Why are chemical weapons worse than conventional weapons?

Syria crossed President Obama's "red line" by allegedly using chemical weapons. Why is that any worse than the horrible violence that came before it?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

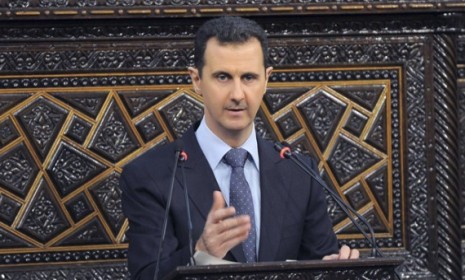

On Tuesday, Secretary of State John Kerry compared Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to Adolf Hitler and Saddam Hussein for using chemical weapons.

"The world decided after World War I, and the horrors of gas in the trenches, and the loss of an entire generation of young people in Europe that we would never again... allow gas to be used in warfare," he told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

The White House says that 1,429 people were killed last month by chemical weapons launched by the Assad regime into the Damascus suburb of Ghouta. Pictures and video reportedly from the scene are heartbreaking. There are infants turned blue and barely breathing, glassy-eyed men foaming at the mouth. The world, certainly, would be better off if weapons like that were never used at all.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The chemical weapon reportedly used by Assad was sarin gas, which, in high doses, can kill within minutes of exposure, first causing convulsions, paralysis, and then, finally, respiratory failure, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But why are they worse than conventional weapons? Or, to be precise, why are they more worth going to war over than conventional weapons? What difference does it make if someone is killed by sarin gas or a missile or bullets from an M16? After all, the total casualties in Syria — said to be more than 100,000 dead — dwarfs the number of those killed by the chemical attack.

"The primary idea is that they are indiscriminate and an inherent threat to civilian populations," Richard Price, a political scientist at the University of British Columbia, told The Washington Post. After World War I, when chemicals weapons like mustard gas and the more deadly chlorine and phosgene were used, there was a fear that rapid advances in aviation technology would lead to devastating attacks on civilian populations.

"They were really the first weapon of mass destruction, but they've never quite lived up to that destructive capacity," Price said, noting that biological and nuclear weapons are much more indiscriminate and deadly.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Since World War I, chemical weapons have been used multiple times — Hitler's gas chambers, Yemen in 1963, the Iran-Iraq war, etc. — but not on the same scale. In a single battle in April 1915, for example, 15,000 Allied soldiers were killed by a German chlorine attack.

In 1925, countries signed a Geneva protocol banning the use of chemical weapons, which was followed decades later by an arms treaty, the Chemical Weapons Convention, in 1992. Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association, told Mother Jones that he found no reason why those restrictions should be lifted or ignored:

Holding the line against further chemical weapons use is in the interests of the United States and international security, because chemical weapons produce horrible, indiscriminate effects, especially against civilians, and because the erosion of the taboo against chemical weapons can lead to further, more significant use of these or other mass destruction weapons in the future. [Mother Jones]

While sarin gas might actually kill you faster than, say, bleeding out from a bullet wound, it has become a "weapon of terror" that we are "hard-wired" to fear because of how unexpectedly and quickly it begins to work, Charles Blair, a senior fellow at the Federation of American Scientists, told the National Post.

"They couldn't smell it, see it coming and 'wham,' next thing you know they're in convulsions, frothing at the mouth and they're dead," he said.

To condemn chemical weapons but use conventional ones, however, is more about political strategy than humanitarian concern, argues Dominic Tierney in The Atlantic:

Strip away the moralistic opposition to chemical weapons and you often find strategic self-interest lying underneath. Powerful countries like the United States cultivate a taboo against using WMD partly because they have a vast advantage in conventional arms. We want to draw stark lines around acceptable and unacceptable kinds of warfare because the terrain that we carve out is strategically favorable. Washington can defeat most enemy states in a few days — unless the adversary uses WMD to level the playing field. [The Atlantic]

Even if chemical weapons aren't worse than, say, the machetes that were used in Rwanda or the guns used by cartels to kill more than 60,000 people in Mexico's drug war, some say banning any form of violence is a good step toward creating a more peaceful world.

"War has been happening for thousands of years; the world has been working to establish norms limiting war for less than a century, a relative blink in our history, and the chemical weapons taboo is just the start," Max Fisher wrote in The Washington Post. "If we let the chemical weapons norm fall back, we’re also setting back any future efforts to constrain war."

Keith Wagstaff is a staff writer at TheWeek.com covering politics and current events. He has previously written for such publications as TIME, Details, VICE, and the Village Voice.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day