Yes, the gender pay gap is real

The question is what to do about it

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Yesterday was Equal Pay Day, an annual event to raise awareness of the gender pay gap. The date was chosen for a very good reason: Because women make 77 cents for every dollar men earn, the average woman would have to work an extra 68 days — from the start of January to April 8 — to earn the same amount as a male peer.

Yet some say that the gap doesn't really exist, or at least is much smaller than widely stated. Mark J. Perry and Andrew G. Biggs, scholars at the American Enterprise Institute, wrote an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal this week, suggesting that "the numbers bandied about to make the claim of widespread discrimination are fundamentally misleading and economically illogical."

They point to real factors that they suggest may underlie the differences in pay. First, men work more: "Men were almost twice as likely as women to work more than 40 hours a week, and women almost twice as likely to work only 35 to 39 hours per week." They argue: "Women who worked a 40-hour week earned 88 percent of male earnings."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Second, women drop out of the labor force to have kids: "The BLS reports that single women who have never married earned 96 percent of men's earnings in 2012."

But Perry and Biggs are not comparing apples to apples. It is perfectly logical to suggest that those who work longer hours, and those do not have children and concentrate on their career will rack up higher earnings. But the figures Perry and Biggs are citing compare women who work longer hours and who go unmarried to men in general. That is, women who work a 40-hour week earn 88 percent of the median wage for all men, including those who worked 40 or more hours, and those who didn't. And women who have never married earn 96 percent of the median wage for all men, including those who are married with large families and those who didn't marry and concentrated on their career.

And even with that brazen statistical fudge, women's pay still doesn't rack up to men's.

Perry and Biggs continue that "women often choose fields of study, such as sociology, liberal arts, or psychology, that pay less in the labor market."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And they go on to claim that men take riskier jobs, and so are better compensated for it: "Risk is another factor. Nearly all the most dangerous occupations, such as loggers or iron workers, are majority male and 92 percent of work-related deaths in 2012 were to men. Dangerous jobs tend to pay higher salaries to attract workers."

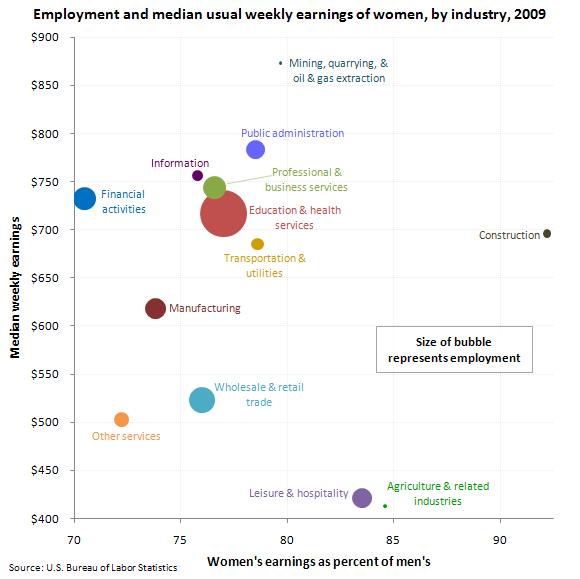

But actually, men earn more in nearly every field, not just ones which employee large numbers of women, and ones which are physically riskier like construction. As Bryce Covert noted in The Nation, men performing what have traditionally been seen as "women's jobs" make more than women do.

[Bureau of Labor Statistics]

So whether Perry and Biggs like it or not, the gender pay gap is very real across industries, and not just a matter of men taking more risk or women choosing the wrong industries. The causes are, I agree, probably more complex and systemic than the sexism of bosses.

For example, women pay the price for taking time off work to have children. In 2001, Karen Kornbluh calculated that women's earnings drop by 7.5 percent with a first child and 8 percent with a second. It also explains why the pay gap starts out small among younger men and women and then grows significantly as people get older and begin having families.

Why? One reason, as Joshua Holland argues, is that the U.S. is one of only three countries — along with Liberia and Papua New Guinea — that doesn't require employers to offer paid maternity leave. When American women leave their job to have a baby, their jobs often aren't waiting for them to return, leaving them to start again from the bottom of another company ladder.

Another reason is that men are more aggressive in salary negotiations and asking for raises. And yet another reason is that women are more likely to be burdened with looking after sick children or family members.

These are complex causes. And we must not forget that over the last 30 years, the gender gap has narrowed somewhat. But certainly, a leveler playing field for men and women — so that men and women doing the same job, over the same hours, are entitled to the same compensation — is a matter of basic human dignity, as well as something that regulation could fix relatively easily and cheaply.

Mandatory paid maternity leave would be a start — in Europe women generally get between 14 and 22 weeks of paid leave. As would mandatory paid sick days. And making it illegal for employers to retaliate against a worker who inquires about or discloses their wages or the wages of another employee in a complaint or investigation — as President Obama did by executive order for federal contractors and subcontractors yesterday — is sensible, too.

Editor's note: This article has been revised since it was first published in order to more clearly include proper attribution to source material.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day