How a Ghost Army of American artists helped defeat Hitler

A new documentary shines a light on an audacious WWII regiment of actors, painters, and other illusion-spinners

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The CIA Iran rescue operation featured in Argo isn't the first time the U.S. has used the arts to foil a bitter enemy. This week, PBS premiered a documentary on the U.S. Army's 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, nicknamed the Ghost Army, a group of 1,100 handpicked soldiers in World War II who played an unlikely, but pivotal, role in the Allied victory over Nazi Germany.

If you've never heard of the Ghost Army, you're in good company. The unit was a classified secret until 1996 — it's still partially classified — and Rick Beyer, the director of The Ghost Army, only found out about the covert troop of artist-warriors by chance, in a Boston-area café, from the niece of one of the unit's veterans.

Armies have been using subterfuge to fool enemy forces for eons, but the Ghost Army was unusually audacious, and especially good at its job: Designing and deploying inflatable tanks, airplanes, and artillery, plus sound effects and other illusion-spinning tactics, to convince the German army that the Allied forces were stronger and more omnipresent than they were.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That success was not an accident, says Megan Garber at The Atlantic. Veterans from the 23rd include fashion designer Bill Blass, minimalist painter Ellsworth Kelly, and photographer Art Kane, who went on to capture Harlem's jazz greats in an iconic 1958 photograph as well as portraits of folk and rock legends from Bob Dylan to the Rolling Stones.

Blass and his brothers in arms were recruited from art schools and ad agencies. They were sought for their acting skills. They were selected for their creativity. They were soldiers whose most effective weapon was artistry. [Atlantic]

According to one account, the idea for the Ghost Army came from the actor Douglas Fairbanks Jr. In short, says Garber, the illusion-spinners of the 23rd saved tens of thousands of Allied lives by "taking 'the art of war' wonderfully literally."

You can get a good sense of how the Ghosters spun their magic in the trailer:

One of the big guns in the unit's arsenal of tricks was the 90-pound inflatable tank:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

(National Archives)

The inflatable tanks would be mixed in behind a few real tanks to make it seem like a large force was amassing, or poorly camouflaged so that enemy reconnaissance would pinpoint a coming attack in the wrong location. The 23rd was often deployed near enemy lines, and this tactic wasn't without serious risk: "Deflation was a constant concern — a limp gun barrel on an artillery piece was something of a giveaway," says Neil Genzlinger in The New York Times. "And sometimes, more dangerously, the hope was that the fake army would draw fire, sparing troops elsewhere."

Between D-Day in 1944 and Germany's surrender a year later, "the Ghost Army devised more than 20 deceptive operations, phony convoys, and phantom divisions" in France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Germany, says Susan Karlin at Fast Company. They used the specific Morse code patterns of particular Allied operators to fool German eavesdroppers about the location of U.S. units, broadcast fake radio transmissions, and used giant portable speakers to send convincing, mixed-on-the-fly soundscapes of pre-recorded audio of military convoys thundering through the countryside up to 15 miles away. (Below, watch a one-time secret War Department film on the type of sonic deception used by the Ghost Army.)

Soldiers even hung out at local cafés, spinning yarns for eavesdropping spies. The effort culminated along the Rhine in the final days of the war, in which thousands of lives depended on a convincing performance.

"When I began working on this, it was just an interesting story that I wanted to tell," says Beyer. "But somewhere along the way, it became a quest to make sure that this amazing group of guys and the astonishing, almost unbelievable, things they did are not forgotten. I knew that if I didn't do this documentary, they would be gone, and their stories with them." [Fast Company]

Here's what the powerful, portable Sonic Halftracks looked like:

(National Archives)

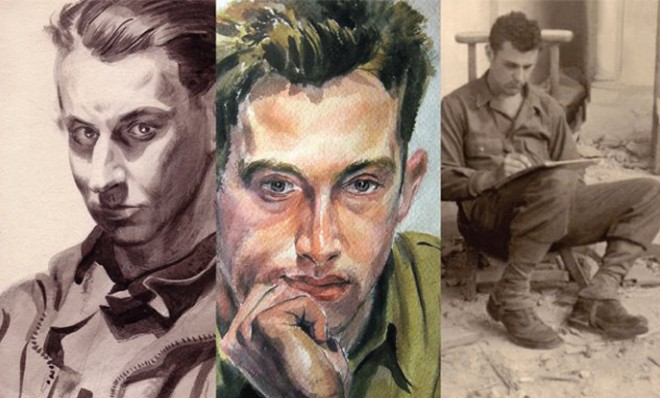

But because the unit was filled with artists, says Fast Company's Karlin, "during quiet moments, they would often sketch and paint their surroundings, offering a fine-art chronicling of the mission." Some of that artwork is on exhibit until June 9 at the Edward Hopper House Art Center in Nyack, N.Y. You can see some of it here. In this painting, by Arthur Shilstone, two Frenchmen stumbled upon four Ghosters lifting one of the inflatable tanks. Noting their shocked reaction, Shilstone told the men, "The Americans are very strong."

(Arthur Shilstone)

The 23rd staged its last big performance "at the final crossing of the Rhine in March 1945, near the war's end," says Genzlinger in The New York Times. But in that battle, as "throughout their mission, members of the unit knew they were having an effect only when they drew fire."

The more amorphous hoped-for result, sowing seeds of confusion, was harder to pin down. So veterans of this part of the war have had to content themselves with a less cut-and-dried memory of their contributions than many carried away from the conflict. "One mother or one new bride was spared the agony of putting a gold star in their front window," Stan Nance, a sergeant in the radio unit, says. "That's what the 23rd Headquarters was all about." [New York Times]

You can find which PBS stations are airing the documentary, and when, here. Here's an alternative trailer for The Ghost Army:

Here's a World War II film about the U.S. Army's sonic deception technologies:

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.