How Wall Street is crushing Main Street

The "financialization" of the American economy is hurting local governments

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The conservative assertion that government spending "crowds out" private investment has been ascendant since Ronald Reagan's claim that "government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem." The idea is that the government is so big that it discourages private investors from competing in the marketplace.

Today, we face the reverse condition: the casino market that dominates the finance sector is crowding out important public investments. The deregulation of the financial sector — promoted by Republican and Democratic administrations — has changed America from an economy focused on sustainable growth toward a free-for-all for the wealthy.

This change is called "financialization." The financial sector has grown to almost 8 percent of GDP, from about 4 percent in Reagan's time. That the financial sector has grown isn't necessarily a problem; what is a problem is that it has grown faster than the rest of the economy. The purpose of the financial sector is to facilitate investment in a wide array of activities — to grease the wheels of the economy, so to speak. If the rest of the economy doesn't grow along with the financial sector, it is not fulfilling that purpose.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

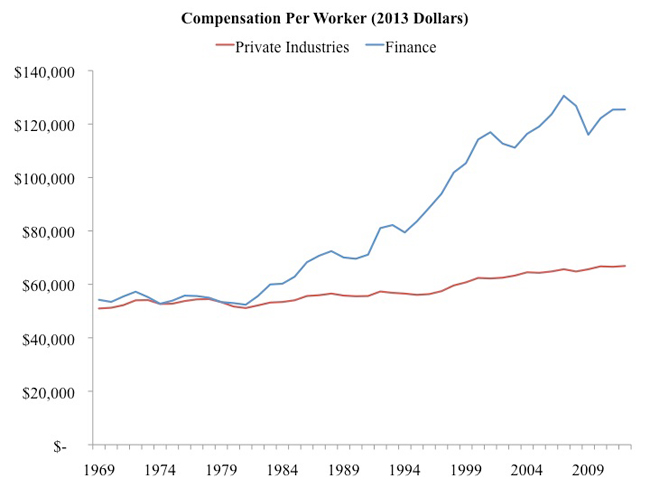

Financialization causes many problems. First, the financial industry is a poor producer of middle-class jobs, disproportionately benefiting high-end earners (see chart). Second, the financial industry is extremely myopic when it comes to economic trends. One study finds that the growth of the financial sector has decreased long-term investment in the real economy because financiers work in short-term gains and losses. Finally, financial "innovations" like securitization and derivatives have freed trading markets to grow unconstrained by the actual amount of stocks, bonds, and commodities in the real economy. One need only to recall the mortgage-backed market that crashed in 2008 to grasp the scope of this phenomenon.

A consequence of the rise of the financialization machine is that there is less money available for government investment in the real economy. Direct federal investment is already constrained by fiscal dysfunction, so indirect investment is even more important. When the Federal Reserve tries to pump up the economy through easy money, that easy money flows disproportionately to the supercharged investment in the financial sector. The banks end up using it to backstop trading businesses, rather than lending it to productive enterprises that generate jobs in the real economy.

State and local governments, already strapped by tax bases decimated by the Great Recession, have to compete with the financial industry, since investing in Wall Street is more profitable than investing in Main Street. The financial sector’s preference for the trading markets means that small businesses and households, the bulwark of state and local government tax bases, lose out in the competition for investment. As a result, critical public infrastructure investments have been ignored. One study estimates that our infrastructure system needs a $3.6 trillion investment over the next six years. In South Dakota, Alaska, and Pennsylvania, water is still transported via century-old wooden pipes. Large portions of U.S. wastewater capacity are more than half a century old. And in Detroit, some of the sewer lines date back to the mid-19th century.

Government investment in research and development has plummeted, and this will not be replaced by private investment that must compete with the short-term returns from capital investment in trading. The Financial Times reports that "public investment in the U.S. has hit its lowest level since demobilization" after World War II. That's a shame, because investments in science, for example, produce huge benefits, both in terms of well-being and economic growth. The Human Genome Project, for instance, cost 3.8 billion in public funding and has produced economic gains of $796 billion. That's a return of $140 to $1! The internet, too, was a product of government research and has produced tens of trillions of dollars in economic output and growth.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

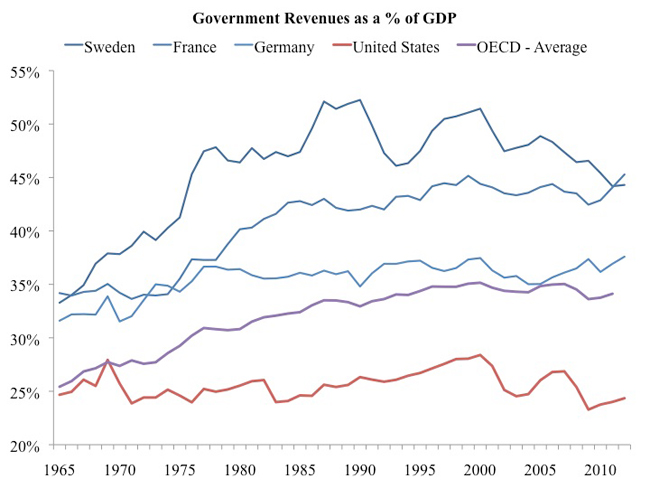

Public spending in the U.S. is far below the international average (see chart), and the rise of finance is part of the cause. By taking up a larger and larger share of the economy's resources and using them for the economic equivalent of roulette, we've allowed important public investments to be passed up.

This is simply unsustainable. Rabindranath Tagore once warned of "precocious schoolboys of modern times, smart and superficially critical, worshippers of self, shrewd bargainers in the market of profit and power" who, "driven by suicidal forces of passion, set their neighbors' houses on fire and were themselves enveloped by flames." Today, these schoolboys increasingly sit on Wall Street, diverting resources from the real economy into fat paychecks. The only question is when the economy will again be enveloped by flames.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal