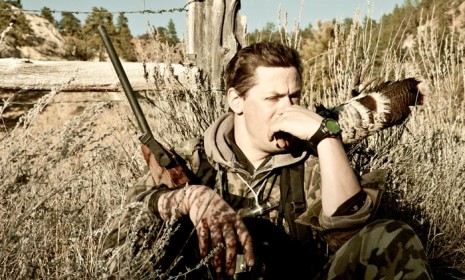

Inside the mind of a hunter

Alone in the wilderness, says Steven Rinella, I find joy and purity as a human predator in search of food

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

AT THIS MOMENT, there are fewer hunters on earth than at any other time in human history. Only about 5 percent of Americans hunt, down from about 7 percent a decade ago. For me hunting is a form of resistance, an act of guerrilla warfare against the inevitable advance of time, when hunting eventually disappears. When I'm asked why I hunt, I can answer best with hunting stories, and two come to mind.

The first took place on a recent spring day when I was hunting turkeys in the Powder River Badlands of southeastern Montana with my brother Matt. Early that morning we left Matt's pack llamas, Timmy and Haggy, tethered near our camp. Matt headed south, and I went into the next valley to the west. In the late morning I started after a tom, or male turkey, that I'd heard gobbling several hundred yards away. I followed the bird for close to an hour, only once catching a glimpse of it. He was walking fast along the edge of a sandstone cliff, maybe about 30 yards above me and 200 yards out. I sat down amid a tangle of fallen timber and used a turkey call to mimic the soft clucks of a hen.

Almost as soon as I did, the tom jumped off the cliff and took flight. He flapped his wings maybe six times and soared right over my head. Turkeys are not graceful fliers, nor are they graceful landers. This one crashed through the limbs of a ponderosa pine and then thudded to the ground on the timbered slope of a deep ravine off to my left. I turned my head in that direction and kept on clucking. I was hopeful that the tom would come back, but after a couple of minutes I hadn't seen or heard a thing. I called some more, but still no turkey appeared.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And then something strange happened. Suddenly, someone sighed very loudly just behind my right shoulder. I've had coyotes and bobcats come to my turkey call, but this sigh sounded like that of an annoyed person who was slightly out of breath from running up a hill. I turned my head quickly in its direction and noticed a large male black bear standing on its rear feet with its front feet propped up on a log that was leaning against the log that I was leaning against. I'm sure he was hoping to find a nest full of turkey eggs and, if everything went well, to catch the turkey, too. Now he was staring at me with a very inquisitive look in his eye as he struggled to recalibrate his expectations.

The bear interrupted my whirlwind of thoughts and fears with a woof, like the first noise a dog might make when someone knocks at the door. He then ran off through the timber at the casual pace of a jogging human. The sound of the bear's running died away, and the forest returned to its usual crisp and breezy stillness.

I leaned back to wait for my pulse to slow, and sat for maybe five minutes, just breathing and thinking. How weird was it that this bear and I both happened to be hunting turkeys in the same place at the same time? I had that grateful and relieved feeling that you get when you first realize that you're recovering from the flu. Then I heard a turkey gobble, so far away and faint that the sound seemed more like a feeling than an actual noise. I got up to look for it, happy to be alive and walking in this wonderful and ancient world where bears sigh and turkeys gobble.

OVER 2,000 MILES north of Montana, I was camped on the North Slope of Alaska's Brooks Range, about 75 miles south of the Arctic Ocean's Beaufort Sea. I'd been there for a week, waiting for the arrival of caribou. I hadn't intended to stay so long, and I was running low on food.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I'd dragged my canoe nine miles upriver to this place, convinced that I'd find herds of caribou migrating through on their way toward the breeding and wintering grounds in and beyond the mountains to the south. So far all I'd seen was a group of caribou cows and calves headed the opposite way, toward the north. They didn't do me any good, because all I could legally kill were bulls. I was allowed two of them, plenty of meat to get me through a year without having to buy any from a store.

I hadn't taken a good look around that morning, so I walked up to the top of the small rise behind my camp. Stretching to the east and west was a braided and meandering valley, with its small tributaries and oxbow lakes and gravel bars coated in felt-leaf willow and soapberry and locoweed. To the south, about a mile and a half away, a long ridgeline paralleled the valley.

I watched as three cows followed the same northbound route as the small band that had passed through a few days earlier. There was nothing to signify a trail or a path, and I wondered what was guiding them. I walked eastward a quarter of a mile to look into their tracks. I wished that I could pull some kind of shaman's trick to understand where they were going and whether bulls were following them. But instead, the only thing the tracks revealed to me was my own sense of wonder.

I started back toward the rise as a strange fog blew in from the coast. It came so thick and solid that it looked like it would scrape up my tent and carry it away, but then it began to break up into gauzy wisps that drifted over the land like bed sheets caught in the wind. Just as one of these sheets passed by, I looked to the right and watched as a herd of caribou came over the ridgeline and spilled toward me like a landslide of muscle draped in colors of brown and white and gray. Floating above this body was a tangled forest of antler. They were all bulls.

They reached the river within seconds. If they'd kept coming in that same direction, they would have crossed the river and passed right next to me. But instead they turned sharply to the right and ran upstream. I grabbed my rifle and pack and headed off as fast as possible, trying to parallel their route upstream. I ran until my lungs ached, without catching any glimpse of the animals ahead of me. I covered about a mile or so of tundra before I got to another piece of high ground. From up there, I still could not see the bulls on the opposite side of the river. They had vanished. My initial impulse was to keep moving upstream, but then I noticed something about the contours of the land. Across the river, a slight gully led from the hills into the valley floor. It seemed to provide a good avenue of travel down from the high bank. A matching gully, just a little offset, cut down through the bank on my side. Between the gullies, the valley floor was not as thickly packed with willow as the rest of it was.

I entered the gully and followed it down into the river valley. It terminated at a dry stream channel that was as wide as a driveway. I could see a hundred yards in each direction, upstream and downstream, but only about 30 yards in the direction that I hoped the caribou would come from. I hid myself behind a clump of willows, laid out my backpack, and positioned the barrel of my rifle across the pack for support.

MINUTES PASSED AND nothing happened. Then more minutes passed and still nothing happened. I got a sinking feeling in my gut. The river valley was only so wide, and the caribou had been moving fast. They should have come through already. I thought about racing upriver as a last-ditch effort, but it was too late for that. If they'd run that way, they were long gone by now. After another minute I stood up to try to get a look across the tops of the willows. And then occurred the simple moment that I've been leading up to, the sort of moment that helps me to explain to people why I hunt.

I was hungry in the wilderness and here came a few tons' worth of caribou, 50 yards out and closing fast. In a moment like that, there is no time for emotional dawdling. It is a time for unerring judgment. It is a time for speed, both mental and physical. It is a time for action and precision and discipline. It is a time to do what millions of years' worth of evolution built us to do. And in the act of doing it, you experience the unconfused purity of being a human predator, stripped of everything that is nonessential. In that moment of impending violence and death, you are gifted a beautiful glimpse of life.

From Meat Eater, by Steven Rinella. ©2012 by Steven Rinella. Reprinted by permission of Spiegel & Grau, a division of Random House Publishing Group.

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

The identical twins derailing a French murder trial

The identical twins derailing a French murder trialUnder The Radar Police are unable to tell which suspect’s DNA is on the weapon