What we know about PRISM, the NSA's data goldmine

The agency's powerful data-scooping tool exists, and it isn't supposed to read your emails

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

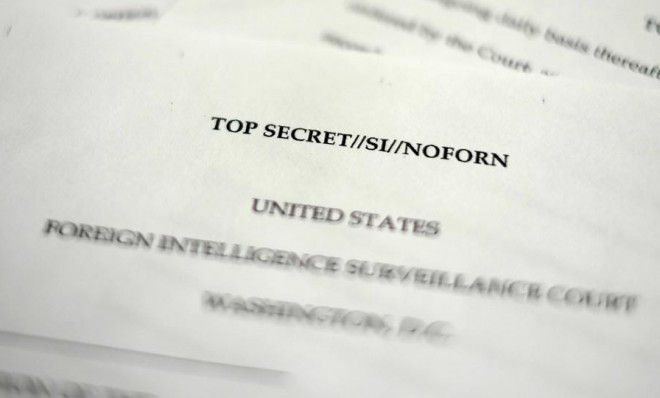

We now know a lot more about PRISM, the top secret National Security Agency program that apparently allows the U.S. government to mine all sorts of electronic communications, than we did Thursday morning. For one (big) thing, we know it exists, thanks to simultaneous reports in The Washington Post and Britain's The Guardian.

But there's plenty we don't know, because the program, after all, is a classified secret. The disclosure of the PRISM program, launched in 2007, was accompanied by the leak of a training PowerPoint presentation, The Washington Post says, by a "career intelligence officer" who has had first-hand experience with PRISM. The officer wanted "to expose what he believes to be a gross intrusion on privacy." You can read some of the PowerPoint slides, and Director of National Intelligence James Clapper's response to the leak.

Based on the primary documents and subsequent reporting, here's what we know (or probably know) about the NSA's electronic snooping treasure trove:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What does PRISM do?

The Washington Post says PRISM allows the NSA and FBI to tap "directly into the central servers of nine leading U.S. internet companies, extracting audio and video chats, photographs, emails, documents, and connection logs that enable analysts to track foreign targets."

The nine companies (in the order they allegedly joined the program) are Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, PalTalk, YouTube, Skype, AOL, and Apple. In other words, says the Post, "most of the dominant global players of Silicon Valley." The type of data the NSA can access "varies by provider," one PowerPoint slide notes.

But "many of the companies quickly denied they were involved, adding a note of confusion as to how the program might operate," says The Wall Street Journal. The Washington Post and Guardian say it appears that, based on the leaked documents, PRISM allows NSA "collection managers" to dip into the massive data collections from these nine internet giants and fish out information, stored or in real time, based on various search criteria.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"The PRISM program is not a dragnet, exactly," says The Washington Post. "From inside a company's data stream the NSA is capable of pulling out anything it likes, but under current rules the agency does not try to collect it all." And the Post's leaker says the program is so powerful, "they quite literally can watch your ideas form as you type."

Marc Ambinder at The Week says his sources describe PRISM as "a 'front end' system, or software, that allows an NSA analyst to search through the data and pull out items of significance, which are then stored in any number of databases." The NSA wants this, he says, because given the different ways information travels across the internet, it needs a system that can "handle several different types of data streams using different basic encryption methods." PRISM can do that.

"The idea is to create a mosaic," one official tells Ambinder. "We get a tip. We vet it. Then we mine the data for intelligence." In all, as many as 50 companies including credit card companies and major phone providers participate in providing real-time user data to the NSA, Ambinder says.

So, does the NSA have unfettered access to Google, Apple, and Microsoft's servers?

Most of the companies specifically say no, the NSA doesn't have access to its severs. And "it is possible that the conflict between the PRISM slides and the company spokesmen is the result of imprecision on the part of the NSA author," concedes The Washington Post.

Given the secrecy of the program, Ambinder says, "it is not clear how the NSA interfaces with the companies."

Several of the companies mentioned in the Post report deny granting access to the NSA, although it is possible that they are lying, or that the NSA's arrangements with the company are kept so tightly compartmentalized that very few people know about it. Those who do probably have security clearances and are bound by law not to reveal the arrangement.... It is possible, but not likely, that the NSA clandestinely burrows into servers on American soil, without the knowledge of the company in question, although that would be illegal. [The Week]

According to "people briefed on the arrangement," says The New York Times, "the companies have negotiated with the government technical means to provide specific data in response to court orders." Those orders, as with the recently revealed Verizon phone-records culling, would come from the secretive Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC).

Can the NSA read my emails and watch my video chats?

Assuming you're an American, the answer is supposed to be no. PRISM scoops up data from U.S. servers, because much of the world's data flows through U.S. servers, but the information is supposed be from or to suspected foreign terrorists. Without naming the program, DNI Clapper says that PRISM "cannot be used to intentionally target any U.S. citizen, any other U.S. person, or anyone located within the United States."

All such surveillance activities, Clapper adds, "involve extensive procedures, specifically approved by the court, to ensure that only non-U.S. persons outside the U.S. are targeted, and that minimize the acquisition, retention, and dissemination of incidentally acquired information about U.S. persons."

What that means in practice, says The Week's Ambinder, is that "PRISM works with another NSA program to encrypt and remove from the analysts' screen data that a computer or the analyst deems to be from a U.S. person who is not the subject of the investigation." If an analyst wants to keep on monitoring or analyzing the flagged data stream, a FISC court has to sign off.

Armed with what amounts to a rubber stamp court order, however, the NSA can collect and store trillions of bytes of electromagnetic detritus shaken off by American citizens. In the government's eyes, the data is simply moving from one place to another. It does not become, in the government's eyes, relevant or protected in any way unless and until it is subject to analysis. Analysis requires that second order....

One official likened the NSA's collection authority to a van full of sealed boxes that are delivered to the agency. A court order, similar to the one revealed by The Guardian, permits the transfer of custody of the "boxes." But the NSA needs something else, a specific purpose or investigation, in order to open a particular box. The chairman of the Senate intelligence committee, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, said the standard was "a reasonable, articulatable" suspicion, but did not go into details. [The Week]

The problem is that the criteria used to determine who's American are not "very stringent," says The Washington Post. "Analysts who use the system from a web portal at Fort Meade, Md., key in "selectors," or search terms, that are designed to produce at least 51 percent confidence in a target's 'foreignness.'" What's more, "training materials obtained by the Post instruct new analysts to make quarterly reports of any accidental collection of U.S. content, but add that 'it's nothing to worry about.'"

A couple of Senate Democrats have been warning about NSA overreach, but were unable to be specific because of the programs' security classification. In December 2012, before Congress re-authorized the 2008 FISA Amendments Act, Sen. Mark Udall (D-Colo.) cautioned: "As it is written, there is nothing to prohibit the intelligence community from searching through a pile of communications, which may have been incidentally or accidentally collected without a warrant, to deliberately search for the phone calls or e-mails of specific Americans."

Given the almost unimaginable amount of data that emanates from American web users every day, there's almost no chance anything you write or say would be read or seen by an actual person, even if the NSA protocols fail (or are ignored). But even that very slim possibility is kind of creepy, and it seems dangerous to ignore the potential for abuse.

Is the program legal?

Yes. It was authorized in the FISA Amendments Act. Unlike the warrantless surveillance programs under George W. Bush, which preceded PRISM, this program is also under the purview of the FISA court.

Clapper says the program is covered, specifically, by Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, then notes, pointedly that "activities authorized by Section 702 are subject to oversight by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, the executive branch, and Congress." What's more, he says, that statute was "recently reauthorized by Congress after extensive hearings and debate."

Anthony Romero of the American Civil Liberties Union isn't impressed. "A pox on all the three houses of government," he tells The New York Times. "On Congress, for legislating such powers, on the FISA court for being such a paper tiger and rubber stamp, and on the Obama administration for not being true to its values."

Have there been any tangible benefits from PRISM?

That's hard to say. Clapper insists that the "information collected under this program is among the most important and valuable foreign intelligence information we collect, and is used to protect our nation from a wide variety of threats." But he doesn't provide any examples, and probably can't, given the secrecy surrounding the program.

Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Mich.), the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, said Thursday that the NSA's phone-metadata collection program — part of which Clapper just declassified — helped prevent a "significant domestic terrorist attack" within "the last few years," for example, but said the specifics are classified so he can't elaborate.

What's clear is that PRISM is highly valued by the intelligence community. The Washington Post:

An internal presentation of 41 briefing slides on PRISM, dated April 2013 and intended for senior analysts in the NSA's Signals Intelligence Directorate, described the new tool as the most prolific contributor to the President's Daily Brief, which cited PRISM data in 1,477 items last year. According to the slides and other supporting materials obtained by the Post, "NSA reporting increasingly relies on PRISM" as its leading source of raw material, accounting for nearly 1 in 7 intelligence reports. That is a remarkable figure in an agency that measures annual intake in the trillions of communications. [Washington Post]

The Guardian adds that the NSA has issued more than 77,000 PRISM-based "reports" — or requests for further investigation of a certain communication — and now logs more than 2,000 PRISM reports a month.

The big question, then, is this: Is this massive, powerful surveillance apparatus worth it?

The revelation about PRISM "trains the spotlight on a sticky dilemma," says Byron Acohido at USA Today.

It's hard to argue against leaving no stone unturned in preventing another 9-11 terrorist attack. On other hand, history is replete with examples of autocrats using intelligence-gathering to oppress. [USA Today]

Civil libertarians believe the program is an unconscionable — perhaps even unconstitutional — intrusion on privacy, and that the government can't be trusted to monitor itself. Most members of Congress so far have said PRISM and the NSA's other tools are worth it to protect American from terrorism. Many Americans are ambivalent, or fall somewhere in between.

Benjamin Franklin famously said: "They who can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety." But Franklin would never have been blamed if Americans died in an act of terrorism.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy