Thanksgivukkah will definitely not ruin Thanksgiving for Jews

Chill out, people

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There are certain things that are bad for the Jews, especially American ones. Son of Sam, Bernie Madoff, and Woody Allen marrying his adopted daughter all fall into this category. But Thanksgiving — or more accurately, this year's Thansgivukkah — is not one of them.

Some folks, however, are apparently dismayed at the overlap of Turkey Day and the Festival of Lights. Allison Benedikt at Slate worries that, as a Jew, Thanksgivvukah will ruin two holidays that are highly enjoyable on their own. For one, she's concerned that her children will start expecting presents every Thanksgiving, equating it with Hanukkah. "I guarantee that every little Jewish boy and girl who gets a gift on Thursday will, going forward, expect gifts the fourth Thursday of November — forever."

This is a pretty weak argument against Thanksgivukkah. For one, if you want to blame anyone for stoking children's inordinate expectations of gifts, blame the behemoth commercial enterprises that rev into holiday gift-giving mode the day after Halloween.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Thanksgivukkah also isn't the first time that Jews have been to the holiday-overlap rodeo. Just because Hanukkah coincides with Christmas some years, doesn't mean Jewish kids expect presents on Christmas every year. Jewish children continue going to the movies and eating Chinese food on Christmas without major present-wanting meltdowns.

More problematically, Benedikt is concerned that the Hanukkah overlap infuses Thanksgiving with a religious tinge. Thanksgiving is "a food and football holiday," she argues. "In my family, at least, the gratitude is secular. So here comes Hanukkah to gum up the works."

I could understand this fear a bit more if Hanukkah were a deeply religious Jewish holiday. But as practiced in America, it bears all the hallmarks of another famous American holiday: Copious amounts of food and materialistic spending that are in no way required by religion.

In fact, there's a good chance that most American Jews wouldn't celebrate the holiday at all if they didn't live in the good old U.S. of A. It's been well-documented that Hanukkah grew in popularity because post-World War II American Jews wanted to fit into the mainstream suburbs, and found in Hanukkah a holiday to match Christmas.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Compared to the religious and spiritual significance of Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippor, and Passover, Hanukkah is a lightweight. Sure, Hanukkah is a great story about overcoming enemies and acknowledging the small miracle of oil lasting eight days to keep candles burning. But you're not standing before God trembling in your sins, begging Him to seal you in the Book of Life (that happy day belongs to Yom Kippor).

Now, I do appreciate Benedikt's concern about Hanukkah being distinctly Jewish, as opposed to Thanksgiving's general "Americanness." As a parent in an interfaith marriage, she says that she especially loves holidays that don't involve explaining to her children "why mom believes this and dad believes that."

But Thanksgiving hasn't been some pure, singular expression of America for quite some time, if ever. The way Americans celebrate Thanksgiving has been individualized and diversified by different ethnic and religious groups long before Thanksgivukkah was on the calendar.

The 2000 movie What's Cooking? (which you should definitely watch if you haven't already) showcases how four families — Jewish, black, Latino, and Asian — have some very different traditions when it comes to Thanksgiving. And that "sweet and sour braised brisket with cranberry sauce" that Benedikt calls a Thanksgivukkah "abomination" has been on my family's Thanksgiving table some years (minus the sweet and sour part — yuck).

Indeed, one of the things that makes Thanksgiving a great American holiday is that it isn't celebrated in a single, "correct" way.

So breathe easy fellow members of the tribe. Both Thanksgiving and Hanukkah will probably survive Thanksgivukkah.

Emily Shire is chief researcher for The Week magazine. She has written about pop culture, religion, and women and gender issues at publications including Slate, The Forward, and Jewcy.

-

Where to go for the 2027 total solar eclipse

Where to go for the 2027 total solar eclipseThe Week Recommends Look to the skies in Egypt, Spain and Morocco

-

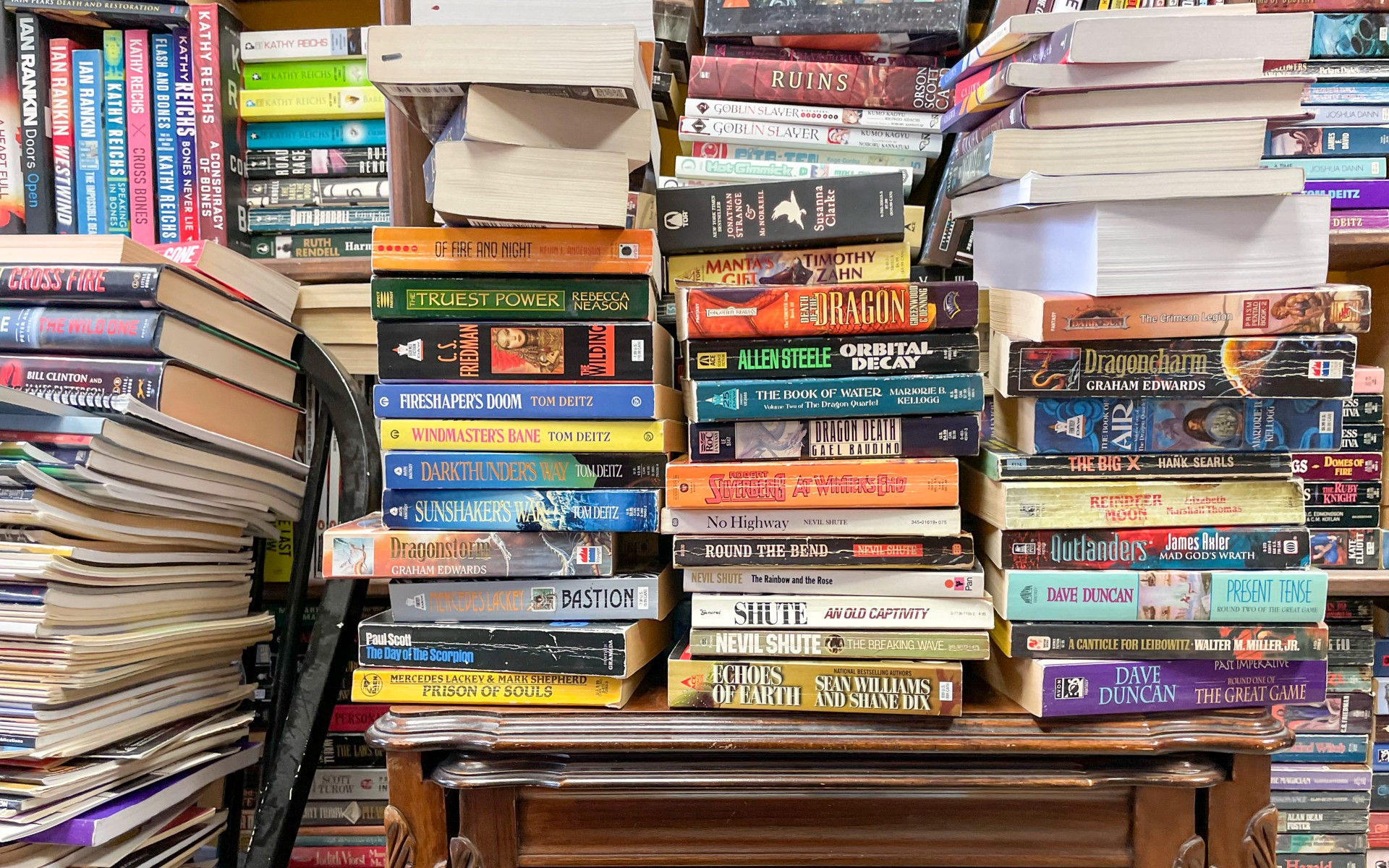

The end of mass-market paperbacks

The end of mass-market paperbacksUnder the Radar The diminutive cheap books are phasing out of existence

-

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more