INTERVIEW: The White Queen writer Philippa Gregory

"This is the family before the Tudors, and I think they're just as interesting. It's not a history documentary. It's entertainment."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The White Queen, which makes its United States debut on Starz this weekend, is a historical drama that offers an unconventional perspective on England's War of the Roses by focusing on three women: Elizabeth Woodville, Margaret Beaufort, and Anne Neville, who each vied for power during the era. It may not feature any dragons, but The White Queen offers a vision of the real-life events that's as packed with backdoor deals and backstabbing as Game of Thrones. "Men go to battle," reads the show's tagline. "Women wage war."

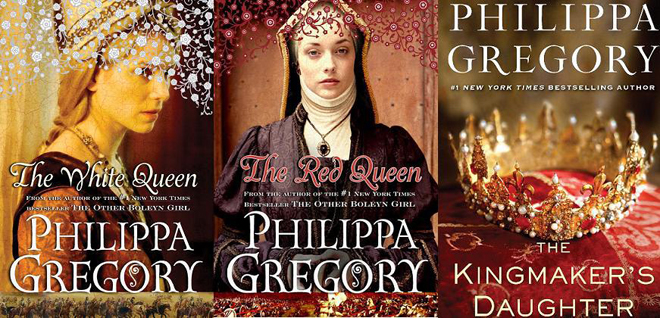

Though it's a drama based on history, The White Queen's unique narrative springs directly from the work of a single woman: Philippa Gregory, a writer and historian who has built her career on historical fiction. Though several of her novels have been adapted as miniseries, TV movies, and theatrical features — including The Other Boleyn Girl, which starred Natalie Portman and Scarlett Johansson — The White Queen is the first time her work has been adapted as a full-blown TV series.

The White Queen has been attacked by some critics in the U.K. as ahistorical. Gregory says they're missing the point: "What [BBC One and Starz] wanted was not a historical series based on the documents from the War of the Roses. They wanted my take on it, so that's what they got." (Gregory also hosted a documentary called The Real White Queen and Her Rivals explaining the unvarnished history behind her series.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I recently sat down with Gregory to discuss how her novels were adapted for The White Queen, how she walks the line between entertainment and historical accuracy, and what historians of the future might write about the people of today. Read our (slightly edited) conversation here:

So many of your stories have been adapted for TV and film, and you've been writing novels even as The White Queen has gone into production. Have these experiences affected the way you write?

Not if you're going to write a good novel. All you have to do if you're going to write a good novel is write a good novel. If you think about anything else, you'll drive yourself crazy. The process of writing the novel is quite absorbing and difficult enough without dreaming about a television series. That came later. That was luck. You know, The White Queen is about 150,000 words. It took about two years to research and write, and the TV series is three novels, so you're talk about a big, big body of work you're trying to get into. We have the luxury of 10 hours, which is enormous compared to what you'd have for a film. But inevitably, novels are much more complex, multilayered… multidimensional, really.

What are the differences between working on a feature film like The Other Boleyn Girl and a TV series like The White Queen?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I think the more money there is in it, the worse it is for the storytelling process. But that's because my view of the storytelling process is very idiosyncratic. The reason I write novels is because I want there to be only one voice in the process. Scripts are much more collaborative. On this production, I think we had four writers altogether, plus me script editing and giving notes. That's a lot of people to tell a story.

The White Queen's characters may be based on historical figures, but you've had to invent so much about them. How did you find the right actors to pull that balance off?

Some parts were very hard to cast. We went round and round and round. I suppose the character of Elizabeth Woodville, the White Queen, was one of the most difficult to cast. We couldn't get agreement on her amongst the producers until the night before the read-through. [Rebecca Ferguson] was literally cast after midnight, and she was in hair and makeup at six the next morning. That was very difficult. And I didn't agree with that; I thought it was absolutely easy. I loved her the moment I first saw her, and was very, very clear from the beginning that I thought she was the one for us. But sometimes people see characters in different ways. I think I tended to see quite a lot of the male parts I had imagined as being broader, and rougher, and more testosterone-driven than the modern actors. But that's partly the fashion that there is for how men look now; in the medieval world you would have to be pretty broad and mean to survive as long as some of these men did.

How do you navigate the line between staying historically accurate and telling the most compelling story?

Well, everybody has their own rules. My own rule is that if there is an established historical fact, you include it, and make it the basis for your story. When there's a great big gap in the story, I go for what I judge to be the most likely explanation. When we simply don't know… Then, I aim for the most likely explanation if we know, in a sense, the start and the end of this gap. Sometimes you're writing a story in which you're trying, in a sense, to be true to the characters that you perceive. For instance, I tend to think of Henry VII — and indeed, his son Henry VIII — as men who started off as pretty well-intentioned, but drifted toward paranoia — and in the case of Henry VIII, of outright madness. Now, that's my take on him. You could find someone who doesn't see that at all. But looking at the facts of his life, that's how I read him. It's a personal view. It's always got to be a personal view.

In the first episode of The White Queen, Jacquetta and Elizabeth use a kind of witchcraft — and it seems to work. How do you justify something like that in a historical drama?

The material that I quote, about [the Woodville women] being related to the Water Goddess Melusina — that's historically in the record. You may or may not believe it, but there it is in the record. So you've got this really profound metaphor for otherworldliness, which goes through their family tree. In the medieval world, you had very superstitious, very religious, very credulous people who had no explanation for phenomena which were terribly dangerous and disturbing. They didn't know what caused thunderstorms or miscarriage or illness. So you have religious and magical explanations for all of those things, which, in the course of time, eventually evolved into science — but not for a few hundred years. These women are associated through their family history with magic and goddesses, and then you have Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford — Elizabeth Woodville's mother — who was actually accused of being a practicing witch, and stands trial. Witnesses are produced who produce evidence: Little figures bound together with gold wire, which they say are the king and the queen being charmed to fall in love with each other. And she was found guilty in a court of law. Probably unfairly, probably wrongly, but there's enough belief there for someone to see that as a good way to attack her. Warwick attacks her that way. We may not believe in witchcraft, but if you're working as a serious historian in the period, you have to accept that they believe there's witchcraft. And if you're writing a novel set in the period, I think you would be insane not to acknowledge that powerful belief.

The White Queen has already premiered in the U.K., but it might be a trickier sell to American viewers who might not have the context for these historical figures. What advice would you have for getting into it?

Don't worry! [laughs] Everybody thinks the English know their history. They absolutely don't. This is unusual territory for any sort of entertainment because we've done a lot on the Tudors. Most people have got the Tudors straight after film after film and series after series. This is the family before them, and I think they're just as interesting. It's not a history documentary. It's entertainment. If you don't sit back and become immediately absorbed — if you don't fall in love with the characters and want to know what will happen to them — then it's failed as a piece of television. There's not going to be a test. It's not supposed to be hard work, it's supposed to be absolutely absorbing. If you want to go from The White Queen and study, if your interest is piqued, there's a lot of good material to go on and study. If, on the other hand, you want to watch it for pleasure, then watch it for your pleasure.

You're writing historical fiction about people who lived more than 500 years ago. What kind of historical fiction do you think someone living 500 years from now might write about us?

When I came to start writing history, I was taught in what some people called "The New History." From the 1950s, people started talking about the history of working people, and the history of unions, and the history of women, black history, the history of other nations. What you see is that, in a sense, all of these historians… say, if you're looking at the history of the [people featured in The White Queen]. People have been writing histories of these people for 500 years, and nobody until me thought that Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford was worth a book. There isn't a book published on her. There is only one published essay — and I wrote it. Nobody thought she was interesting, and I think she's the most extraordinary woman. So what you then have to do is project yourself. 500 years from now, people looking back will be saying, "How could a historian not see that the most interesting person in society is this?" I can't tell what it will be. I have a fantasy that someone 500 years in the future is going to say, "They did all this work. They did all this research. And they never checked out what the cats were thinking?" [laughs] Really, I do. I think it is going to be so outside what we can imagine.

The White Queen premieres on Starz at 8 p.m. EST on Saturday, August 10.

Scott Meslow is the entertainment editor for TheWeek.com. He has written about film and television at publications including The Atlantic, POLITICO Magazine, and Vulture.