Exhibit of the week: The Dawn of Egyptian Art

As early as the 5th century B.C., inhabitants of the Nile valley were working in a distinctively stylized visual language.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Through Aug. 5

For the “longest-running style in the history of art,” no one tops the ancient Egyptians, said Roberta Smith in The New York Times. As early as the 5th century B.C., inhabitants of the Nile valley were working in a distinctively stylized visual language that changed little for millennia and to this day remains “firmly imprinted on human consciousness.” The “sublime, view-shifting” new exhibition at the Met illuminates the origins of this remarkably consistent artistic tradition. Everywhere, animal and human figures offer such inventive, elegant distillations of their real-world counterparts that we see anew that “one of the animating engines” of art is the tension between the abstract and the representational. “With opening acts like these, it is small wonder” that countless generations of Egyptian artists reworked the same ideas over and over again.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

If you notice an absence of pharaohs or pyramids, that’s because this art predates them, said John Zeaman in the Bergen County, N.J., Record. The show’s earliest artifact was created in 4400 B.C.—3,000 years before the reign of Tutankhamen. Old as it is, the work is “far from primitive.” There are no mere pottery shards or rudimentary ax heads here. Instead, expect makeup palettes made of stone but decorated with “jaunty, cartoonish” animal carvings “that might remind you of the wire sculptures of Alexander Calder.” Elsewhere, a freestanding carving of a trotting jackal is most notable for its naturalism, particularly the attention given to the life-like positioning of the figure’s legs. Such works, many excavated from temples and gravesites, suggest that the Egyptian aesthetic evolved not out of “any inability to see or render things more accurately, but out of a striving for elegant forms” that could function symbolically in various rituals.

The show also “whips up a sense of the mysterious,” said N.F. Karlins in Artnet.com. As much as the early Egyptians have been studied, scholars still can only guess at the purposes of much of this work. Among the many beautifully abstracted figures in the exhibit is Bird Woman, a diminutive sculpture on loan from the Brooklyn Museum. Created around 3650 B.C., the figure has a beak-like face but a woman’s body, slightly canted at the hip, with her thin, curled arms raised gracefully above her head. Is she dancing? Is she being transformed into the falcon god Horus? No one knows. For now, like many of the other objects in this “stunning” show, “she remains a lovely mystery.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

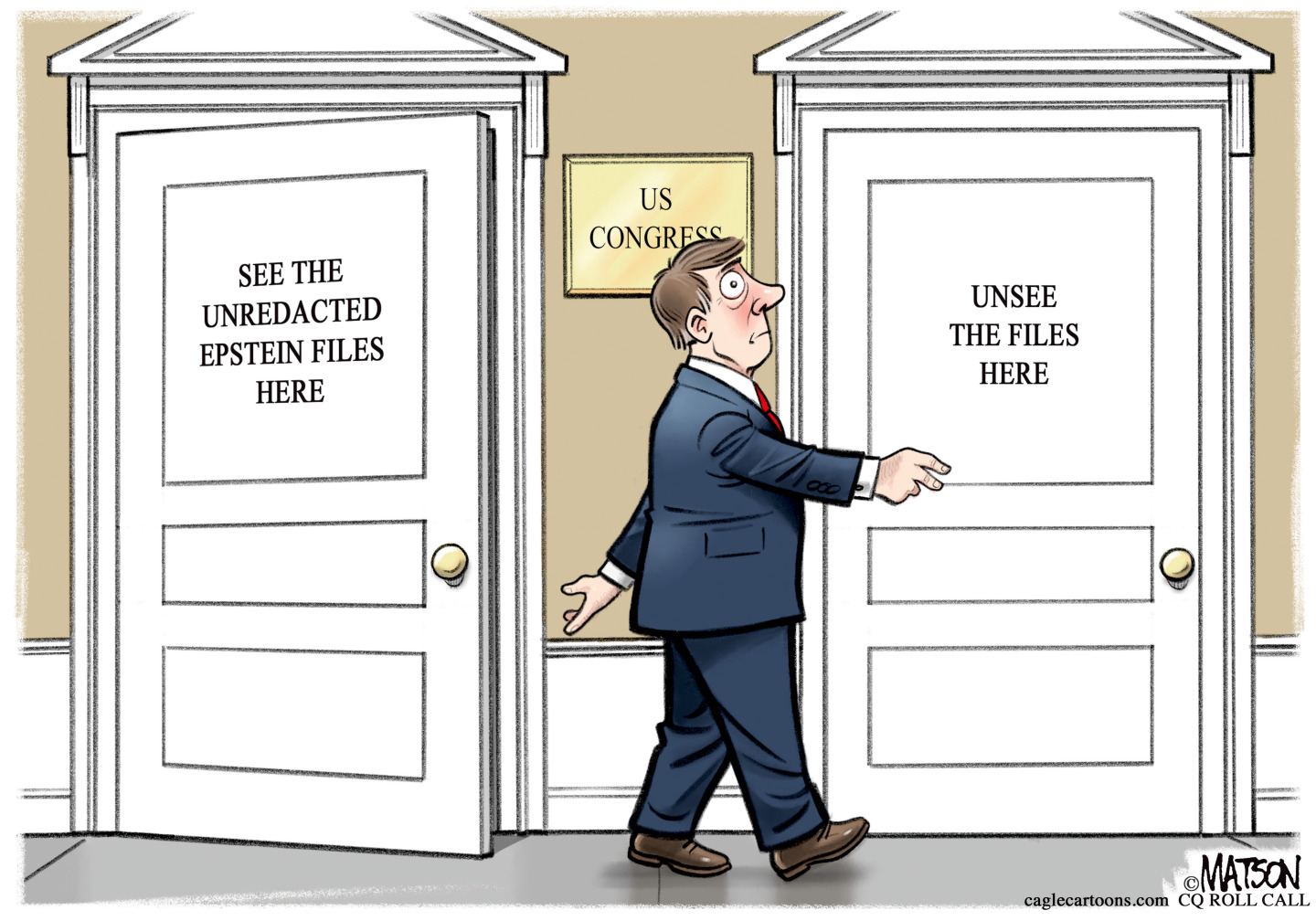

Political cartoons for February 11

Political cartoons for February 11Cartoons Wednesday's political cartoons include erasing Epstein, the national debt, and disease on demand

-

The Week contest: Lubricant larceny

The Week contest: Lubricant larcenyPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas