Don’t fret the falling tech stocks

Tech might be in for a hard landing, but the economy isn't

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

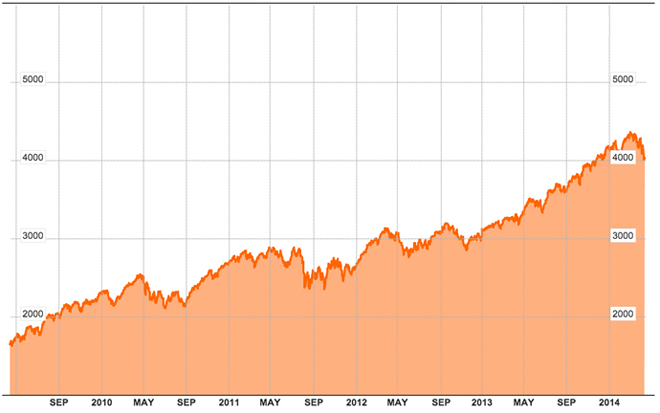

After climbing 244 percent from its 2009 low, the NASDAQ has dropped over 8 percent. It even fell 3.1 percent last Thursday alone, its largest single day drop since November 2011:

And while the dip since March looks pretty small in the broader context of the last five years, certain slices of the tech market have fallen more heavily.

Notable tech stocks like Facebook and Twitter have sunk 18 percent and 26 percent, respectively, since March. King — the maker of Candy Crush Saga — is trading for $16.96, far below the $22.50 investors paid for it during its IPO in March. Even tech behemoth Google has fallen 13 percent.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But nobody should be surprised that the NASDAQ and tech stocks are falling in price. As I wrote last year, the tech boom that saw companies with zero revenue like Snapchat get multi-billion dollar valuations was "a frenzy that can't last."

Why? Look at the profits of technology companies relative to their prices of their stock. Facebook's stock has a price over earnings (P/E) ratio of 97.55. Netflix has a P/E ratio of 176.2. Amazon has a P/E ratio 77.4 Google has a P/E ratio of 27.9. And Twitter actually made a loss last year, so has a negative P/E ratio. These are all far removed from the P/E of the Dow Jones Industrial Average of just 16. The prices of tech stocks like Twitter, Netflix, Amazon, Facebook and even (to a lesser degree) Google have all been driven by speculation based on projections of the future, not by actual business results.

Projections of the future are fragile, and often change. That means downturns in speculative stocks are to be expected, even if the longer-term trend is toward the upside.

What we should not mistake this tech downturn for is a foreshadowing of a broader market slump caused by the taper. The Financial Times argues that "[a] three week-long rout in technology stocks is fueling fears of a broader sell-off in equities as investors re-evaluate the risks they are prepared to take now the era of ultra-loose monetary policy is drawing to a close."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That argument contains some glaring assumptions. We're in an era of ultra-loose monetary policy? Then why is inflation barely above 1 percent — below the Fed's 2 percent target? If we're moving toward an era of higher interest rates, then we should expect to see inflation — or at least inflation expectations, which remain contained — rising significantly. The Fed has a mandate of full-employment and 2 percent inflation per year. The Fed isn't just going to "normalize" policy (i.e. raise interest rates significantly) because writers at the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal assume that that is the proper thing to do and especially if that "normalization" ends up crashing or otherwise destabilizing the stock market.

We know that the Fed under Janet Yellen is not in the game of trying to burst speculative bubbles. As Yellen argued in 2005: "it seems that the arguments against trying to deflate a bubble outweigh those in favor of it. So, my bottom line is that monetary policy should react to rising prices for houses or other assets only insofar as they affect the central bank's goal variables — output, employment, and inflation."

In other words, the Fed will raise interest rates to quell inflation, not to quell the rumblings of people worrying about a technology bubble. So if you're looking for significantly higher interest rates, watch for higher inflation. Don't just assume it's coming because you assume that the Fed wants to "normalize".

And even when higher interest rates do arrive, don't assume that higher interest rates will mean a downturn. The 1990s boom, for example, took place in a much higher interest rate environment than the one that existed today, fuelled by falling oil prices following the breakup of the Soviet Union. Cheap energy is a better fuel for an economic boom than cheap borrowing, because everyone consumes energy, but not everyone borrows. And with U.S. oil and natural gas production rising relentlessly, and the cost of renewable energy drastically falling too, there remains room for considerable long term optimism.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal