Trap streets: The crafty trick mapmakers use to fight plagiarism

These make-believe places aren't nearly as prevalent as they used to be. And yet...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As recently as 2009, in the rural English county of Lancashire, a small town called Argleton could easily be found on Google Maps, just east of the A59 motorway. A cursory online search for the town was replete with websites for businesses, real estate listings, local weather, and even ways to find yourself a hot Friday-night date.

There was one problem, though. If you drove through the English countryside trying to find Argleton, you'd quickly find yourself confused and lost. There were no buildings, street signs, or townspeople — just open fields of untouched grass.

The town never existed anywhere other than cyberspace, where it was represented visually by one of Google's teardrop-shaped pins.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Argleton was a phantom town.

***

At the time, Google said Argleton's inclusion in its mapping software was the result of human error, and the "mistake" was soon deleted. The more likely story, though, is that Argleton was an example of a copyright trap, which cartographers have long used to catch would-be thieves from stealing their hard work. In this case, either Google was laying the bait for a competitor (hey, Bing?) or the mystery town was inserted in analog form long ago by Tele Atlas, the Netherlands-based company that supplied Google Maps with its initial framework.

The term "trap street" refers to fake roads and other fictional destinations like Argleton that are intentionally sprinkled on a map to discourage competitors from plagiarism. The idea's existence isn't so dissimilar from the fake entries long employed by the creators of other reference materials. The 1975 edition of the New Oxford American Dictionary, for example, contained an entry for the word "esquivalience," which was listed as a late 19th century English term for "the willful avoidance of one's official responsibilities." It was eventually revealed that the word was one of six fake terms inserted by the edition's lexicographers, a term anti-plagiarists call Mountweazels. (The word is derived from a ghost entry for Lillian Virginia Mountweazel in the 1975 New Columbia Encyclopedia.) "It was an old tradition in encyclopedias to put in a fake entry to protect your copyright," Richard Steins, one of the volume's editors, told the New Yorker. "If someone copied Lillian, then we'd know they'd stolen from us."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

While the internet puts plagiarists at the mercy of the crowd, traditional copyright traps served a much smaller audience, and back in the day, could be found in just about any reference volume. For example, in Robert Hughes' The Music Lovers' Encyclopedia, first published in 1903, there existed a mouthful of an entry for a Maori drum called a "zzxjoanw." The entry was only exposed as a sham decades later, in 1976.

Trap streets serve the same purpose. Mapmaking, after all, is extremely difficult. Long before Google sent out its fleet of Street View cars, converting the real world into a two-dimensional piece of paper required valuable time and labor. It's easy to see why you'd want to protect the result of your hard work.

Although they'd probably never admit it publicly, prominent mapmakers like Rand McNally used trap streets until at least the 1980s, when the practice was whispered to be discontinued. And yet, fictitious roads, like La Taza Drive in Upland, Calif., still somehow managed to get inked into the 1997 Thomas Guide.

To their credit, mapmakers tried to make trap streets as unobtrusive to a user's route as possible. "The make-believe streets are little ones," Thomas Brothers vice president Barry Elias said in a 1981 Los Angeles Times article (via Straight Dope). "The mythical avenues normally run no longer than a block, dead end, and are shown with broken lines (as though they are under construction)."

Things changed for mapmakers in the mid-1990s, after the Supreme Court ruled in Feist v. Rural Telephone Company that facts weren't eligible for copyright protections, and didn't count as intellectual property. Around the same time, in Alexandria Drafting Co. v. Amsterdam, a federal district court dealt a devastating blow to mapmakers, ruling that "the existence, or non-existence, of a road is a non-copyrightable fact." [PDF] American mapmakers suddenly lost their preferred strategy of sussing out and punishing copycats.

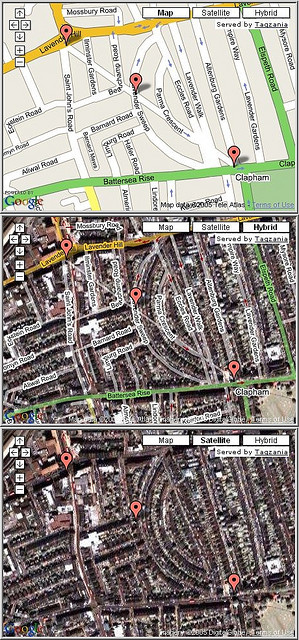

Not so in the U.K. In 2001, the Automobile Association was famously ordered to pay £20 million for infringing on another outfit's mapping copyrights. The giveaway? Little style markers — or "fingerprints," like specific road widths — which were purposefully used to nab crooks. In fact, some who've poured through Tele Atlas guides, like contributors to this Wiki, claim that London maps still contain a few dozen trap streets that don't actually exist.

Nowadays, though, trap streets are a relic — a secret symbol of an analog past. (Although, as Argleton suggests, they still may pop up from time to time.) Other than Google's ongoing efforts to layer information atop geographical data, the future of mapmaking lies in collaborative, Wikipedia-style efforts like Open Street Map, which draws on users to contribute and self-police the project for accuracy.

Open Street Map's data is apparently reliable enough; MapQuest, the once-preeminent software supplanted by Google Maps, even uses Open Street Map's crowdsourced data to build its own. "The importance of big data providers has waned so much as Open Street Map has increased in popularity," cartographer Tim Lohnes of Lohnes+Wright GIS and Mapping tells me in an email. "Trap streets just seem like a distant memory."

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention