Will Aaron Swartz's suicide spark copyright reform?

The 26-year-old wunderkind's death is bringing laws written a half-century ago back into the spotlight

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

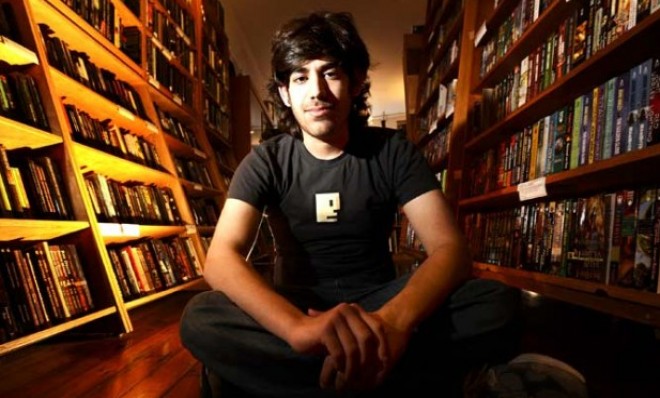

Aaron Swartz, the young architect of RSS and Reddit, was found dead in his Brooklyn apartment last Friday, an apparent suicide. He was 26. The emotionally fragile co-founder of progressive organization Demand Progress had been locked for nearly two years in a draining legal battle with the U.S. government, accused of illegally downloading more than 4 million files from scholarly database JSTOR using a laptop hidden inside a Massachusetts Institute of Technology closet. Although JSTOR and MIT both decided not to pursue charges, Swartz faced as many as 35 years in prison and $1 million in fines from the feds' case. In the months leading up to his death, Swartz was reportedly in deep financial trouble thanks to his legal expenses.

Swartz was never quiet about his long battle with depression, and his death has hit a nerve. Indeed, many of his allies are rallying around this tragedy to demand reforms in the way copyright cases are handled. Some accuse the prosecution, led by U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz, of trying to make an example of Swartz, whose gifts for technology and foresight were only rivaled by his gift for making enemies in high places. "Aaron's death is not simply a personal tragedy," writes his family on a tribute site. "It is the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach."

On Sunday, hacktivist group Anonymous broke into MIT's website and called for an overhaul of intellectual property and computer crime laws. "We call for this tragedy to be a basis for a renewed and unwavering commitment to a free and unfettered internet, spared from censorship with equality and access and franchise for all." (The message has since been taken down, and Anonymous has apologized for using MIT's website to deliver its message.)

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Of course, not everyone agrees with the calls for reform. "Stealing is stealing," said U.S. Attorney Ortiz in a 2011 news release, "whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data, or dollars. It is equally harmful to the victim whether you sell what you have stolen or" — in Swartz's case — "give it away."

Many, however, argue that in Swartz's case, the proposed punishment didn't fit the alleged crime. And to Swartz, the downloading of academic files was an act of civil disobedience — one that illustrated that it remains quite difficult for the public to access academic studies funded by their tax dollars.

"It's one thing to stretch the law to stop a criminal syndicate or terrorist organization," says Tim Wu, a professor at Columbia Law School, at The New Yorker. "It's quite another when prosecuting a reckless young man."

The act was harmless — not in the sense of hypothetical damages or the circular logic of deterrence theory (that’s lawyerly logic), but in John Stuart Mill’s sense, meaning that there was no actual physical harm, nor actual economic harm. The leak was found and plugged; JSTOR suffered no actual economic loss. It did not press charges. Like a pie in the face, Swartz’s act was annoying to its victim, but of no lasting consequence. [The New Yorker]

Stealing in the analog world is easy to define, says lawyer Michael Phillips at BuzzFeed. If you take a book from a bookstore, you physically have it. The bookstore can't sell it. You can destroy it so it won't exist anymore. And you can even place it back on the shelf if you change your mind. But when it comes to digital files, our traditional definition for theft and property gets increasingly murky.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The current, widely held concept of digital stealing is that it's a form of copyright infringement. You might have heard of the Tenenbaum case, where a college kid who downloaded 30 songs from file-sharing sites was held liable for $675,000 in copyright damages instead of $30, the cost of those songs on iTunes. Steal 30 songs by taking a CD out of a Best Buy, you've done $30 of criminal damage. Download 30 songs, and you're a copyright infringer. At this rate, the iPhone in your pocket is carrying $100 million in stolen goods. This copyright model makes no sense. [BuzzFeed]

And in Swartz's case, many of the academic articles he downloaded from JSTOR are already in the public domain — "so many that the prosecution did not even charge [Swartz] with copyright infringement," says Phillips.

What was Swartz charged with then? Not theft. Instead, he was charged with a computer fraud statute based on obscure language from a wire fraud statute originally written in 1952. "These are laws written for the age of telegrams," argues Phillips.

Many of Swartz's supporters are now calling for a renewed focus on rewriting antiquated digital copyright laws for the modern age, particularly as our lives become increasingly measured in megabytes. Following Swartz's suicide, the U.S. District Court in Massachusetts has dismissed its case against Aaron Swartz, and a White House petition is being circulated to remove U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz for "overreach." The U.S. Attorney's office has declined to discuss the case, with a spokeswoman saying, "We want to respect the privacy of the family and do not feel it is appropriate to comment at this time."