Kickstarting a cure for rare diseases

"Our kid was in there. The question was, how were we going to get him out?"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The geneticist called it a one-in-three-billion chance.

Just one. Out of three billion. Take a plane to Asia — absolutely anywhere in Asia — and randomly point to the first person you see. Is it Kim Jong-un, the fade-hairdoed leader of North Korea? Yes? Well, you've just beaten the odds we're talking about here.

But that's all the likelihood it took for Robert Stone — the only never-in-a-million-years, statistical screw-you that Robert's body needed to land him in a wheelchair and cause legions of medical know-it-alls to scratch their heads in wonder for 13 long and painful years.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(More from Narratively: If you see something, do something)

The outdoor terrace at the 2012 TED Conference in Long Beach, California, is spilling over with Sauvignon blanc and swagger. The crowd is thick with TED Fellows, the "young world-changers and trailblazers," as the organization calls them, behind geopolitical ventures, like one that creates fuel from Africa's agricultural waste, and highly lucrative ones, like a 3D-printing operation called MakerBot, which 15 months later would announce a merger worth north of $600 million.

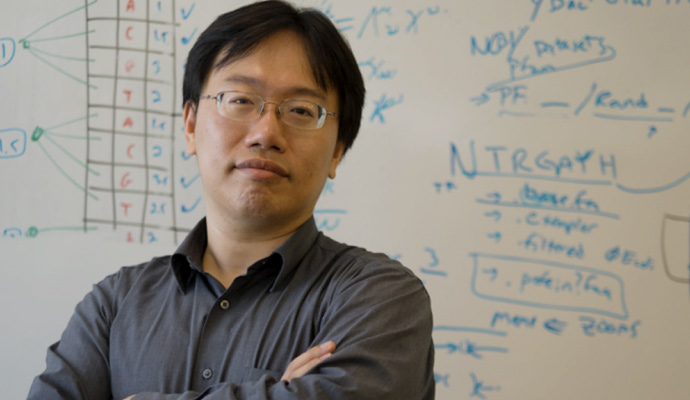

Jimmy Lin appears to float above the crowd, a boyish energy about him, a perpetual smile that just won't go away. And that says a lot, because Lin has seen things. He's studied patients, kids mainly, whose hopeless conditions would make any optimist wince.

Lin, 34, has mid-length black hair that parts just left of center; he wouldn't look out of place in an undergraduate science lab, or waiting in the pizza line at the dining hall. He becomes easily excited and animated, not necessarily qualities one would expect in someone who got his start in cancer research, as the lead computational biologist on a team that pioneered the genetic mapping of the disease in 2006.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"There were many, many inspiring stories of people fighting cancer, for sure," Lin would later say of his time at Johns Hopkins, where he received a dual MD-PhD in 2012. But despite his groundbreaking work, the young researcher had become increasingly haunted by an uncomfortable medical disparity: cancer claims nearly eight million lives a year, and attracts billions in federal research dollars, but multitudes more people — 25 million in the U.S. alone, and 300 million globally, by some estimates — suffer from rare diseases or disorders for which there are often no clues, let alone cancer-esque coffers of funding.

The universe of rare diseases is a fascinating and troubling place. It brims with maladies that have names like arthrogryposis, derived from the Greek term for "curving of the joints," and transverse myelitis, which can lead to a sudden loss of spinal cord function. Its patients are comprised almost entirely of children, since, as Lin gravely puts it, most people with such diseases "don't survive to become adults." It's a world in which mothers and fathers blog and pray, long after giving up hope for a diagnosis. You can forget about treatment.

Lin likens these parents to grossly underpaid and disturbingly hands-on Chief Medical Officers. "They're literally on-call 24/7 fighting for their kids' lives," he says. But in an era of medical marvels and untapped scientific talent, Lin saw an opportunity. So in the spring of 2011 he decided to donate his free time to the business of "trying to dissolve rare diseases" — all 7,000 of them.

It's a lonely business, with little in the manner of active research, since only a basketball team's-worth of people on earth might sport the same symptoms. So Lin's volunteer foray from cancer — where his career in academia is still focused — was tantamount to LeBron James's leaving the NBA's twice-reigning Miami Heat to moonlight on the practice squad of a youth team in Burundi: no face-painted fans, no private masseuse, no sports car; just endless work, veiled in obscurity — the windowless-basement type — with rarely a breakthrough in sight.

"If someone else is working on a disease we'll let that person attack it," Lin says. "We literally draw our area where there's no one else."

(More from Narratively: Tales from the $20 handouts)

Jeneva Stone keeps coming back to the video camera analogy. That's the only way she can make sense of what started happening to her baby, Robert, back in 1997, shortly after he was born.

"Something would happen," Stone, now 49, recalls, "and it would happen for 30 or 60 seconds, and he would be absolutely fine. And you would think to yourself, 'What did I just see?' Because your brain's not really a video camera, you don't really know how to replay what you saw."

At first, the symptoms were subtle flashes of decreased motor skill, like a spastic smear of food on Robert's cheek just as his spoon hit his mouth. Occasionally, there was nothing to even see — just a thud heard from the other room, an infant suddenly lying on the floor, motionless for a few horrifying seconds, a vacant look on his face, his muscles unnaturally relaxed.

"It was just like he'd been paused on a video, and you hit play, and the video just starts again. And he was fine, and he just started crawling again," Stone says.

The doctors simply chalked it up to colic — a healthy baby boy prone to occasional fits in which he'd grow fussy, start crying, and lose his balance.

Stone is a fast talker, but there's a soothing cadence to her voice. She's prone to bursts of laughter, like someone who hasn't been through what she has; like she's merely the matriarch of a typical suburban Maryland family with a devoted husband and two young kids. Maybe she's like this because of the hand she's been dealt, or maybe she's been dealt this hand because of who she is. How else could she cope with the years of tests, the inconclusive results, the accusations that "extreme parental anxiety" had led her to "invent" Robert's symptoms?

At one point, a group of mystified doctors decided that Robert had some sort of genetic disease that would end his life within three years. But Robert kept on living, and by the time the family took him to a neurological specialist at Johns Hopkins, he was experiencing periods of being "locked in" for hours. He had stopped talking and lost most of his motor function. A good day meant that Robert could sit up in bed for a minute or two at a time. The neurologist eventually exhausted all possibilities.

(More from Narratively: Five-star soup kitchen)

"I don't have anything more to add," he admitted to the family. "You should go see someone else."

There was no one else, no miracle answer — only more doctors, more drugs, more tests.

"My husband and I are both competitive, driven people," Stone says of herself and Robert's father, Roger, who runs his own direct marketing and data company. "We would be consumed with anxiety during tests for these horrible diseases and when they came back negative you'd feel like you won a prize."

A writer with a PhD and an MFA, Stone laughs as she recites a line from a blog post she once wrote, a string of words that form the basis of a memoir in progress:

"We are winning! If there are no answers, surely, we must be winning."

Except, there was no prize, no consolation. Every test that came back negative was a relief that Robert didn't have Tay-Sachs or muscular dystrophy, but also a reminder of the family's helplessness.

Robert, now 16, has been tube-fed since he was two because he can't swallow food without choking. He's been confined to a wheelchair since the age of four. Through it all, and even when things got really bad, Stone and Roger insisted that Robert was cognizant, that he understood where he was, and who his parents were, and what they were trying to tell him.

"He still seemed like our child," Stone says. "Our kid was in there. The question was, how were we going to get him out?"

Read more of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Media: Why did Bezos gut ‘The Washington Post’?

Media: Why did Bezos gut ‘The Washington Post’?Feature Possibilities include to curry favor with Trump or to try to end financial losses