Scientists for the first time create human stem cells through cloning

A breakthrough in stem cell research could pave the way for new medical treatments

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

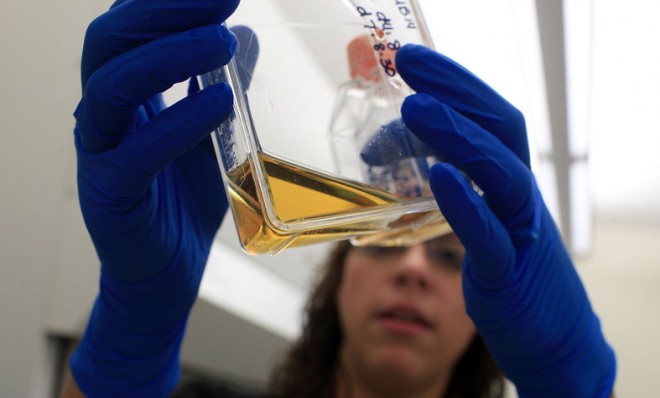

A team of scientists have successfully cloned human embryos that can produce stem cells, a major breakthrough that could lead to new medical treatments — and, potentially, human cloning.

Scientists from Oregon Health and Science University, reporting their finding Wednesday in the journal Cell, said they had taken a baby's skin cells and combined them with human eggs. The result? Human embryos genetically identical to the original baby that, crucially, were able to produce fresh stem cells.

The process, known as a somatic-cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), involves taking the nucleus of one cell and implanting it into an unfertilized egg that has had its nucleus removed.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"The egg 'reprograms' the DNA in the donor cell to an embryonic state and divides until it has reached the early, blastocyst stage," explains Nature's David Cyranoski. "The cells are then harvested and cultured to create a stable cell line that is genetically matched to the donor and that can become almost any cell type in the human body."

That technique is essentially what scientists used to create Dolly, the infamous cloned sheep, in the mid 1990s. Since then, however, researches had been unable to successfully recreate that process in human cells.

Stem cells are incredibly versatile, as they can be turned into any kind of cell in the human body. As such, scientists have long hoped they could one day use stem cells to grow new tissues or organs, and to treat a host of serious, degenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

"It's been a holy grail that we've been after for years," the University of Pennsylvania's Dr. John Gearhart told NPR.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A key to the latest breakthrough, it turns out, was caffeine. The researches found that adding a little of that stimulant helped protect the eggs and allowed them to develop to a point at which they produced stem cells that could then be harvested.

However, the process is not without its critics, who fret that the practice is immoral and could lead to human cloning. Boston Cardinal Sean O’Malley warned, "This means of making embryos for research will be taken up by those who want to produce cloned children as 'copies' of other people."

The researchers, however, insisted that their methods would not result in viable human clones. They claimed the same technique had been tried many times in monkeys, yet it never produced clones.

While the discovery is certainly a major breakthrough in itself, it may not have wide-ranging repercussions in the field. As The Boston Globe's Carolyn Y. Johnson points out, scientists had already discovered an easier way of producing stem cells that, while not without its limitations, had somewhat negated the need to produce stem cells via SCNT.

From the Globe:

The discovery would no doubt be a bigger deal if in 2007, scientists had not discovered that there was a different, simpler way to create stem cells that bear a patient’s own genome and are pluripotent, possessing the capacity to develop into any of the myriad cells and tissues in the body. Instead of replacing the genetic material in an egg with the genome of a patient — the procedure known as cloning — the researchers found they could flip genetic switches that turned back time, reprogramming normal skin cells and turning them into embyronic-like stem cells.

This method negated the difficult need for egg donors, and avoided many of the ethical quandaries that had bogged down the field. [Boston Globe]

Jon Terbush is an associate editor at TheWeek.com covering politics, sports, and other things he finds interesting. He has previously written for Talking Points Memo, Raw Story, and Business Insider.