The tricky science of trying to tickle yourself

Spoiler alert: You probably can't

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's darn near impossible to tickle yourself. Kids know this. Adults who act like kids know this. And so do the creators of certain Sesame Street toys that tend to inspire fist-fights between strangers every year around the holidays.

The mechanics behind the non-phenomenon of self-tickling are pretty straightforward: Your subconscious mind is always one step ahead of you. Your "unexpected" touch, no matter how cleverly you disguise it, is almost always expected — and that's largely a good thing. Here's how Sara-Jayne Blakemore, a researcher at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London, explained it to Scientific American in 2007:

…the cerebellum can predict sensations when your own movement causes them but not when someone else does. When you try to tickle yourself, the cerebellum predicts the sensation and this prediction is used to cancel the response of other brain areas to the tickle.

Two brain regions are involved in processing how tickling feels. The somatosensory cortex processes touch and the anterior cingulate cortex processes pleasant information. We found that both these regions are less active during self-tickling than they are during tickling performed by someone else, which helps to explains why it doesn't feel tickly and pleasant when you tickle yourself. [Scientific American]

The brain is programmed to anticipate unimportant sensations, like your rear against a comfy chair or the socks on your feet. It saves those valuable synapses for the weird and unexpected, like when there's a poisonous spider crawling down the back of your shirt.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Our utter imperviousness to the self-tickle can even conquer technology intended to camouflage it, to an extent. In a recent interview with NPR, professor Jakob Hohwy, a philosophy researcher at Monash University in Australia, outlines a bizarre and wonderfully elaborate experiment designed to trick the brain.

HOST: In his tickling experiment, Hohwy used his own version of the rubber hand trick. He made his subjects wear a pair of video goggles hooked up to a camera on another person's head. And with good old fashioned synchrony, he got them to feel, as if they were actually the person sitting across the table. And in that moment he had them try to tickle their palm.

HOHWY: And then we ask, how ticklish is it? And it turns out that when they do it themselves, they still can't tickle themselves. [NPR]

There is, however, a lone exception to the no-tickling rule: Schizophrenics have the notable ability to tickle themselves on demand. One theory, according to Hohwy, is that "people with schizophrenia are relatively poor at predicting what the sensory consequences will be of their own movement." Somewhere between the triangulation of fingers, eyes, and the unconscious mind, the electrical signals beamed back to the brain hit a snag.

In many ways, our silly inability to self-tickle showcases the powerful machinery of the human mind at its most efficient: Your brain is in a constant state of trying to predict what's about to happen next. It's always one step ahead and looking to the future, even if you necessarily aren't.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

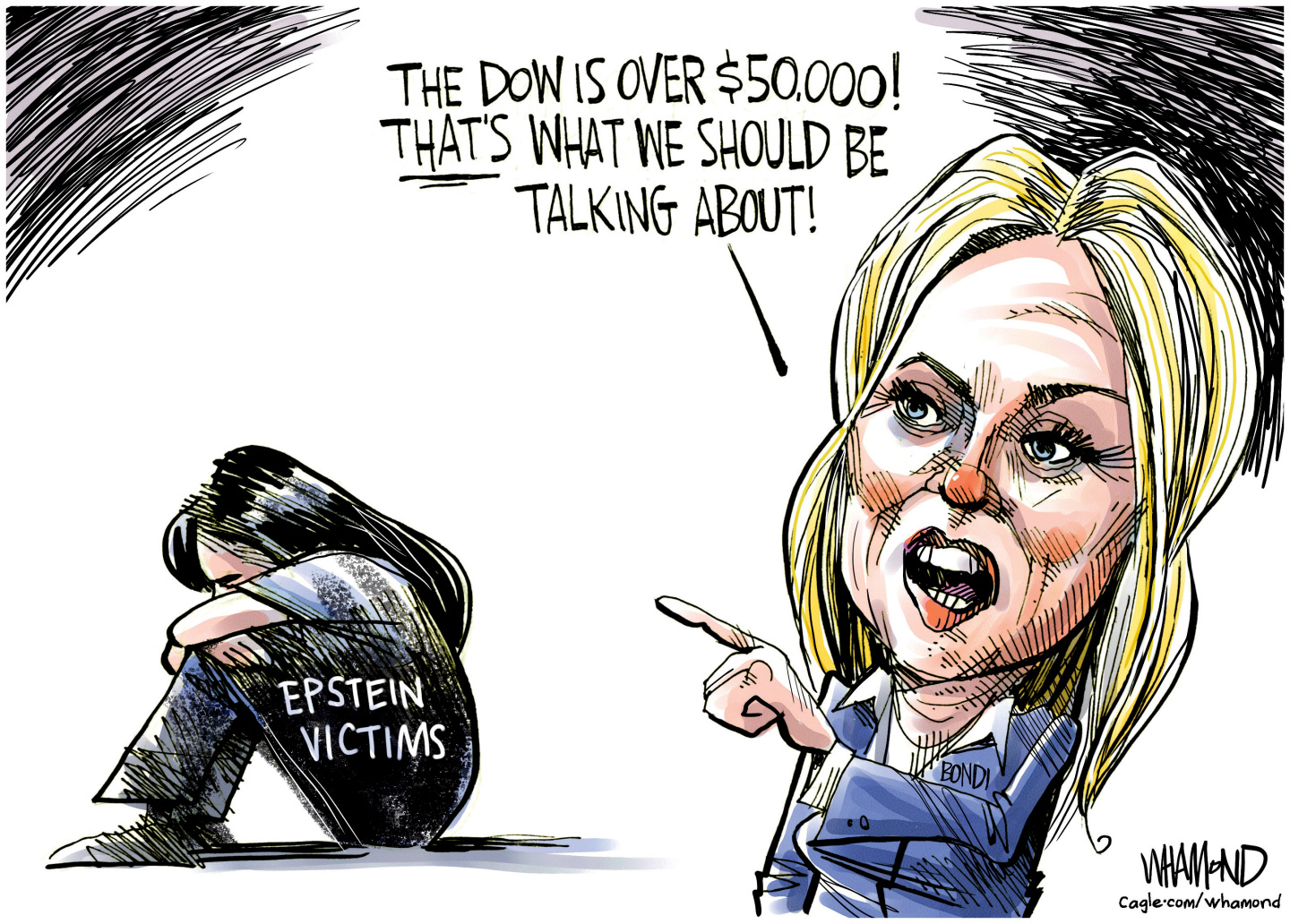

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria