The one part of the charity vs. social welfare argument that everyone ignores

It's called the status quo bias — and it's crucial to understanding our policy debates

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Mike Konczal has a wonderful article about "the voluntarism fantasy" in the latest issue of Democracy. Konczal takes on the claim that private charity once served the functions that social insurance programs now do, showing that there has never been a time since at least the Civil War in which the state was not engaged in significant social insurance provisions, and that charities, both in the past and present, become quickly overwhelmed during times of acute need. He concludes that charity cannot adequately replace social insurance, despite some conservative claims to the contrary.

Now, very few people publicly argue that our well-established social insurance schemes (think Social Security) should be uprooted in favor of charity. Hardly anybody claims that repealing Medicare would lead to a surplus of elderly health care charities. Fewer still come into the arena of public discourse claiming that cutting disability benefits would lead to an adequate network of disability mutual aid clubs.

Few argue these positions because once we have created institutions to ensure vulnerable populations are provided for, it becomes extremely difficult to explain why we should eradicate them. If you believe, as most claim to, that the aged and infirm should not die hungry on the streets, why exactly would you want to take their existing public benefits from them, give the money to other people instead, and then hope that those other people give it right back to the aged and infirm through charity? Even if it did somehow work out as planned, it would be a whole bunch of work to arrive at the same outcome.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

All of this is to say that when people think about these kinds of policies, they tend to do so through a status quo bias. When our existing institutions already neglect the sick, the aged, or the poor, it's easy to say that such things should just be handled with charity. But when our existing institutions do not neglect these populations, it is nearly impossible to say that we should install reforms that cause these people to be neglected, thereby creating social problems that charity can solve. Our views turn based on what our status quo institutions look like. It may be irrational, but this is a powerful feature of real-world policy discourse.

Consider how this plays out in the debate over providing insurance against childhood poverty, something the U.S. is woefully bad at. For this example, it is useful to compare the U.S. to a country that does a great deal in this regard, Finland.

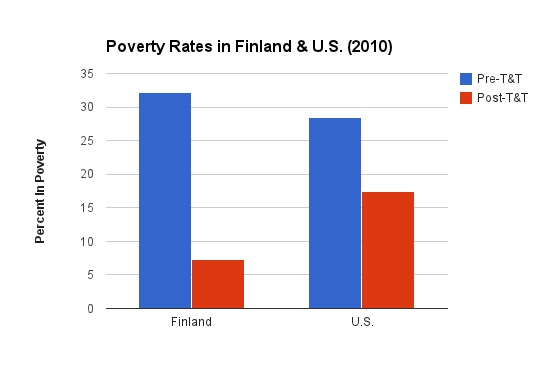

In Finland, the overall pre-tax, pre-transfer (pre-T&T) poverty rate was around 32 percent in 2010. But its post-tax, post-transfer (post-T&T) poverty rate was around 7 percent, a full 25 points lower. In the U.S., the pre-T&T poverty rate was actually lower than Finland's and stood around 28 percent. But due to our puny anti-poverty efforts, taxes and transfers only brought the U.S. rate down to 17 percent.

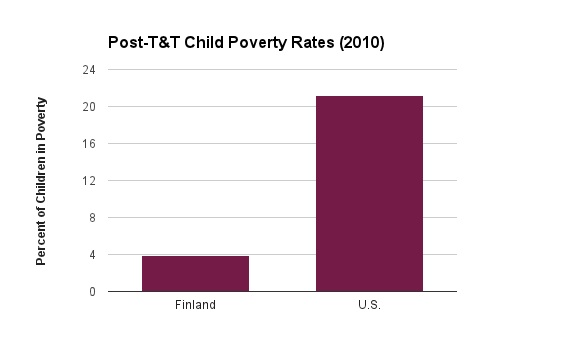

Because of Finland's robust transfer programs, Finnish childhood poverty stands among the lowest in the developed world, at 4 percent, while childhood poverty in the U.S. is among the highest at 21 percent.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Now try to imagine how the charity argument for solving childhood poverty would work within these two societies.

In the U.S., advocates of using charity might argue that we don't need more taxes and transfers and government programs. They would surely agree that a 21 percent childhood poverty rate is way too high, but that government handouts aren't the appropriate solution. We should ramp up charitable giving. That way, poor families with children can get extra food, clothing, and income from civic aid organizations. In a vacuum, it doesn't sound totally unreasonable.

In Finland, however, advocates of using charity instead of transfer programs would have to say something quite different. They would have to argue that sure, a 4 percent childhood poverty rate is really quite good, but that the way it's being achieved is all wrong. The better solution, they would argue, would be to ditch the transfer programs and then try to organize people to give money to charities to pull those children we just put into poverty back out of it.

Although the hypothetical American and Finnish charity advocates are basically arguing for the exact same poverty-fighting approach, the Finnish camp sounds crazy and cruel, and the Americans do not, because of the status quo bias.

There is one last compelling lesson here: All advocates of governmental solutions have to do is get enough support to push their policies across once. Then when that new status quo is established, the pro-charity argument for rolling back these entitlements appears utterly crazed — which it is.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day