A brief history of our obsession with human-powered flight

Leonardo da Vinci would be proud!

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Flying through the air like a bird with little more than our muscles and our wits is a dream so etched into our being that the ancient Greeks immortalized it in myth. And while Icarus and his waxed wings may have hewed too close to the sun, human beings have tried — and failed — throughout history to defy the gravity that ceaselessly pulls us to Earth.

Some attempts at human-powered flight were more successful than others. In 9th century Spain, a Muslim inventor named Abbas Ibn Firnas was said to have successfully floated through the air using a winged apparatus that would later inspire a Renaissance polymath named Leonardo da Vinci. A little later on, an English monk in the 11th century named Eilmer of Malmesbury similarly strapped feathers to his arms and leaped from the top tower of Malmesbury Abbey.

He was airborne for a whole 15 seconds…and shattered both legs when he landed.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

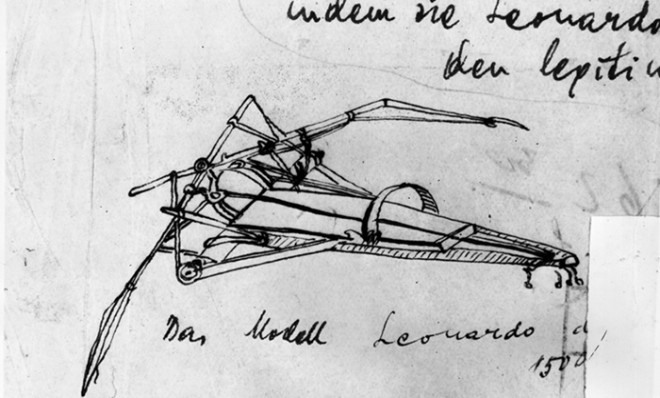

Da Vinci's designs may be history's most famous. Around 1485, the Renaissance inventor sketched out plans for the ornithopter — a bird-inspired, mechanical device equipped with beating wings. Later, there was an early prototype for what would eventually become the helicopter, which used a central, spiral-shaped rotor to literally screw its way into the air.

Over the next few centuries, human-powered flight continued to tease and elude adventurous inventors. Although a few managed to glide (however briefly), many with stars in their eyes lost their lives in crashes.

It wasn't until the advent of fossil fuels and combustion engines that the human component (at least as a source of power generation) was effectively rendered moot. More recently, however, the idea that man could fly under his own volition (and leg power) became a legitimate undertaking, if only to appease history.

There was 1988's Daedalus project, in which a team of MIT students built a bicycle-powered aircraft that set world records for both distance and time spent in the air.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And in 1980, the American Helicopter Society (AHS) issued the Sikorsky Prize — named after Russian aircraft designer Igor Sikorsky — which called on aeronautics engineers from across the country to design the most daunting contraption of all: A true, human-powered helicopter.

According to the rules, a winner had to fulfill three primary requirements:

1. It had to fly three meters into the air.

2. It had to be airborne for 60 seconds.

3. It had to keep the cockpit confined to a 10-square-meter area.

This, of course, was easier said than done. It wasn't until 1989 that a team of engineering students from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo managed to geta helicopter aloft — and even then, it only managed to hover just 20 centimeters off the ground. In 1994, a team of Japanese students pulled the curtains off the Yuri-I, a gigantic contraption that used four different rotors to generate lift. According to National Geographic, the quadcopter has been the standard ever since.

The advent of cheaper, more lightweight materials enabled a team of students from the University of Toronto to build the world's first human-powered ornithopter in in 2009, which, like da Vinci's original design, took to the air by flapping its wings.

Which brings us to the present: Earlier this summer, a Canadian team called AeroVelo (which is sprinkled with a few members from the University of Toronto's ornithopter team) have finally been awarded the elusive $250,000 Sikorsky Prize by building and piloting an enormous, four-rotor copter that managed to fulfill all three requirements. (For context, only five machines in the prize's history have ever even gotten off the ground.)

Behold: The "Atlas."

The apparatus' secret to success? According to AeroVelo's chief structural engineer Cameron Robinson, it came down to figuring out how to get the Atlas to stay within the Sikorsky challenge's parameters. "We realized it was not simply getting to three meters or flying for 60 seconds, but staying inside the box," Robinson tells National Geographic. The team realized that by using the lightweight craft's flexibility as an asset, they could use the pilot's lean to dictate where the rotors tilted. "It was very intuitive, a very fast response," says Robertson. By foregoing a traditional piloting system, "it also allowed us to save 8 percent of the helicopter weight."

Indeed, watching the Atlas hover in the air is quite a spectacle. But it does raise the question: Is the human-powered helicopter too impractical, too cumbersome to have much real-world application? Yeah. Sure.

On the other hand, it's worth remembering that reaching toward the sun wasn't very practical to begin with.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict