A defense of clichés

Bad journalism doesn't come from bad writing

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Writing is a tricky business, and writers tend to be highly opinionated about what constitutes good or bad writing. Thus over at the Washington Post is a very long list of clichés and stale phrases that are now verboten due to overuse: "The Outlook List of Things We Do Not Say."

Here's a sample:

Upon deeper reflection (why not reflect deeply from the start?)

Begs the question (unless used properly — and so rarely used properly that it's not worth the trouble)

Suffice it to say (if it suffices, then just say it)

Palpable sense of relief (unless you can truly touch it)

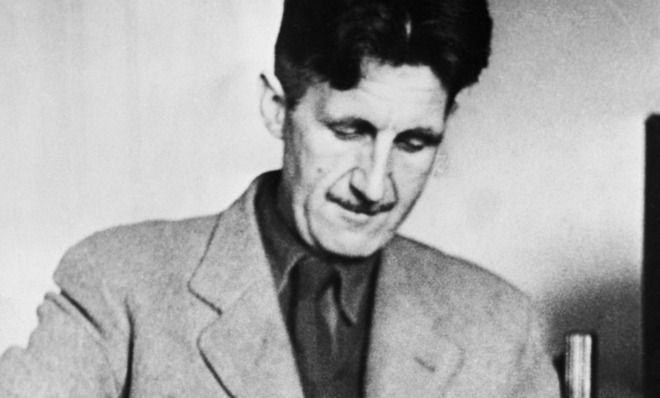

Orwellian (unless discussing George Orwell)

Gladwellian (never)

Inflection point

Byzantine rules (unless referring to the empire in the Middle Ages)

A modest proposal (this was written once, very well, and has been written terribly ever since) [Washington Post]

Some of those are pretty funny — and it is mostly a joke, I understand. But when writers put together a list of ostensibly objective rules for writing, it's common to smuggle in what are actually matters of taste.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Take a word like "Gladwellian." Now, I won't defend Malcolm Gladwell, not when he does things like this. But "Gladwellian" is an adjective that could be extremely useful. Why? Because Gladwell is very famous, and has a very distinctive style! I imagine the outright prohibition comes from imagining the TED talk set writing about "Gladwellian genius" and nodding knowingly to each other. But one could also say "dig this Gladwellian sophistry" and capture an entire sensibility with great efficiency: namely, sophistry featuring great writing, sloppy research, exaggerated claims, and lots of contrarian questions.

Now, maybe you still don't like that, and that's fine. I wouldn't use it myself, to be honest. But let's not pretend that nixing "Gladwellian" wholesale is anything more than a function of taste.

On a deeper level, a list like this also illustrates a common writerly error: the idea that good writing has much at all to do with good ideas. In fact, the opposite is often the case: good writing can make bad, even dangerous, ideas more convincing.

The argument against clichés and hackneyed prose in general, most famously articulated by George Orwell in his famous essay "Politics and the English Language," goes something like this: Thinking is hard, and putting one's thoughts clearly into words is harder. Clichés allow people to short-circuit this process, resulting in "phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated henhouse."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Fair enough. But while I quite like the man, I think it would be the height of disrespect to Orwell's legacy for his work to become unquestionable dogma. Indeed, I think a big part of Orwell's theory of how language operates (developed most fully in 1984) is just wrong.

In the essay, he says, "If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought." In Orwell's world, bad political writing — the kind that teems with cliché, jargon, and cant — is a subspecies of the kind of authoritarian language that seeks to control thought by subverting meaning. And it is surely true that corporate PR flacks and government propagandists constantly churn out deceptive or incoherent copy, with no one better than Orwell at fileting such drivel.

But at least in a free society, their deception doesn't actually work, not even in the medium run. Phrases like "collateral damage" or "enhanced interrogation" fail utterly to veil the reality of civilian casualties and torture, respectively, and are only more horrifying for what they imply about the propagandists who cooked them up. (A similar backlash is happening to new phrases like "signature strikes.")

In other words, corrupt writing is not necessarily capable of corrupting thought. Meanwhile, it's quite easy to convey a crystal-clear thought even if the prose is riddled with clichés. For example: "Upon deeper reflection, House Republicans' last-ditch effort to repeal ObamaCare was motivated by naked partisanship. The connection to the policy itself was tenuous at best."

It's also possible to have excellent, original writing conveying ideas that are completely bananas. As Matt Yglesias said about Notes from Underground: "Dostoevsky is also an illustration of the power of great writing to convey radically unsound or even totally nonsensical ideas." The same could be said of Nietzsche, for example, and many others.

Professional writers are prone to believing that eschewing stale phraseology is the road to clear thought. But I don't think it's so easy.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.