Can the Fed wind down its stimulus without hurting the economy?

It's like we're "riding the back of a tiger," says one economist

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As the the five-year anniversary of the 2008 financial crisis approaches, the Federal Reserve is toying with the prospect of phasing out its giant monetary stimulus plan, in which the central bank buys $85 billion worth of treasuries and mortgage-backed securities each month in an effort to hold down interest rates and encourage borrowing.

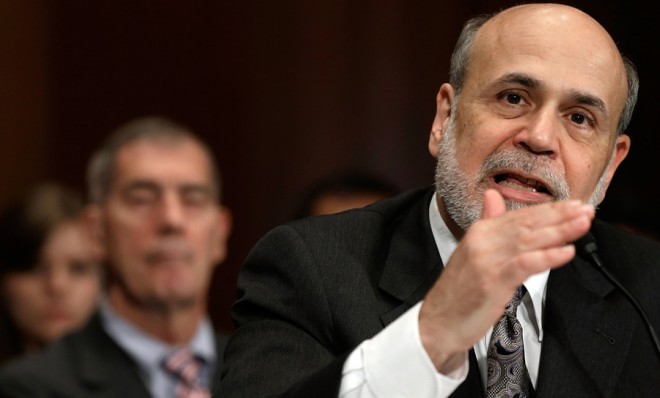

Here's the problem: Every time the Fed mentions the stimulus-slowing possibility, which it calls "tapering," markets go haywire, highlighting how tricky the transition will be. In May, when Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke first floated the idea — with the giant caveat that the economy would need to be in solid shape before tapering began — he set off a short but violent global sell-off.

Pingfan Hong at the World Economic Forum compares the Fed's predicament — it wants to eventually wind down stimulus, but risks a global freak-out by even mentioning it — to "riding the back of a tiger."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"It would be difficult for the Fed and other central banks to 'dismount' from [monetary stimulus] programs without being devoured," he writes. Hong's message is clear: It's relatively easy to begin a fiscal stimulus program, but it's very painful, if not downright dangerous, to stop.

A related concern: Some analysts see the Fed's intervention as a crutch propping up an injured economy rather than a cure that will inevitably help the patient walk again on his own.

"The massive stimulus efforts by global central banks clearly did not provide a permanent cure for the underlying problems, and more problematic, just maintaining the status quo has required increased dosages of stimulus," says Sy Harding at Forbes.

It's like a patient with serious medical conditions being prescribed oxycodone to relieve the pain while a series of time-consuming procedures are planned to fix the condition. If the procedures don't work out, the patient will wake up with the conditions not being cured plus an addiction to oxycodone, withdrawal from which brings additional problems.

That seems to be the situation with the global economic situation. It has required increasing dosages of stimulus to keep the pain only somewhat at bay. And now other problems, like record government debt, require that the dosages be tapered back, even as the economy is unable to maintain the status quo without increasing dosages. [Forbes]

Others — including some at the Fed — think that it's about time to wind down the stimulus, despite the risks involved. "Inflation hawks at the Fed worry the sharp expansion in bank reserves could lead to future inflation, even if there are no signs at all of any imminent price pressures," say Kristen Hays and Francesca Landini at Reuters.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Charles Plosser, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, supports such a plan. "The first step is to wind down our asset purchases by the end of the year in a gradual and predictable manner," he said. "I see little if any benefit from these purchases, and growing costs."

Carmel Lobello is the business editor at TheWeek.com. Previously, she was an editor at DeathandTaxesMag.com.

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more