Skiing with the Dalai Lama

"If the Dalai Lama wants to go to the ski basin, we go to the ski basin"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

IN THE MID '80s, I was living in Santa Fe, making a shabby living writing magazine articles, when a peculiar assignment came my way. I had become friendly with a group of Tibetan exiles who ran a business selling Tibetan rugs, jewelry, and religious items. The Tibetans had settled in Santa Fe because its mountains, adobe buildings, and high-altitude environment reminded them of home.

The founder of the Tibetan community was a man named Paljor Thondup, who had escaped the Chinese invasion of Tibet as a kid, crossing the Himalayas with his family in an epic, multi-year journey by yak and horseback. Thondup made it to Nepal and then India, where he enrolled in a school in the southeastern city of Pondicherry with other Tibetan refugees. One day, the Dalai Lama visited his class. Many years later, in Dharamsala, India, Thondup talked his way into a private audience with the Dalai Lama, who told Thondup that he had never forgotten the bright teenager in the back of the Pondicherry classroom, waving his hand and answering every question, while the other students sat dumbstruck with awe. They established a connection. And Thondup eventually moved to Santa Fe.

The Dalai Lama received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. Thondup, who had heard that he was planning a tour of the United States, invited him to visit Santa Fe. The Dalai Lama accepted and said he would be happy to come for a week. At the time, he wasn't the international celebrity he is today. He traveled with only a half-dozen monks, most of whom spoke no English. He had no handlers, advance men, interpreters, press people, or travel coordinators. Nor did he have any money. As the date of the visit approached, Thondup went into a panic. He had no money to pay for the visit and no idea how to organize it. He called the only person he knew in government, a young man named James Rutherford, who ran the governor's art gallery in the state capitol building. Rutherford was not exactly a power broker in the state of New Mexico, but he had a rare gift for organization. He undertook to arrange the Dalai Lama's visit.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

He borrowed a stretch limousine from a wealthy art dealer, and he asked his brother, Rusty, to drive it. He persuaded the proprietors of Rancho Encantado, a luxury resort outside Santa Fe, to provide the Dalai Lama and his monks with free food and lodging. He called the state police and arranged for a security detail.

Among the many phone calls Rutherford made, one was to me. He asked me to act as the Dalai Lama's press secretary.

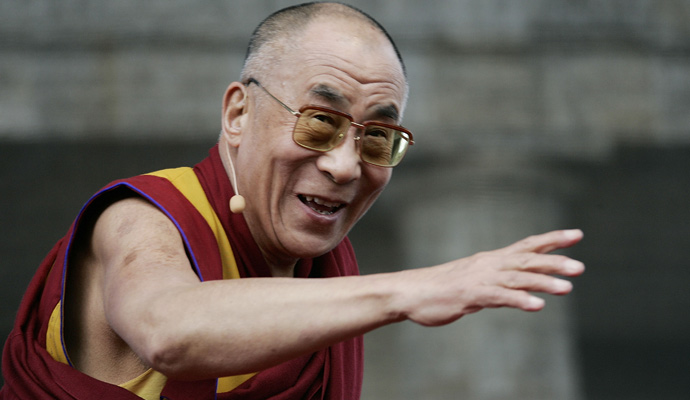

THE DALAI LAMA arrived in Santa Fe on April 1, 1991. I was by his side every day from 6 a.m. until late in the evening. Traveling with him was an adventure. He was cheerful and full of enthusiasm-making quips, laughing, asking questions, rubbing his shaved head, and joking about his bad English. He did in fact stop and talk to anyone, no matter how many people were trying to rush him to his next appointment. When he spoke to you, it was as if he shut out the rest of the world to focus his entire sympathy, attention, care, and interest on you.

He rose every morning at 3:30 a.m. and meditated for several hours. While he normally went to bed early, in Santa Fe he had to attend dinners most evenings until late. As a result, every day after lunch we took him back to the hotel for a nap.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Dalai Lama met politicians, movie stars, New Age gurus, billionaires, and Pueblo Indian leaders. During one luncheon, someone mentioned that Santa Fe had a ski area. The Dalai Lama seized on this news and began asking questions about skiing — how it was done, if it was difficult, who did it, how fast they went, how did they keep from falling down.

After lunch, halfway to the hotel, the Dalai Lama's limo pulled to the side of the road. I was following in Thondup's car, and so we pulled over, too. The Dalai Lama got out of the back of the limo and into the front seat. We could see him speaking animatedly with Rusty, the driver. A moment later Rusty got out of the limo and came over to us.

"The Dalai Lama says he isn't tired and wants to go into the mountains to see skiing. What should I do?"

"If the Dalai Lama wants to go to the ski basin," Rutherford said, "we go to the ski basin."

The limo made a U-turn, and we all drove back through town and headed into the mountains. Forty minutes later we found ourselves at the ski basin. It was the tail end of the ski season, but the mountain was still open. We pulled up below the main lodge. The monks piled out of the limo.

"Wait here while I get somebody," Rutherford said.

He disappeared in the direction of the lodge and returned five minutes later with Benny Abruzzo, whose family owned the ski area. Abruzzo was astonished to find the Dalai Lama and his monks milling about in the snow, dressed only in their robes.

"Can we go up mountain?" the Dalai Lama asked Rutherford.

Rutherford turned to Abruzzo. "The Dalai Lama wants to go up the mountain."

"You mean, ride the lift? Dressed like that?"

"Well, can he do it?"

"I suppose so. Just him, or…?" Abruzzo nodded at the other monks.

"Everyone," Rutherford said. "Let's all go to the top."

Abruzzo spoke to the operator of the quad chair. Then he shooed back the line of skiers to make way for us and opened the ropes. A hundred skiers stared in disbelief as the four monks came forward. I ended up sitting next to the Dalai Lama.

THE DALAI LAMA turned to me. "When I come to your town," he said, "I see big mountains all around. Beautiful mountains. And so all week I want to go to mountains." The Dalai Lama had a vigorous way of speaking, in which he emphasized certain words. "And I hear much about this sport, skiing. I never see skiing before."

"You'll see skiing right below us as we ride up," I said.

"Good! Good!"

We started up the mountain. The chairlift was old and there were no safety bars that could be lowered for protection, but this didn't seem to bother the Dalai Lama, who spoke animatedly about everything he saw on the slopes.

"How fast they go!" the Dalai Lama said. "And children skiing! Look at little boy!"

We were looking down on the bunny slope and the skiers weren't moving fast at all. Just then, an expert skier entered from a higher slope, whipping along. The Dalai Lama saw him and said, "Look — too fast! He going to hit post!" He cupped his hands, shouting down to the oblivious skier, "Look out for post!" He waved frantically. "Look out for post!"

The skier, who had no idea that the 14th incarnation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion was crying out to save his life, made a crisp little check as he approached the pylon, altering his line of descent, and continued expertly down the hill.

We approached the top of the mountain. The monks and the Dalai Lama managed to get off the chairlift and make their way across the mushy snow in a group, shuffling cautiously.

"Look at view!" the Dalai Lama cried, heading toward the back boundary fence of the ski area, behind the lift, where the mountains dropped off. The snow and fir trees and blue ridges fell away to a vast, vermilion desert 5,000 feet below, which stretched to a distant horizon.

As we stood, the Dalai Lama spoke enthusiastically about the view, the mountains, the snow, and the desert. After a while he lapsed into silence and then, in a voice tinged with sadness, he said, "This look like Tibet."

The monks admired the view a while longer, and then the Dalai Lama pointed to the opposite side of the area, which commanded a view of 12,000-foot peaks. "Come, another view over here!" And they set off, in a compact group.

"Wait!" someone shouted. "Don't walk in front of the lift!"

But it was too late. The operator scrambled to stop the lift, but he didn't get to the button in time. Four teenage girls came off the quad chair and were skiing down the ramp straight at the group. A chorus of shrieks went up, of the piercing kind that only teenage girls can produce, and they plowed into the Dalai Lama and his monks. Girls and monks all collapsed into a tangle of arms, legs, skis, and poles.

We rushed over, terrified that the Dalai Lama was injured. Our worst fears seemed realized when we saw him sprawled on the snow, his face distorted, his mouth open, producing an alarming sound. Was his back broken? Should we try to move him? And then we realized that he was not injured after all, but was helpless with laughter.

"At ski area, you keep eye open always!" he said.

We untangled the monks and the girls and steered the Dalai Lama away from the ramp, to gaze safely over the snowy mountains of New Mexico.

He turned to me. "You know, in Tibet we have big mountains." He paused. "I think, if Tibet be free, we have good skiing!"

WE RODE THE lift down and repaired to the lodge for cookies and hot chocolate. The Dalai Lama was exhilarated from his visit to the top of the mountain. He questioned Abruzzo minutely about the sport of skiing and was astonished to hear that even one-legged people could do it.

As we finished, a young waitress with tangled, dirty-blond hair and a beaded headband began clearing our table. She stopped to listen to the conversation and finally sat down, abandoning her work. After a while, when there was a pause, she spoke to the Dalai Lama. "You didn't like your cookie?"

"Not hungry, thank you."

"Can I, um, ask a question?"

"Please."

She spoke with complete seriousness. "What is the meaning of life?"

In my entire week with the Dalai Lama, every conceivable question had been asked — except this one. People had been afraid to ask the one — the really big — question. There was a brief, stunned silence.

The Dalai Lama answered immediately. "The meaning of life is happiness." He raised his finger, leaning forward, focusing on her as if she were the only person in the world. "Hard question is not, 'What is meaning of life?' That is easy question to answer! No, hard question is what make happiness. Money? Big house? Accomplishment? Friends? Or..." He paused. "Compassion and good heart? This is question all human beings must try to answer: What make true happiness?" He gave this last question a peculiar emphasis and then fell silent, gazing at her with a smile.

"Thank you," she said, "thank you." She got up and finished stacking the dirty dishes and cups, and took them away.

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in Slate. Reprinted with permission.