What is activist investing, and why is it so popular?

Recently acquired meat company Smithfield Foods could be split into three pieces because of a vocal, highly invested hedge fund

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Just two weeks after Chinese meat giant Shuanghui International agreed to buy American pork king Smithfield Foods for $4.7 billion ($34 a share), activist hedge fund Starboard Value has posed a different idea: Break the company into three pieces — U.S. pork production, hog farming, and international sales — and lift its value to a whopping $7.1 billion ($44 to $55 a share).

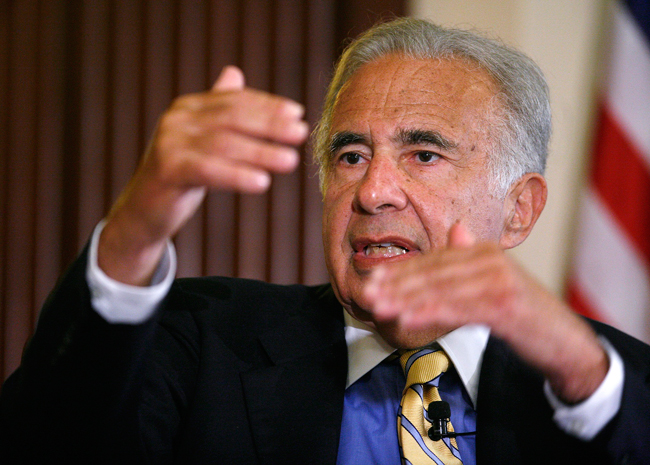

Starboard's suggestion (a pretty strong suggestion, since it owns 5.7 percent of Smithfield's shares) follows a growing trend in activist investing, where activists are targeting larger and larger companies. In March, David Einhorn pushed Apple to cough up billions in dividends; in May, Daniel Loeb suggested Sony break off Sony Entertainment; Carl Icahn continues to needle Dell — the list goes on.

What is activist investing?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Similar to the corporate raiders of the 1980s, activist investors, either by themselves or in groups, vacuum up a large number of shares of a mismanaged company, often securing themselves a chair at the board table. The point is to gain enough control to radically change how the company is run, which could mean replacing management, reorganizing spending, splitting the company in pieces like with Smithfield — anything to increase the company's value and kick up the stock price.

Why is this type of investing gaining popularity?

"Low interest rates and perky stock markets mean that assets being divested can fetch top dollar," says The Economist. And hedge funds have more money than ever — $73 billion — to throw around.

At the same time, the stigma once associated with activist investing has started to melt away. "They are more accepted by large institutional investors and corporate managers," Kenneth Squire, a former mergers lawyer tells Business Insider. The positive vibes make it easier for activists to drum up additional support — and harder for companies to resist change. The Economist:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Some American pension funds have even placed money with activists to keep companies on their toes. A side-effect of bringing big investors on board is that arguments are often less noisy. Institutions are still loathe to be dragged into messy fights played out in the pages of the Wall Street Journal. Most activism now takes place privately, says Barry Rosenstein of Jana Partners, a hedge fund. [The Economist]

The result of more money, a friendly stock market, and outside support is that that activist investing — for at least a few top dogs — has proved wildly successful. Between January 2000 through May 28, Carl Icahn's Icahn Enterprises earned a 1,122 percent return (with reinvested dividends), compared to the Dow which earned 185 percent. And the activists themselves aren't the only ones benefiting. Icahn, "Wall Street's richest man," says in Forbes:

Critics of activism state that activism may be good for the activist but not for other stockholders. Yet shareholder value has risen by many billions of dollars in the companies we have targeted over the years. I believe this proves conclusively that all shareholders, not just us, benefit from our involvement, and, perhaps even more important, the changes we institute at these companies cause them to become more productive, and therefore enable them to compete with foreign companies more efficiently, which in turn creates more jobs–something this country needs. [Forbes]

What are the risks?

Sometimes activists make decisions for a company that don't pan out. (See: Bill Ackman personally recruiting Ron Johnson to run JC Penney.) Failed strategies equal losses, not just for the activist, but also the other shareholders and the company — and the smaller investors who followed the activist with high hopes for the company's future, says Richard Satran at Business Insider:

Smaller investors or hedge-fund copycats play follow the leader whenever Icahn and Ackman file 13D statements, disclosures required whenever an investor takes a 5 percent position in a company's voting shares that may hint at plans to push for measures to influence company performance, which can range from a change of strategy to tossing out management.

Individual investors who mimic the big investors are taking a risk of a big loss because the targets are often companies with problems, and the activist's strategy could backfire and the company's situation could worsen. Moreover, the activist can dump the position at any time without notifying the public, since the position reports come out after the fact. It's like trying to follow a UFC fight from outside the auditorium and deciding what is happening based on the roar of the crowd. [Business Insider]

Carmel Lobello is the business editor at TheWeek.com. Previously, she was an editor at DeathandTaxesMag.com.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy