This is what happens when you blow a celebrated theory wide open

The story of Nick Brown, a plucky amateur who dared to question a celebrated psychological finding

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was autumn of 2011. Sitting in a dimly lit London classroom, taking notes from a teacher's slides, Nick Brown could not believe his eyes.

By training a computers man, the then-50-year-old Brit was looking to beef up his people skills, and had enrolled in a part-time course in applied positive psychology at the University of East London. "Evidence-based stuff" is how the field of "positive human functioning" had been explained to him — scientific and rigorous.

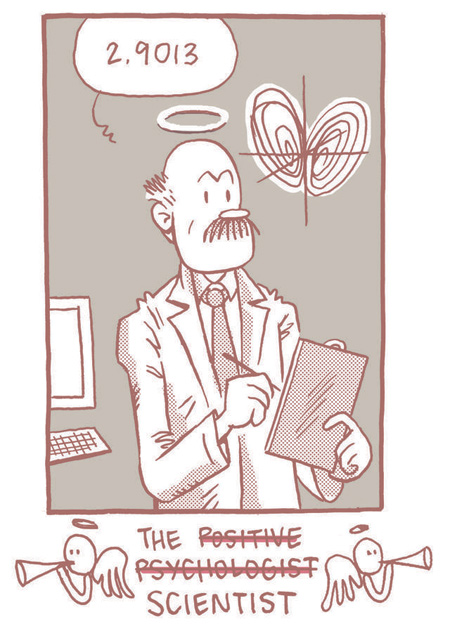

So then what was this? A butterfly graph, the calling card of chaos theory mathematics, purporting to show the tipping point upon which individuals and groups "flourish" or "languish." Not a metaphor, no poetic allusion, but an exact ratio: 2.9013 positive to 1 negative emotions. Cultivate a "positivity ratio" of greater than 2.9-to-1 and sail smoothly through life; fall below it, and sink like a stone.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The theory was well credentialed. Now cited in academic journals over 350 times, it was first put forth in a 2005 paper by Barbara Fredrickson, a luminary of the positive psychology movement, and Marcial Losada, a Chilean management consultant, and published in the American Psychologist, the flagship peer-reviewed journal of the largest organization of psychologists in the U.S.

But Brown smelled bullshit. A universal constant predicting success and fulfillment, failure and discontent? "In what world could this be true?" he wondered.

When class was over, he tapped the shoulder of a schoolmate he knew had a background in natural sciences, but the man only shrugged.

"I just got a bee in my bonnet," Brown says.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

(More from Narratively: Waiting for Zoloft)

Before enrolling in the positive psychology program at the University of East London, Brown had been in a self-described "rut."

The married father of two had graduated from Cambridge University in 1981 with a degree in computer science, and spent most of his career as an IT networks operator at an international organization in Strasbourg, France.

After nearly 20 years in the position, stretched thin between technical duties and managerial headaches, he was looking for something new. So he jumped at the chance to transfer into human resources when it presented itself. The move didn't deliver the change he was expecting, however. Still operating in a large bureaucracy — the same organization, in fact — Brown was now tasked with promoting staff welfare. But he had "little leeway to make decisions," and was constantly signing off on stuff he "thought was just plain wrong." Adding insult to injury, when charged with renewing his company's suppliers list for training and coaching materials, he wound up interacting with "nuts" and "charlatans," people who listed reiki and crystal healing among their interests, or resorted to "hand-waving" when selling their wares.

He was fed up. Coming up on 50, his mother ailing, "the general BS, the constant, not particularly high, but nonstop level of moderate dishonesty," was beginning to wear on him.

Then one day in November 2010, Brown happened to find himself at a Manchester conference attending a talk by popular British psychologist Richard Wiseman, who had written a book called The Luck Factor.

"Basically, the way to be lucky is to just put yourself in situations where good things can happen," Brown remembers, "because more good things will happen to you than bad on any given day, but nothing will happen to you if you just sit indoors."

After the talk, Wiseman signed books. The pile dwindled down and down, and only four books remained when Brown made it near the front of the line. Four people were standing between him and Wiseman.

"I thought, 'Well okay I'm not going to get one,'" he says. "And then I was about two feet from the front, and the woman in front of me, she was one step away from him — had been queuing for 20 minutes — she just decided she didn't want a book anymore and walked off."

"Well there you go," Brown said, greeting Wiseman, "the science of luck."

The two men laughed and got to talking. Brown explained his situation at work. He asked Wiseman where he could find "evidenced-based stuff," science-backed skills he could use to motivate employees and gain the upper hand of the hucksters and quacks hawking Tony Robbins-esque fluff.

The emerging field, Wiseman said, was called positive psychology.

(More from Narratively: Matchmaker for the mentally ill)

As described by the Oxford University Press, positive psychology aims "to study positive human nature, using only the most rigorous scientific tools and theories."

In 1998, then-president of the American Psychological Association Martin Seligman announced the birth of positive psychology, calling it, "a reoriented science that emphasizes the understanding and building of the most positive qualities of an individual: optimism, courage, work ethic, future-mindedness, interpersonal skill, the capacity for pleasure and insight, and social responsibility."

In large part, positive psychology can be defined by what it is not — the study of mental illness (rather, it aims to preempt it) — and in contrast to what came before it — a branch of the social sciences called humanistic psychology that focuses on "growth-oriented" aspects of human nature, but which some in positive psychology criticize as not being adequately scientific.

A typical positive psychology exercise, as described by Seligman, the movement's most visible figure, in his popular 2011 book Flourish, goes like so:

"Every night for the next week, set aside ten minutes before you go to sleep. Write down three things that went well today and why they went well."

The "What Went Well" or "Three Blessings" exercise, which is known in positive psychology as a "positive intervention," comes as part of a package of treatments collectively called positive psychotherapy. And in a study of people with severe depression, Seligman found that positive psychotherapy relieved, "depressive symptoms on all outcome measures better than treatment as usual and better than drugs."

Similar findings have afforded positive psychology a level of public credibility that few other psychological subfields enjoy. Centers and academic programs have sprouted up across the world, the most influential of them being Seligman's own one-year, $45,000 Master of Applied Positive Psychology program at the University of Pennsylvania.

In 2002, with a $2.8 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education, the Penn Resiliency Program (part of the University of Pennsylvania's Positive Psychology Center) began a four-year study of positive psychology's effects on ninth-graders at a high school outside of Philadelphia. Six years later, in 2008, Seligman entered into a far-reaching collaboration with the U.S. Army, resulting in a $125 million government-funded "Army-wide" program known as Comprehensive Soldier Fitness (CSF).

Guest-editing a January 2011 special edition of the American Psychologist that was dedicated to the program, Seligman wrote, along with two military personnel, that CSF's goal is to, "increase the number of soldiers who derive meaning and personal growth from their combat experience," and "to decrease the number of soldiers who develop stress pathologies."

(More from Narratively: Discourse with the dead)

Recently, however, it has been reported that CSF has done little to reduce PTSD. Nevertheless, the government is expanding the $50-million-per-year program.

One of the authors who contributed to the American Psychologist's special edition on Comprehensive Soldier Fitness was Barbara Fredrickson. Co-writing "Emotional Fitness and the Movement of Affective Science from Lab to Field," she cited her 2005 work on the "critical positivity ratio."

Fredrickson is best known for her "broaden-and-build" theory, which posits that the cultivation of positive emotions promotes greater and greater wellbeing. She is considered a rock star of the positive psychology movement, once having been praised by Seligman as its "laboratory genius." Over the course of her career, according to her curriculum vitae, she has received $240,000 in awards and fellowships and over $9 million in grant funding.

Where the concept of a ratio of positive to negative emotions dates back to the 1950s, the specific origin of the critical positivity ratio took place in 2003, writes Fredrickson in her general readership book Positivity: Top-Notch Research Reveals the 3-to-1 Ratio That Will Change Your Life.

A Chilean business-consultant named Marcial Losada, "who had begun to dabble in what had become his passion: mathematical modeling of group behavior," sent her an out-of-the-blue email. Appealing to research he performed in the 1990s that coded the language of 60 business teams for positive and negative affect, Losada said he had "developed a mathematical model — based on nonlinear dynamics — of (Fredrickson's) broaden-and-build theory."

Two independent tests by Fredrickson studying the emotional ratios of individuals seemed to confirm Losada's findings. In 2005, the two unveiled the critical positive ratio in an American Psychologist paper titled "Positive Affect and the Complex Dynamics of Human Flourishing."

The theory was bolder than bold: Mankind, whether working alone or in groups, is governed by a mathematical tipping point, one specified by a ratio of 2.9013 positive to 1 negative emotions. When the tipping point is crested, a kind of positive emotional chaos ensues — "that flapping of the butterfly's wing," as Fredrickson puts it — resulting in human "flourishing." When it is not met (or if a limit of 11.6346 positive emotions is exceeded, as there is a limit to positivity), everything comes grinding to a halt, or locks into stereotyped patterns like water freezing into ice.

In Positivity, Fredrickson writes that it is possible to promote positive emotions and decrease negative ones. The critical positivity ratio, then, represented a stark dividing line — the difference between a bummer of a life and a blissful one. Feel good about twelve things in your day and bad only about four, and by the laws of the ratio you'll be happy. Knock just one of the good emotions out, however, and you won't. So get that extra cookie and talk with someone you love, and push yourself over the mathematical hump.

"Our discovery of the critical 2.9 positivity ratio," Fredrickson and Losada wrote, "may represent a breakthrough."

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric car

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric carThe Week Recommends The family-friendly vehicle has ‘plush seats’ and generous space