Girls on Film: Why the Bechdel Test is still so valuable

Those who attack cartoonist Alison Bechdel's now-famous criteria for evaluating films have misunderstood its very purpose

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

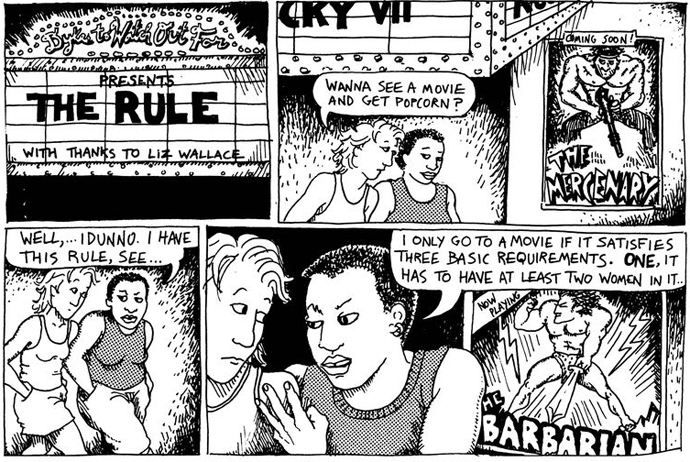

Twenty-nine years ago, American cartoonist Alison Bechdel immortalized her friend Liz Wallace's very simple and compelling rule for picking films, using her comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. In recent years, this idea has exploded, and "The Rule" is often at the center of much modern feminist cinema discourse.

In the original strip, a couple discusses whether they want to go to a movie and get some popcorn. One isn't sure, because she has a rule:

"I only go to a movie if it satisfies three basic requirements," she explains. "One, it has to have at least two women in it, who, two, talk to each other about, three, something besides a man." When her girlfriend says those criteria are good, but pretty strict, she responds, "No kidding. Last movie I was able to see was Alien. The two women in it talk to each other about the monster." Having walked past three uber-masculine posters for movies about mercenaries, barbarians, and vigilantes, the two women give up on the idea of a film altogether, and go home to make popcorn.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The sentiment wasn't new; as Bechdel later explained, it came from Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own. In the novel, Woolf's narrator responds to a surprising book she is reading. "'Chloe liked Olivia,' I read. And then it struck me how immense a change was there. Chloe liked Olivia perhaps for the first time in literature."

When it comes to female literary characters, "so much has been left out, unattempted," Woolf's narrator thinks. She struggles to think of texts that show women as friends, and marvels at texts that show women having "interests besides the perennial interests of domesticity." Sixty years after A Room of One's Own, those observations remained accurate, and almost 30 years after Bechdel's strip, they still are.

Unfortunately, those observations have also been subject to the frenetic and capricious whimsy of the internet. The internet is a place where beloved people and sentiments are tirelessly, repetitively, and sycophantically praised until the refrain grows tired and the death knell is rung. In time, what was once praised is picked apart and ridiculed — even if the original, important message has stayed the same.

As its fame has grown, Bechdel's Rule has been warped from its original purpose — a test that shows how rare genuine female interaction is on-screen — and reinterpreted as a means to reduce cinema. Today, merely mentioning it will lead people to complain about its flaws as a feminist cinematic gauge, because great films can fail and good films can pass.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There are countless complaints: "The test ends up telling us that the content of a film is more important than its form," argues one writer. It's "not without major flaws," and it's "next-to-useless, but also damaging to the way we think about film." The Rule is "too easy to satisfy in a superficial way." It's "a fairly crude metric" that is "hopelessly out of date and no longer the standard by which films with even the slightest feminist lean should be judged." It "sets the bar too low." "The test doesn't work."

It doesn't help that some describe it as a "sexism test," and that others herald it as a measure of worth. Now there are writers calling for feminists to create a new measurements, projects that have extended The Rule into a much longer 20-question test, and entire panels dedicated to critiquing The Rule and trying to evolve beyond it.

Much of today's backlash is due to a new "Bechdel Rating System" some Swedish cinemas are using, which gives an "A" to any film that passes the test — a movement with good intentions but a mixed message. Ellen Tejle, a director at one of the theaters launching the initiative, says it is not an "official seal of feminist approval. [...] We're only saying that there are a miniscule amount of films out there that have two women (with names) talking to one another about something other than a man." According to her, the ratings are intended to spark conversation about the paucity — not make a definitive declaration about a film's feminist worth.

For some, that paucity is merely an oversight. Screenwriter John August said he was "struck by how rarely the female characters actually do talk to each other" when he applied the test to his own work (Big Fish, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Titan A.E.). For others, it's a willful, systemic problem. The Hathor Legacy creator Jennifer Kesler revealed in 2008 that her film professors told her it was not okay to have multiple named women in her scripts, passing The Rule. After many requests for clarifications as to why, an industry pro told her: "The audience doesn't want to listen to a bunch of women talking about whatever it is women talk about."

The one-page comic that popularized The Rule boils down to one simple story: A woman was tired of seeing female interests narrowed to just men/romance, and chose to go without movies instead of perpetuating the problem. She wasn't saying films are only good when women have diverse conversations, and she certainly wasn't saying that passing her criteria automatically meant a film was good.

In fact, Bechdel's original artwork suggests the opposite; her characters clearly recognize the limitations of her Rule. The Rule-maker never says any conversation is enough, and she doesn't claim her criteria are a measure of a film's feminist elements. Initially, Bechdel's Rule-maker is smiling, with her brows arched and her shoulders raised as she recalls seeing two women talking about the monster in Alien. In the very next cell, however, her shoulders are hunched. She's clearly sad at the thought that a conversation about aliens made her excited — that it’s the only movie that has passed her test in the six years between the film and the strip. Bechdel picked a film with monsters, and explained The Rule on the backdrop of '80s macho movie posters. These choices make the distinction clear.

Compiling lists of films with feminist messages or lists of films made by women are not a valid counter argument because this Rule does not measure "feminist success." In fact, to counter The Rule with examples of great supporting performances ultimately reinforces it. Using highly skilled women who are secondary in male narratives shows why Bechdel wrote the comic in the first place.

The Rule is not a measure of "gender bias" in regards to a specific film, and to apply such thinking is absurd. It doesn't address plot, cast, or intent. Gravity director Alfonso Cuaron fought to retain his female lead when others wanted to make Dr. Ryan Stone a man; it fails The Rule not because of bias, but because there are only two characters. My Dinner with Andre fails because it is a conversation between two men, written by those men. Many great films fail for reasons that have nothing to do with bias. A film that fails can be fine — but a relentless onslaught of failures with few films that pass is not.

The Rule resonates because it touches on something so profoundly simple and lacking. It works because it's a genuine challenge even to find films that barely pass the test — and Ninja Warrior-difficult to find a good deal of quality cinema that passes with flying colors. It works because if you flip it to apply to men, it's difficult to find films that don't pass the test.

The problem isn't with The Rule as Alison Bechdel immortalized it. It's with the cult of fandom — with those so struck by the applicable simplicity of the test that it has been built up to be something it's not and was never intended to be. The Rule works because it shows Hollywood's overall allergy to showing women having diverse conversations, and the audience that Hollywood loses as a result.

The strip is about a woman who stopped seeing movies because they ignored the worth of women outside of the context of men. It's about someone who chose to go without rather than see her gender reduced. All the character wants is to see women talking — and the failure isn't with her, it's with those who won't listen.

Girls on Film is a weekly column focusing on women and cinema. It can be found at TheWeek.com every Friday morning. And be sure to follow the Girls on Film Twitter feed for additional femme-con.

Monika Bartyzel is a freelance writer and creator of Girls on Film, a weekly look at femme-centric film news and concerns, now appearing at TheWeek.com. Her work has been published on sites including The Atlantic, Movies.com, Moviefone, Collider, and the now-defunct Cinematical, where she was a lead writer and assignment editor.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage