The great Beanie Baby bubble

Shockingly, stuffed animals are not a fantastic investment after all

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Price bubbles appear to be closely tied to human psychology.

A price bubble happens when investors pile into an asset or class of assets, usually believing that the price will continue to rise. This can be due to a theory — like the one that "housing prices will never fall" — or simply come from investors and speculators seeing the rising price, and jumping on an opportunity to ride the tide.

Bubbles often accompany times of great technological change and innovation — like the advent of radio, automobiles, and interstate highways in the 1920s, or the advent of the internet in the 1990s. This may be because technological change twists and confuses people's expectations and beliefs about the future. An economic boom based on a new technological paradigm can in the minds of the masses create the impression that the boom will last forever, and prices will either continue to rise indefinitely or reach a "permanently high new plateau."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The 1990s was not only a period of great technological change — the birth of internet, the growth of the computing industry, a flood of Asian-made consumer electronics, the human genome project — it was also a time of relatively great geopolitical calm. Oil was cheap, and therefore plastics, energy, and transport were cheap. The Soviet Union had collapsed, and the threat of world war seemed to have receded entirely. Francis Fukuyama mistakenly called it The End of History. It was a decade of unparalleled optimism.

The most famous price bubble of that optimistic era was the NASDAQ, where technology and internet stocks like Amazon, Webvan and Pets.com attracted huge investment. Many of these businesses went bust when the NASDAQ bubble burst in 2000.

But there was another smaller and less famous bubble that occurred at almost precisely the same time. This was the bubble in Beanie Babies, a series of stuffed toys produced by Ty Toys.

A number of factors led to Beanie Babies' initial popularity and meteoric rise as collectibles. They were originally envisioned as a set of inexpensive, high-quality stuffed animals, with prices set around $5, low enough to seem affordable to children. Ty avoided large retailers, and marketed Beanie Babies through smaller gift shops and collectible outlets, giving their products a certain luster in the eyes of collectors.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Accounts and news stories of rare beanies selling for thousands of dollars created a wider awareness of Beanie Babies, and magazines such as Mary Beth's Bean Bag World — which at its peak sold over 650,000 copies a month on newsstands — helped keep the market orderly by giving buyers and sellers a reference point for negotiations.

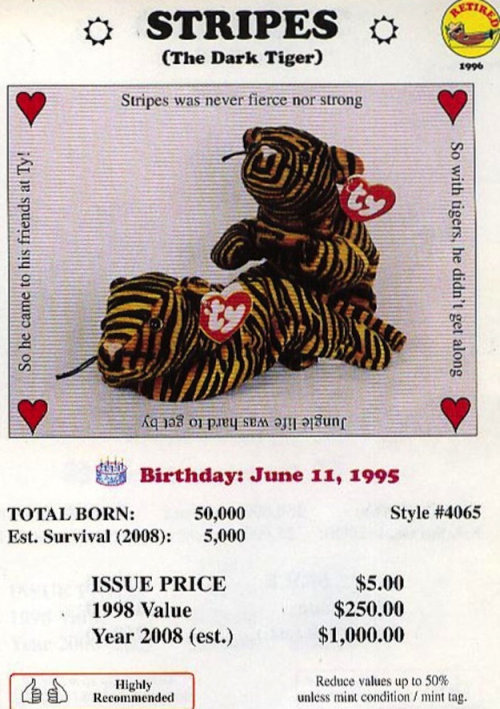

In 1998, so-called "investment-grade" rare Beanie Babies were projected to be worth vastly, vastly more than their $5 purchase price.

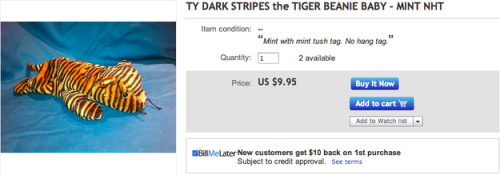

Today, Stripes is selling for less than 1 percent of its 2008 estimate:

People who paid the 1998 list price of $250 hoping to cash out for $1,000 in 2008 got seriously burned. In August 1999, Ty shocked collectors by announcing that it would stop making Beanie Babies on Dec. 31, 1999. The company never publicly explained its reasons, but auction prices had begun to stagnate, so many saw the move as a desperate effort to limit supply and boost prices among collectors, thus continuing the mania. It did not work.

With today's value at $10, buyers of so-called "investment-grade" beanies like Stripes at $250 have lost 96 percent of their initial capital. And similar falls occurred across the range of Beanie Babies — the 1998 and 1999 prices have dramatically fallen and remained low ever since.

The Beanie Baby phenomenon taught some tough lessons about speculative bubbles and value in economics to a young audience. Beanie Babies demonstrate that scarcity or a fixed supply is no guarantee of future price gains.

To make a profit on an investment or commodity, someone in the future must be willing to pay more than you paid. If the largest reason bringing people into the market and driving a price upward is price speculation and the hope of future profits, then it is very likely an asset bubble. In the case of Beanie Babies, the asset bubble ran out of steam and deflated. Once prices started to decline, all of the demand dried up. With weak demand, prices have remained depressed.

That said, value is subjective; people who purchased Beanie Babies for some reason other than price speculation may be perfectly happy because they like to actually play with them as toys.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy