We need easier money. So why taper?

The Fed is afraid of bubbles. It should focus instead on low inflation and stable employment.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

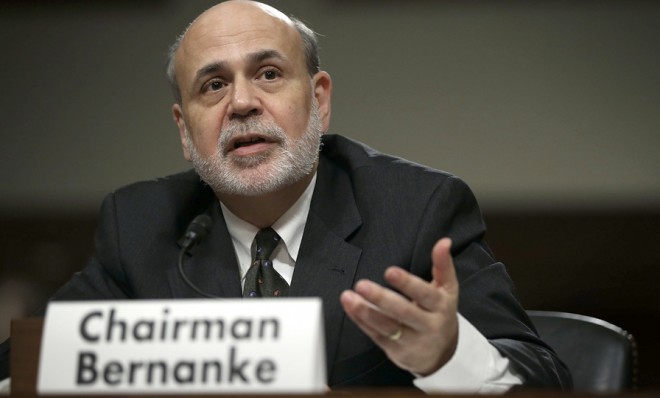

Today, the Federal Reserve is faced with a momentous decision: Should it wind down — or "taper" — its purchases of long-term bonds, or continue its monetary stimulus program of "quantitative easing" at a pace of $85 billion per month? Many experts believe the Fed will decide to gradually taper off the purchases, despite the fact that such a decision would put a damper on the housing market, slow the economic recovery, and depress the stock market.

The goal of this round of quantitative easing (dubbed QE3) was to reduce long-term interest rates in order to boost the economy, especially the depressed housing sector. The Fed said it would adjust the program, adopted late last year, as needed to hit its economic targets. Nevertheless, in June, Ben Bernanke hinted that the Fed might begin scaling back the program in the fall, even though growth this year has been below what the Fed hoped and expected to see. More clues are expected later today.

The effects of the June announcement were felt immediately. Stock prices fell on the news, as investors worried the tapering would slow the recovery. Long-term interest rates rose, presumably because of fears that if the Fed was not buying so many bonds, the Treasury would have to offer higher interest rates to get private investors to finance the budget deficit. Even foreign markets were affected, as U.S. interest rates influence credit conditions elsewhere, especially in the developing world.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some Fed officials have confessed that they're worried about prolonging the period of low interest rates in case economic bubbles once again begin forming in the U.S. However, government officials have never been good at predicting bubbles; if they were, they would be running hedge funds, not working as bureaucrats. In fact, the last time the Fed tightened monetary policy to prevent a bubble was in 1929. That didn't work out too well!

Some also argue that QE3 has done relatively little to boost the economy. That's an understandable concern, as the recovery has been sluggish and lots of the money injected by the Fed has simply piled up in bank "reserves," rather than going out into the economy. But the program has actually been more successful than people realize.

This year, Congress enacted a major austerity program, involving higher payroll taxes, higher incomes taxes, and sharp spending cuts (the sequester.) That would normally slow the economy. However, it's very likely that our QE3 program roughly offset the effects of fiscal austerity, and helped us from slipping into a double-dip recession.

You only need to look to Europe to see the substantial risks of tightening money too soon. In 2011, the European Central Bank tried raising interest rates before a recovery was well-established — Europe slid back into a double-dip recession. Their attempt to "normalize" interest rates actually pushed Europe several years further away from any sort of normal economic situation. It's as if someone who has been seriously ill and bedridden suddenly felt well enough to run a marathon, only to run out of gas and get injured before the finish line. America and Europe otherwise had similar fiscal policies; what kept our economy from great self-harm was that our central bank was more aggressive in monetary stimulus.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If the Fed does decide today to taper it will be a big gamble. It will mean moving away from its normal focus on inflation and employment targets, and instead responding to vague and poorly understood fears of "bubbles." The Fed should continue to focus on its mandate: Stable prices (which they interpret as 2 percent inflation) and full employment.

And that means we actually need easier monetary policy, not tighter.

Scott is a Professor of Economics at Bentley University. His research has been in the field of monetary economics, particularly the role of the gold standard in the Great Depression. Since early 2009, he has been writing posts at TheMoneyIllusion.com.