Why Twitter doesn't punish people who make rape threats

And why that needs to change

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

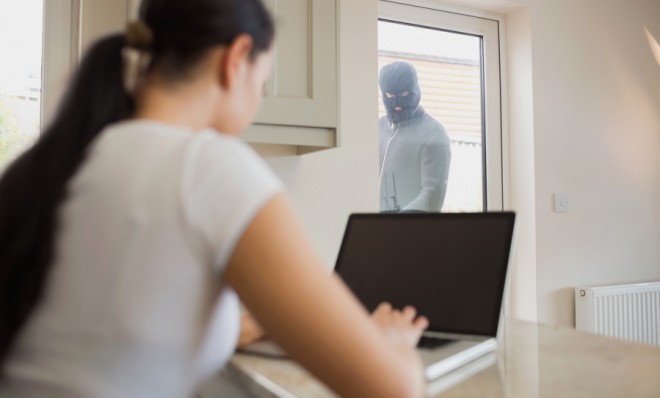

The internet can be a nasty place. Thanks to the masking power of anonymity-aiding pixels, it's easy for trolls to proceed relatively unchecked.

As a result, we've become gradually desensitized to the uglier side of human behavior, and have paid the price for it. Recent studies suggest the internet is making us meaner. And lonelier. And angrier. It's also raising our collective tolerance for what's acceptable to say in a public forum (at least when we're hidden behind a keyboard) in horrifying new ways.

Let's consider Twitter, which is often hailed as a free and fair global townhall for the digital age. Over the weekend, Caroline Criado-Perez, a feminist who campaigned to have Jane Austen's face stamped on British currency, became just the latest woman to receive a nonstop flood of death and rape threats from an unflinching army of online aggressors. According to BBC News, Criado-Perez suffered some 50 abusive tweets an hour for 12 hours straight, before Scotland Yard — not Twitter — traced the online lashing to a 21-year-old man who had coordinated the rhetorical attacks. (Twitter says it is looking into the abuse reports, but that it does not comment on individual accounts specifically.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Sadly, Criado-Perez is hardly the first woman to have to deal with the violent imaginations of young males who disagree with them. Blogger Lindy West has written extensively about the experience of being a woman navigating a deluge of Twitter rape threats. West had appeared on an FX TV show to debate the role of rape jokes in comedy. Then, in a Jezebel article called "If comedy has no lady problems, why am I getting so many rape threats?," West argued that "comedy's current permissiveness around cavalier, cruel, victim-targeting rape jokes contributes to (that's contributes — not causes) a culture of young men who don't understand what it means to take this stuff seriously."

Anita Sarkeesian, who writes about women's issues in pop culture (especially video games) under the handle Feminist Frequency, tweeted on Sunday that despite notifying Twitter multiple times, the rape threats she regularly receives are still deemed fit for publication by the service's moderators:

Hmmm. That's strange, considering the fact that Twitter's official policy notes:

"You may not publish or post direct, specific threats of violence against others." [Twitter]

Now, there are things you can say get yourself censored on Twitter. You can irk powerful suits by openly criticizing NBC's coverage of the Summer Olympics, for example. Or you can be a group of neo-Nazi skinheads trolling users in Germany. But Twitter's policing thus far has been sporadic and hard to predict.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To be clear: Twitter is a private company that can do what it pleases. But Facebook, the service's chief rival, tackled a similarly dicey issue in May, when graphic images and depictions glorifying "rape culture" began sprouting up on the social network. Initially, Facebook refused to pull the images — even though its community standards at the time explicitly barred "graphic content for sadistic pleasure," mind you — and only did so when companies were pressured into removing their advertising. Facebook later issued a half-hearted mea culpa promising to do "better."

As Twitter matures, it will need self-policing mechanisms in place to enforce a civil discourse without having to call the police when the threats become dire. Twitter, too, will need to do "better."

In the wake of the Criado-Perez controversy, an online petition is being circulated that calls for a "report abuse button" on tweets. "It is time Twitter took a zero tolerance policy on abuse, and learns to tell the difference between abuse and defense," write the petition's organizers. "The report abuse button needs to be accompanied by Twitter reviewing the T&C on abusive behavior to reflect an awareness of the complexity of violence against women, and the multiple oppressions women face." So far, the petition has garnered 50,000 signatures.

In response, Twitter says, "The ability to report individual tweets for abuse is currently available on Twitter for iPhone, and we plan to bring this functionality to other platforms, including Android and the web," and that users are encouraged to use its existing report form. But when asked by Wired on when that functionality would be available, the service declined to give a specific timeframe.

And yet, the antiquated idea that the internet should be kept separate from real life is increasingly a false dichotomy, as larger swaths of our lives are digitized into photos, tweets, Vines, bank accounts, and check-ins. In a real-life setting — say, a bar, where you're quasi-anonymous, anyway — shouting nasty threats at someone you disagree with is likely to earn you a mouth full of broken teeth. Real life has consequences, which is why in cyberspace, it isn't unreasonable to expect our most public forums, especially Twitter and Facebook, to facilitate contentious discourse while actively policing the kind of ugly hostility that the internet's veil encourages. And, at least so far, both services have failed to keep pace. Hannah Betts at the Telegraph says it best here:

Online society remains a society, with analogous rights and responsibilities, and needs to engage actively with such issues. If we want to be part of the not-so-new media, then we must take responsibility for confronting its more aberrant members. One thinks of Prospero's closing words about Caliban: "This thing of darkness / I acknowledge mine." [The Telegraph]