How to train your shark

Sharks are not the mindless eating machines Hollywood would have us believe

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sharks are monsters, this we know. They prowl the Earth's oceans killing indiscriminately, with dead eyes and the compassion of Charybdis. So why, then, when I stand in front of the Ocean Exhibit at the Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium, is it not a constant blood bath?

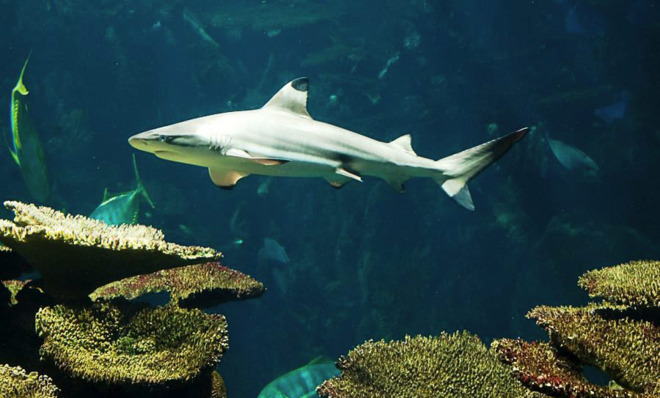

The 100,000-gallon exhibit is two stories tall and teeming with 50 different species of life. Eight-hundred-pound Queensland groupers lumber through the tank with silent stares. A leopard-print laced moray eel slinks along the rocks on the wall. Stingrays, snapper, and five species of tang — blue, yellow, sailfin, unicorn, and regal — flit to and fro, while schools of smaller fish break and reform as three blacktip reef sharks rip through the water like a squadron of fighter jets.

These sharks are six-and-a-half-foot apex predators that regularly snack on sea snakes, reef fish, and ocean invertebrates. And yet the tank remains as placid as Pride Rock on Simba's nameday. What gives?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One of the zoo's aquarists, Ariella Wiener, explained the peace accord easily enough: They train the blacktips not to eat the other fish.

"Sharks have such a bad reputation as being these really aggressive, super-dominant, bloodthirsty creatures," said Wiener. "It's really pretty far removed from the truth."

Three times a week, Wiener engages the sharks of the Ocean Exhibit in training sessions. Each session starts when she lowers a red triangle into the water using a long pole. In an instant, the water beneath her begins to churn with blacktips. One by one, she slips sardines laced with vitamins into the water for each shark. Because this is her assigned exhibit, Wiener knows each animal intimately and uses the opportunity to check them for signs of sickness, injury, or stress. Every pockmark and scab gets documented.

When the blacktips start to lose interest, Wiener stops feeding. The tank is a massive, closed-loop system, and every uneaten morsel degrades water quality. Besides, the zebra sharks are up next, so Wiener trades the pole with a red triangle for one with a yellow circle and moves into position above the opposite side of the tank.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All these details are important for the kind of repetitive operant conditioning the zoo practices. The sharks learn to associate certain actions with rewards. Just as your dog has learned which cupboard you keep the treats in, the blacktips and zebra sharks respond to the aquarist's signals because they know compliance will earn them bites of mackerel, pollock, and squid. Sure, the blacktips could nab a fish or two from the exhibit — and Wiener admits that it might happen on rare occasions — but why waste the effort when you know that red triangle's coming?

And the benefits of training go beyond mealtime. For one, the back and forth keeps the animals stimulated. Otherwise, a bored blacktip might be liable to lash out at the other fishies. And if any of the big fish get sick or injured, or require special attention for some other reason, the staff can use the conditioning to access them with ease. "In an exhibit as big as this one," Wiener explained, "it would be really stressful on the fish, and a really inefficient use of time, to have to jump in there and try to force the fish to come up to the surface."

I should also note that there are circumstances that necessitate humans dropping into the shark tank. You can't imagine the vigilance required to keep a 100,000-gallon saltwater tank clean and thriving. In addition to three stories worth of filtration systems and protein scrubbers the size of silos — the contents of which Wiener compared to the Bog of Eternal Stench — the aquarium requires good ol' fashioned, hands-on scrubbing. And to do that, you need divers.

Wiener is also the coordinator for the zoo's volunteer dive program, which allows divers to get scuba hours in exchange for a little elbow grease. (As you can imagine, there aren't many places to get good diving experience in Pittsburgh.) Obviously, volunteer divers have to go through extensive safety training before they're allowed anywhere near the animals, but I raise the point so that you understand how seriously mellow sharks can be. The PPG Aquarium also has a large exhibit full of sand tiger sharks that are nine feet long, and have mouths so full of teeth it looks like they're falling out. And volunteers are in there with the hydro-scrubbers basically every damn day of the summer.

Sharks aren't the only animals that respond to training. The massive, cattle-sized Queensland groupers I mentioned earlier come up for food whenever Wiener waves her arm over the water's surface. The titans are named Eugene and Brutus and when they hit the surface it sounds like a balloon popping.

The zoo's tigers are also trained to present a hip whenever they get a treat by a certain fence, which allows the vets to administer medicine. And when one of the polar bears started acting strange and not eating, the keepers were able to find out what was wrong simply by prompting the bear to open up and say "ah" — a behavior the animal had learned through months of repetition. The culprit? A mangled molar in need of dental work.

Clearly, there's a difference between your Pomeranian and a blacktip reef shark, and none of this should be taken to say that wild animals are somehow cuddly. They are not. But the work Wiener does with the blacktip reef sharks also shows that these creatures do not spend their days killing on autopilot.

"There are over 400 species of sharks," said Wiener. "They have such varied diets and roles to play in the ecosystem, but all of them are important."

Nearly a quarter of all shark species are in danger of extinction. Even now, the Australian government is encouraging fisherman to catch and kill sharks of a certain length in an attempt to protect swimmers — despite scientific evidence that shows shark culls have little to no effect on human safety. It doesn't help that every time a shark brushes up against a surfer the media starts pumping out headlines advertising a "shark attack".

In spite of it all, sharks were responsible for just two fatalities in the U.S. last year. For perspective, 32 people died after being attacked by dogs.

Jason Bittel serves up science for picky eaters on his website, BittelMeThis.com. He writes frequently for Slate and OnEarth. And he's probably suffering from poison ivy as you read this.