Phantoms of the Hamptons

In one of New York's oldest settlements, a quirky town crier and his shy Wiccan wife revel in sharing 300 years’ worth of macabre local lore

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The wind has been relentless the last few days in East Hampton, but less than a mile from the crashing surf of Main Beach, it is eerily still in the South End Burying Ground. Three steps up a wooden staircase and three steps down into the old cemetery, barely a leaf is rustling on this October night. The only noise is a bat squeaking high in an oak tree.

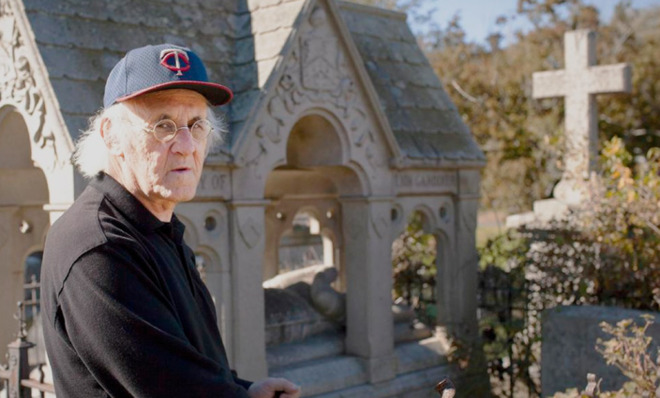

Hugh King, the official town crier of East Hampton, Long Island, is used to nights like these. He's been taking visitors on tours of the graveyard for 24 years, usually wearing a dark cape and top hat, or in warmer months, a vest over a purple shirt with puffy, ruffled sleeves.

The first thing a visitor might notice upon entering the cemetery from the north end is the towering marble obelisk in remembrance of the crew of the John Milton, who perished in a snowstorm in the winter of 1858, off the coast of nearby Montauk. Of the 33 sailors on board, 24 frozen bodies washed up onto what is now Ditch Plains Beach.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(More from Narratively: The secret life of a ghost hunter)

The ship was on its way back from the Chincha Islands in South America to New Bedford, Massachusetts. It was carrying guano, or bird droppings, to be used a fertilizer, King explains, sitting at his desk inside the Home Sweet Home museum, a simple wooden lean-to that showcases the town's history, and is located just down the street from the cemetery.

Not long before the ship crashed, a new lighthouse had been built at Ponquogue Point in Hampton Bays, but "Captain Ephraim Harding didn't know this," King says. "He thought the flashing light was Montauk Point and he crashed the John Milton into the rocks."

The town, ever so gracious, raised money to bury the crew, but since the dead were outsiders, they were buried on the edge of the coffin-shaped cemetery.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

King's litany of graveside monologues is peppered with shipwrecks, witch trials and disease, but the retired grade-school teacher favors history more than goblins and ghouls. He is more than pleased to recite his myriad of macabre local historical tales again and again, as long as people are willing to listen.

The South End Burying Ground covers four blocks between James Lane and Main Street. There are nearly 800 gravestones within the confines of the cemetery's well kept, albeit lichen-covered, picket fence, King explains, some dating as far back as the seventeenth century.

King's cemetery tours are very popular, especially around Halloween when sought-after slots fill up quickly. Reservations are a must then, along with flashlights. The uneven ground slopes down to Town Pond and the only other light sources are the distant street lamps and headlights coming in and out of town.

"It's not for young children," advises King.

Born in Brooklyn in 1941, King moved "back" to Amagansett, a hamlet within the town of East Hampton, with his family in 1947. His heritage dates to the town's founding days, but it was his ancestor Rufus King, a signer of the United States Constitution, who got him started on the road to becoming East Hampton's first Town Crier.

"Rufus King was a senator from New York, even though he was from New England," King says. "I dressed up as Rufus King, in 1987, as part of the festivities surrounding the 200th anniversary of the signing of the Constitution."

The Springs schoolteacher was such a hit with the community that the town supervisor at the time, Tony Bullock, asked him to become the official Town Crier. Not long after that, he was also appointed the official East Hampton Village Historian.

King co-wrote a column about East Hampton history, along with Sherrill Foster, for the East Hampton Independent from 1993 to 1998. The library may also publish a book King and his wife Loretta Orion are writing about the Goody Garlick witch trial, a subject Orion has studied extensively, as both an anthropologist and a member of the Wiccan Society.

King met his bride at the Royale Fish restaurant in Amagansett in 1979, now appropriately named the Meeting House, where King ran errands like picking up the daily fish for the owner while Orion was a server.

(More from Narratively: Living with the dead)

Orion, who grew up in New Jersey, had summered in East Hampton and worked as a private nurse in New York City. "Her last patient was the Shah of Iran," says King. "When his bodyguard began to interfere too much with his health care, she quit."

Orion headed east for her respite from nursing and joined the Wiccan movement. ("The religion of nature," King says.) As he tells the story of their meeting, Orion is just outside his office door, tending to the Home Sweet Home & Gardens. She makes short appearances to grab a gardening tool or utensil, and every time she enters, her husband rises from his chair as if meeting her for the first time. "Is everything okay?" he asks her. "Are you alright?"

It's obvious her spell over him has gone unbroken for the last 34 years.

Orion eventually got her Ph.D. in anthropology from Stony Brook University and taught courses in Witchcraft, Magic and Religion at Stony Brook, Hofstra and Suffolk County Community College. Her two papers on witchcraft will be combined with new information the couple has uncovered for their upcoming book about Goody Garlick.

You could say Garlick has become an obsession for the pair. On November 15, King and Orion, along with other actors, will reenact scenes based on Garlick's witch trial as part of a lantern tour down Main Street.

But the pair don't see the subject as a hokey holiday matter. "Witchcraft makes us smile, particularly at Halloween," Orion wrote in one of her papers, published in 2002. "The fact that thousands were tortured, burned or hanged to death, and their property confiscated, was not amusing in the 17th century."

King's background as a community theater actor from 1963 to 1999 serves as a boon to his crier abilities. His speech is quick, while his inflections cater to his audience and material. Upon answering the museum phone, his voice rises and falls to dramatic effect, from a flirty or teasing "Hello" to the feigned fear of "Goodbye." He has no problems stretching a word out for emphasis.

The couple assumed their roles at the Home Sweet Home museum in 1999. As Director, King gives tours inside the house, which was built in 1720, and she's in charge of the gardens. The site sits on the Mulford Farm property, where the settlement of East Hampton began in 1648. It was once believed that actor and playwright John Howard Payne, who wrote the famous song "Home Sweet Home!", was born in this house near the end of the eighteenth century. However, King dismisses that myth, which was likely first told by the farm's owner, Samuel Mulford. "Payne was born in New York City," King says. "His mother was from East Hampton and he had many connections here but he was not born here."

That didn't stop Gustav and Hannah Buek from buying the property in 1907 and creating a shrine to the songwriter by collecting every bit of memorabilia they could get their hands on. "When Buek died, his wife sold it to the village in 1927 and it's been a museum ever since," says King.

"They paid $60,000 for the house and all its contents," he adds, pausing for effect. Then, his voice rising, he blurts, "The entire village budget was $62,000."

King begins his cemetery tour just outside Home Sweet Home before leading his audience down the street and through the burial grounds, stopping at various gravestones.

"In England, they used to put the cemeteries next to the churches," says King, "When the Puritans settled here, they wanted to do eeeverything the op-po-site, so they put the cemetery in the middle of settlement."

The most elaborate tomb by far is that of Lion Gardiner, who died in 1663. His original grave was marked with cedar posts, something akin to the headboard of a simple bed. But he did not rest in peace. David Gardiner, a Yale-educated lawyer, decided his famous ancestor needed a more fitting resting place. Like an early farmhouse torn down to build a McMansion, Lion Gardiner's 6' 2" frame was dug up and his resting place renovated.

(More from Narratively: Up in the old asylum)

In his 1886 reincarnation, Lion Gardiner became a medieval knight — the personal stone structure where he now rests is topped by a statue of a man dressed in a coat of arms. Gardiner's new tomb was designed by James Renwick Jr., the architect behind St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City.

"He didn't need all the accoutrements," quips King, "I think the shoes are wrong too."

David Gardiner was buried near Lion, along with his father, also David — a New York State Senator — and mother Julianna. His sister Julia, though, was notably buried in Virginia.

As King tells it, "All of Washington society was after Julia and her sister Margaret, incloooding the President of the United States, John Tyler. The sisters went along with their father and other dignitaries, incloooding the President, on a pleasure cruise down the Potomac. The boat carried a new gun called the Peacemaker and there was an explosion. David Gardiner, the secretary of state, and six other people were killed. President Tyler was below deck, perrrhaaaps having a champagne cocktail with Jooolia, who faints. The President carries her off the boat and she becomes First Lady."

King takes a deep breath and releases it. "He was fifty-four, she was twenty-four. He had five children with his first wife Letitia, who died of a stroke, and had five more with Julia."

And if that wasn't enough, Julia dabbled in politics. "Ewww," King gushes. "Women were not supposed to be engaging in such things."

Cornelia Huntington, the town's first female author, was buried in East Hampton alongside her "highly intellectual" family. She wrote "Sea Spray," a 460-page novel, in 1857, under the pseudonym Martha Wickham, because the family lived in the Thomas Wickham house on Main Street.

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict