9 things you didn't know were named after people

You didn't want to face off against the artillery of General Henry Shrapnel

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

1. Mesmerize

Franz Mesmer wasn't a cheap vaudeville hypnotist. He was a doctor in the 18th century. And…he was sort of a quack. But just about everyone was a quack in those days; medical successes were measured by the least amount of people killed. So when Mesmer began to advocate a new healing technique he'd discovered, the use of what he called, "animal magnetism," people were open-minded. He believed that simply by sitting with a patient, looking in their eyes, and touching them in various medically appropriate places, he could cure them through natural magnetic force. The medical community didn't buy it, but the public liked it. In the mid-1800s, long after Mesmer's death, the term "mesmerize" had morphed into a synonym for hypnosis, and then later gained an even more fantastical definition, as "mesmerizing" became a popular stage act for magicians and vaudevillians.

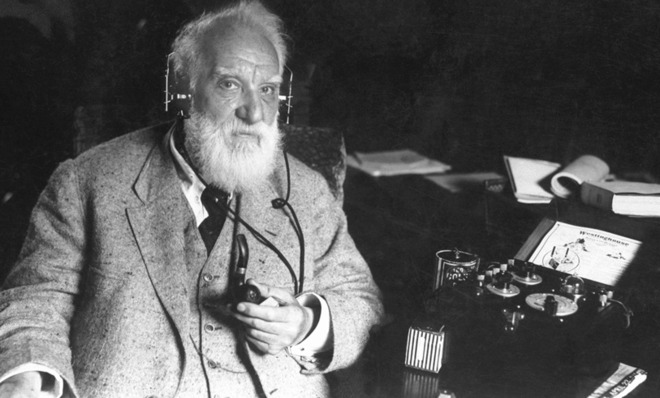

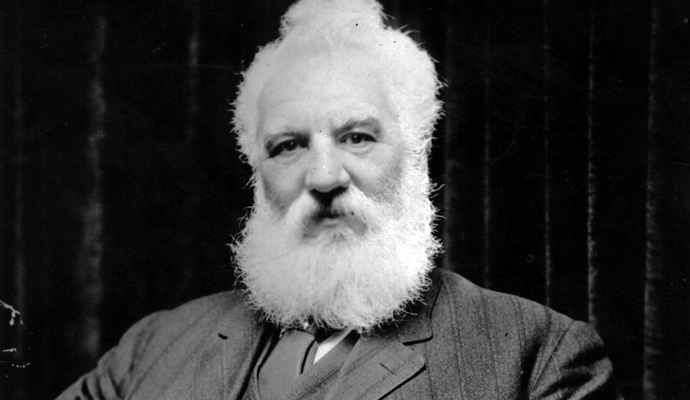

2. Decibel

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Alexander Graham Bell, man. He's everywhere. Since he revolutionized how sound is transmitted and recorded, it seems fitting that his name should be used to help measure it. A "decibel" is one-tenth (deci) of a little-used unit of measurement called a "bel," named, of course, after the Great One himself.

3. Galvanize

Luigi Galvani's original work had nothing to do with covering metal with zinc to prevent rusting. It was actually much cooler. Galvani was an 18th century Italian scientist who electrocuted dead frogs to see their muscles twitch, which was pretty amazing at the time. So "to galvanize" originally meant to cause something to jolt into action, as if shocked by electricity. Then it meant shocked by electricity. Which is the base of electroplating, which is an earlier iteration of the chemical process we know as galvanization. See? It all checks out.

4. Fuchsia

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Leonhart Fuchs didn't discover the fuchsia genus. He liked plants, though. He wrote a book called an herbal in 1542 about using plants as medication. His book was arguably the most highly regarded herbal of the Renaissance. So in the late 1600s, when French Botanist Charles Plumier discovered a new kind of flower in the Caribbean, he named it in honor of what must been have the botany version of Elvis, Fuchs. The subsequent color, which interestingly is interchangeable with the one called "magenta," was coined in 1859.

5. Maverick

The word makes you think of fighter planes and shoot outs and police chiefs shouting, "You're loose cannon!" over their desks at someone. But no. A maverick is a cow. A cow with no brand burned onto its hide, but still, just a cow. The name comes from Samuel Maverick, who was a lawyer, land baron, and politician in 19th century Texas. Though he was a piece of work himself, the term came into our language through his cows. He said he didn't want to hurt them with branding. Other people thought he just didn't care all that much about cattle ranching. Still others thought he was using that Maverick guile, employing a strategy that allowed him to claim any unbranded cattle he found as his own.

6. Saxophone

Adolphe Sax invented and improved on a lot of horns during the 19th century. But you know him for the saxophone, which in itself represents an entire family of instruments. He wanted to make an instrument that blew like a horn but could be manipulated with the agility of a woodwind. Other designers attacked his patents and, despite inventing an instrument that altered modern music as we know it, he was declared bankrupt twice before his death in 1894.

7. Bakelite

If there is even a bit of antique-lover in you, you know how giddy the word "Bakelite" can make a collector feel. Bakelite was the first incarnation of synthetic plastic as we know it. It was heavy, rich-textured, held a vibrant color, and as a bonus, was non-flammable. It was a revolution in the 1920's, used for everything from jewelry to pipe stems. Though marketing couldn't have come up with a more delicious name than "Bakelite" for its product, it was named for its inventor, Leo Baekeland. Baekeland was a brilliant chemist who patented more than 55 inventions and processes in his life. He died shortly after his son pressured him into retirement, after selling Bakelite to Union Carbide.

8. Macadamia

Macadamia nuts come from Australia, and the indigenous people there were eating them long before western botanists ever heard of them. They're named for a famous 19th century chemist/politician John Macadam, but he didn't discover them or introduce them to the west. His friend Ferdinand Von Mueller named them after him. That was after, as the story goes, Mueller sent the plant to be studied at the Botanical Gardens in Brisbane. The director told a student to crack open the new nut for germination. The student ate a few and said they were delicious. After waiting to see whether or not the young man would die in the following days, the director tasted a few himself and declared Macadamias the finest nut to have ever existed.

9. Shrapnel

Shrapnel, metal debris that flies at lethal speed from explosions, can be useful in warfare even when it's not lethal. This is because shrapnel wounds more often than it kills, and it takes two solders to drag one wounded soldier off the battlefield. That might have been what Major General Henry Shrapnel had in mind when he began designing a new kind of bomb in 1784, what he called "spherical case" ammunition. It was a cannonball that contained lead shot, turning a cannon fire into an enormous shotgun blast. Forms of the shrapnel bomb (called an "anti-personnel" bomb) were used clear into WWI. The name eventually came to mean any fragmentation resulting from an explosion.

Therese O'Neill lives in Oregon and writes for The Atlantic, Mental Floss, Jezebel, and more. She is the author of New York Times bestseller Unmentionable: The Victorian Ladies Guide to Sex, Marriage and Manners. Meet her at writerthereseoneill.com.