeping Beauty so far. Where last year's Frozen had the freedom to explore sisterhood over romance, and follow that theme where it would naturally lead, Maleficent tries to fit the same femme-positive aesthetic into the original story's gendered restraints.

The result is the height of irony: to create a narrative of sisterhood that can exist within the original Sleeping Beauty, Maleficent diminishes and hurts its female characters. Aurora is given the gifts of beauty and happiness — but never intelligence, strength, or countless other worthwhile gifts that might have been bestowed in the third gift (which is never actually given). Indeed, Aurora is left with fewer skills than her 1959 predecessor. (Sleeping Beauty's Aurora was at least given the gift of song.)

In Maleficent, Sleeping Beauty's good fairies have been adapted into dangerous ditzes, who are inconceivably trusted with caring for the baby Aurora immediately after another fairy curses her. They are so terrible at the job that Maleficent is forced to watch over them, falling victim to her own revenge curse that "all who encounter [Aurora] will love her." The fairies even force the reluctant Prince Phillip to nonconsensually kiss the unconscious Aurora, hitting Sleeping Beauty's big plot point while uncomfortably ignoring the parallels to Maleficent's own bloody assault.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the film's treatment of Maleficent is even worse. Maleficent is viciously assaulted by Stefan. That's why she curses his daughter Aurora. It recasts the dark power she displayed in Sleeping Beauty as a mere reaction to a greater evil. But in this new film, the original curse — a true moment of female power — becomes momentary revenge. Her retribution is fleeting, with guilt and protectiveness soon replacing her thirst for vengeance. In the new film, Maleficent is even given a male conscience in Sam Riley's Diaval, so she may slowly lose her rancorous edge and regain her youthful whimsy as an unlikely Fairy Godmother.

In the end, Maleficent puts herself in danger for Aurora, and is beaten and tortured for it. Ultimately, as io9 so aptly put it, "Maleficent becomes a voyeur in her own life." As the film goes on, she doesn't act; she observes and reacts (and usually to men). Most egregiously, she doesn't even get to become the dragon she so memorably morphed into in Sleeping Beauty; instead, the powerful transformation is passed off to a man.

Maleficent clearly wants to be a member of Disney's new guard. Frozen challenged the romantic narrative, and Maleficent applies the same ethos to the company's past. On a superficial level, it questions the insanely profitable Disney Princess line and suggests that further revisionist tales might be on the way. The possibilities are endless: Did Ariel really give up her voice for legs and love? Did the Queen really try to poison Snow White?

But Aurora's "not quite" is an important turn of phrase. Some elements may have changed, but the heart of the story stayed the same, and Disney refused to give Maleficent her own truly empowering story.

In Sleeping Beauty, Aurora had a nurturing family and a trio of good fairies who were flighty (yet responsible). She had the gift of song, the man of her dreams, and an iconic, charismatic villain who audiences loved. In Maleficent, Aurora is the product of a cold and loveless marriage and a vengeful, unhinged rapist. Her safety relies on a trio of clueless and dangerously careless fairies, and her Godmother is the woman who cursed her — and who had, in turn, been violated by her own father.

Which sounds more reductive to you?

Girls on Film is a weekly column focusing on women and cinema. It can be found at TheWeek.com every Friday morning. And be sure to follow the Girls on Film Twitter feed for additional femme-con.

Monika Bartyzel is a freelance writer and creator of Girls on Film, a weekly look at femme-centric film news and concerns, now appearing at TheWeek.com. Her work has been published on sites including The Atlantic, Movies.com, Moviefone, Collider, and the now-defunct Cinematical, where she was a lead writer and assignment editor.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day