The forgotten streams of New York

An underground explorer discovers his city's lost lifeblood

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On a cold day in the Bronx last winter, I descend underground and splash into the freezing water of Tibbetts Brook. Tearing the tough rubber of my hip-high wader boots, I half-climb, half-fall along the stone wall where excess pond water flows into this dark tunnel. Immediately, my soaked legs begin to go numb from the cold. I'm excited nonetheless: This waterway that I had seen only on century-old maps now seems fully real, glinting in the light of my headlamp as it swirls through the eight-foot-wide brick tunnel.

While few modern-day New Yorkers have heard of Tibbetts Brook, it is one of the city's great lost streams — one of dozens of trickling waterways, both named and anonymous, that were once the lifeblood of a burgeoning metropolis. As New York grew in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries to become the world's greatest port and its most famous city, it depended not only on the dominant Hudson River with its undrinkable saline water, but also on freshwater streams like Tibbetts, the Minetta Brook in Manhattan, Sunswick Creek in Queens, and the Wallabout Brook in Brooklyn.

(More from Narratively: NYC waiters spill their secrets)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the early days of the towns and villages that would eventually merge into New York City, it was often these smaller watercourses that were the most vital; manageable streams provided not only transportation routes, but also water power for grain mills and sawmills, a bounty of fish, and drinking water. They were also a ready source for water-intensive industries ranging from the breweries of Bushwick to the tanneries upstate. In many cases — like Yonkers, for instance — these smaller watercourses were the original reason for a settlement's existence in the first place.

Over time, though, many of these small streams became inadequate for the growing populations that had sprouted up on their banks, and instead of supplying freshwater they became polluted nuisances. As modern industrialization developed in the nineteenth century, railroad lines eclipsed waterways as transportation routes, and first steam and then electrical power replaced the water power of earlier days. With further development came the burial of Tibbetts Brook, and many of the other streams. In some cases, putting them underground was merely a way to create more buildable land above. In others, the streams that once supplied drinking water or fish were converted into sewers and drains. Today, the lineage of many of the major sewer lines in New York City can be traced back to streams and rivers that flowed unfettered for centuries and even millennia before the city matured around them. Today, their past is all but forgotten.

* * *

After an interminable few minutes of wading, the cold biting into my feet, the water and I both emerge into a new tunnel underneath one of the major roads in the Bronx. It's a beautiful double-arched brick channel constructed in 1899, with two parallel channels about three meters high and four wide. Inside this tunnel everything is different. Suddenly, the air is humid, and the water is warm, though it's also become brown, opaque, and fetid, only slightly diluted by the Tibbetts' flow. I'm now in the sewer, and I try hard not to think about what is actually sloshing around inside my boots; I'm tracing history — cleaning up can wait.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

(More from Narratively: A candy collector and his 10,000 wrappers)

You might say my exploration begins with a landowner and mayor of New York named Jacobus Van Cortlandt, who dammed Tibbetts Brook in 1699. There, in a section of northeastern Bronx where his namesake park would be realized two hundred years later, Van Cortlandt installed both a sawmill and a gristmill, and they continued to operate until 1889, when the city purchased the land for its park. Van Cortlandt's old millpond became a decorative pond.

Downstream of the pond, Tibbetts Brook was re-channeled into an underground tunnel, eventually merging into a massive, double-arched brick sewer beneath Broadway that is the main sewer line for much of the northern Bronx. This sewer tunnel actually extends the brook's reach much farther south than its original outlet, carrying it into the Spuyten Duyvil channel and then on through twentieth-century interceptor sewers to the Hunts Point treatment plant.

The old course of the brook is still memorialized above ground by the tree-lined Tibbett Avenue, home to both Tudors and drab apartment complexes. The street dead-ends at approximately the point where the original Tibbetts Brook flowed into the old Spuyten Duyvil Creek, after completing its journey through a series of marshy meadows.

(More from Narratively: Crazy tales from the subway tunnels)

New York City's first underground sewer, which ran beneath Canal Street, is a remnant of water sources that were once fundamental to New York City's origins.

Originally a meandering and marshy waterway, the Canal Street sewer was bookended by the Hudson River, with its saline water and its four-and-a-half-foot tides, and a deep pond fed by underground springs. The overflow from the spring-fed pond flowed slowly westward into the Hudson along this route, forming a wetland that extended deep into what is now SoHo and TriBeCa.

When the tide was high in the Hudson, the waterway was deep enough to float a canoe. Native Americans living in the area brought catches of oysters in through this route, and over the years the discarded oyster shells formed a hill beside what would the Europeans would call the "Collect Pond."

Cattle that set out in the surrounding fields were sometimes lost in the "pestilential quagmires" around them. One nineteenth-century writer told of a man, lost in the dark, who drowned in deep water at what is now the intersection of Grand and Greene Streets — smack in the heart of SoHo.

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

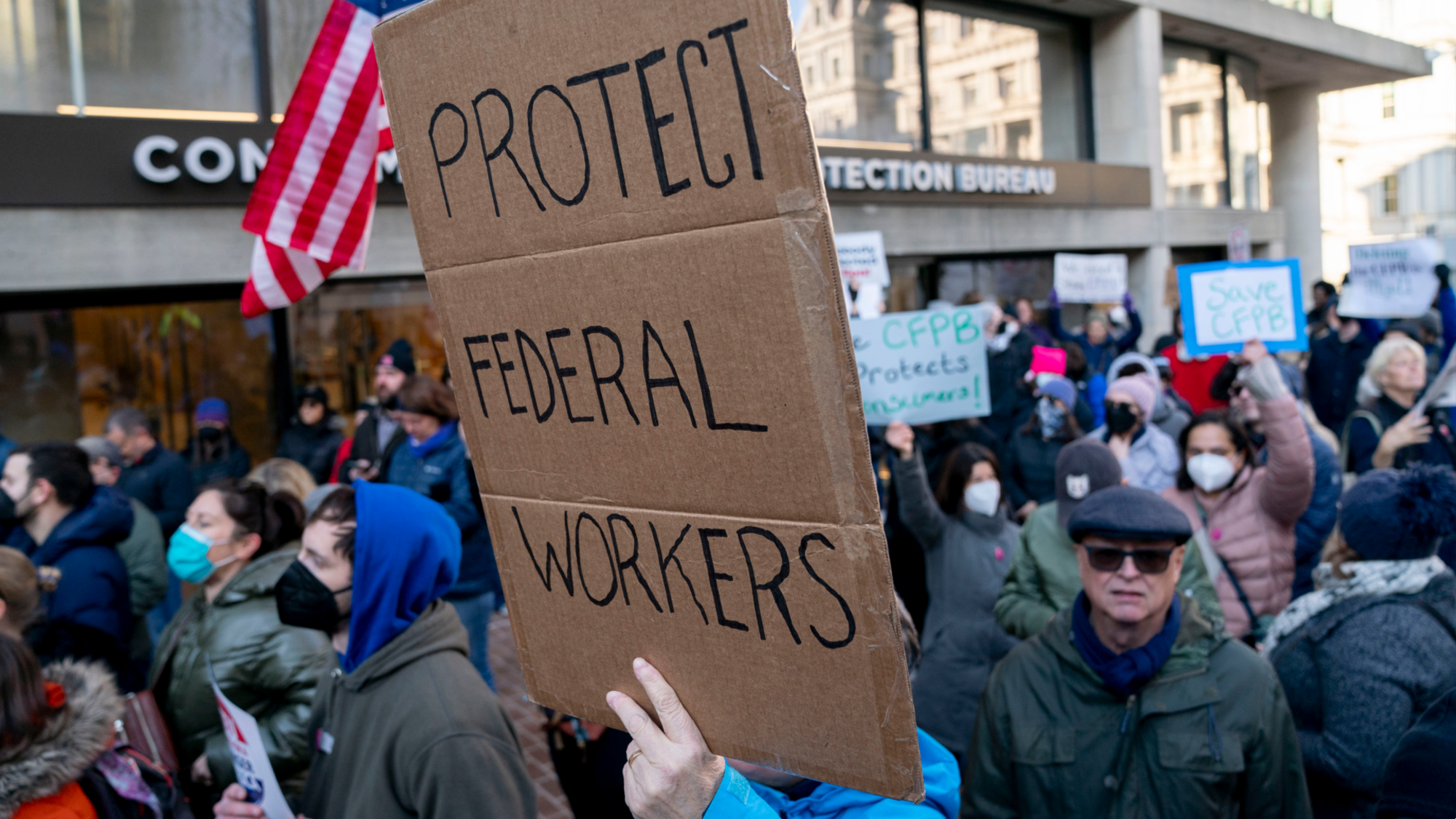

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firings

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firingsSpeed Read The rule strips longstanding job protections from federal workers

-

What to watch out for at the Winter Olympics

What to watch out for at the Winter OlympicsThe Explainer Family dynasties, Ice agents and unlikely heroes are expected at the tournament

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland