Coming soon: Self-driving cars?

Long a staple of science fiction, self-driving vehicles that act as robotic chauffeurs could soon become reality

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When will self-driving cars take to the road?

They're already out there. For the past two years, Google has been testing computer-controlled cars in California. Its self-driving Toyota Priuses have so far clocked more than 200,000 miles on busy highways, mountainous roads, and congested city streets with only occasional human intervention. (There are always two human drivers onboard, ready to take the wheel in case of a malfunction). "This car can do 75 mph," said Google engineer Chris Urmson. "It can track pedestrians and cyclists. It understands traffic lights. It can merge at highway speeds." Google isn't the only company road-testing driverless cars — just about every major auto manufacturer has a robo-vehicle in the works. Last year, a robotic BMW drove itself more than 50 miles down Germany's high-speed autobahn. And in 2010, an autonomous Audi completed the twisting 12-mile course at the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb race in Colorado.

How do these cars pilot themselves?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Each Google vehicle has an $80,000 rotating laser range finder on its roof, radars on the front and back bumpers, and a camera fixed near its rearview mirror. Those sensors feed information into the car's central computer, allowing it to simultaneously detect traffic lights, track pedestrians, and watch out for other cars. "We were driving behind an 18-wheeler, and [the radar] saw the vehicles in front of the 18-wheeler — vehicles we could not see with our eye," said Steve Jurvetson, a Google investor and smart-car enthusiast. Google has programmed the car to behave like a model driver. It stops if a pedestrian steps into the road. At a four-way intersection, it gives way to other vehicles in accordance with right-of-way rules. If other cars don't yield as they should, it even eases itself forward to assert its intention to turn.

What's the point of a smart car?

It removes the most unreliable part of the car: the human driver. Every year in the U.S., around 34,000 people die in car accidents, more than 90 percent of which are caused by human error. That toll would almost certainly plummet if we let computers do the driving. A robo-car "can think faster than any mortal driver," said Tom Vanderbilt, author of the book Traffic. "It never panics. It never gets angry. It never even blinks. In short, it is better than human in just about every way." Computer-controlled cars would also be able to safely drive closer together, making better use of the 80 to 90 percent of empty space on our roads and all but eliminating traffic jams.

When will they go on sale?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Engineers and auto executives say they could manufacture self-driving cars around the year 2020. But before they hit dealerships, Google and the auto industry have to overcome some perhaps insurmountable hurdles. Smart cars still lack a key attribute that most human drivers possess: common sense. "Imagine a situation where a box falls on the road in front of you," said John Leonard, a mechanical engineering professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "The system needs to make a split-second decision to either go straight through it or to swerve left or right — which might have worse consequences than just going forward." An experienced driver can assess the safest course of action, but the car's artificial intelligence can't yet handle such unexpected events. And then there are the legal implications of allowing self-driving vehicles on the road.

What are the implications?

No matter how good their guidance systems will be, self-driven cars will inevitably have accidents; even computers are not infallible. So who would be responsible when property and human beings are damaged? The car manufacturer? The tech firm that designed the autopilot software? The human driver, for failing to override the computer in response to danger? Pim van der Jagt, a research chief at Ford, believes that new laws will be needed to deal with these issues, and that cars might need black boxes to record what went wrong during accidents. Even if legal issues can be resolved, it is not clear that most drivers would willingly surrender the wheel to a robo-chauffeur. "The question is going to be not whether we can do autonomous vehicles, but how much autonomy we are willing to put up with as a culture," said Scott Belcher, head of the Intelligent Transportation Society of America. "We don't really like to give up control of our vehicles."

So will people buy them?

Perhaps not, which is why auto manufacturers are focusing current efforts on creating semi-autonomous cars. A new Volvo hatchback, for example, can maintain safe distances in heavy traffic without human intervention. Nissan is working on software that anticipates a driver's next move, adjusting the speed and position of the car going into a turn. And this summer, the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration will put 3,000 test cars equipped with such "driver assist" features on Michigan's roads. But humans are still at the wheel. Robots, at least for the moment, remain backseat drivers.

The car of the future's long history

The idea of the self-driving car is almost as old as the automobile itself. Visitors to General Motors' exhibition at the 1939 World's Fair were shown a vision of the future in which radio-controlled automobiles zipped along highways. Just over a decade later, General Motors and RCA began experimenting with such a system. They embedded radio-transmitting cable into a test track — at a cost of about $100,000 per mile — which communicated instructions to cars driving overhead. In 1958, the company announced that a Chevrolet Impala had successfully made it around the course "without the driver's hands on the steering wheel." But highway officials weren't so taken with the concept. They "screamed at the idea that their new superhighways might be torn up for such cables," BusinessWeek reported later that year, and the project was scrapped.

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

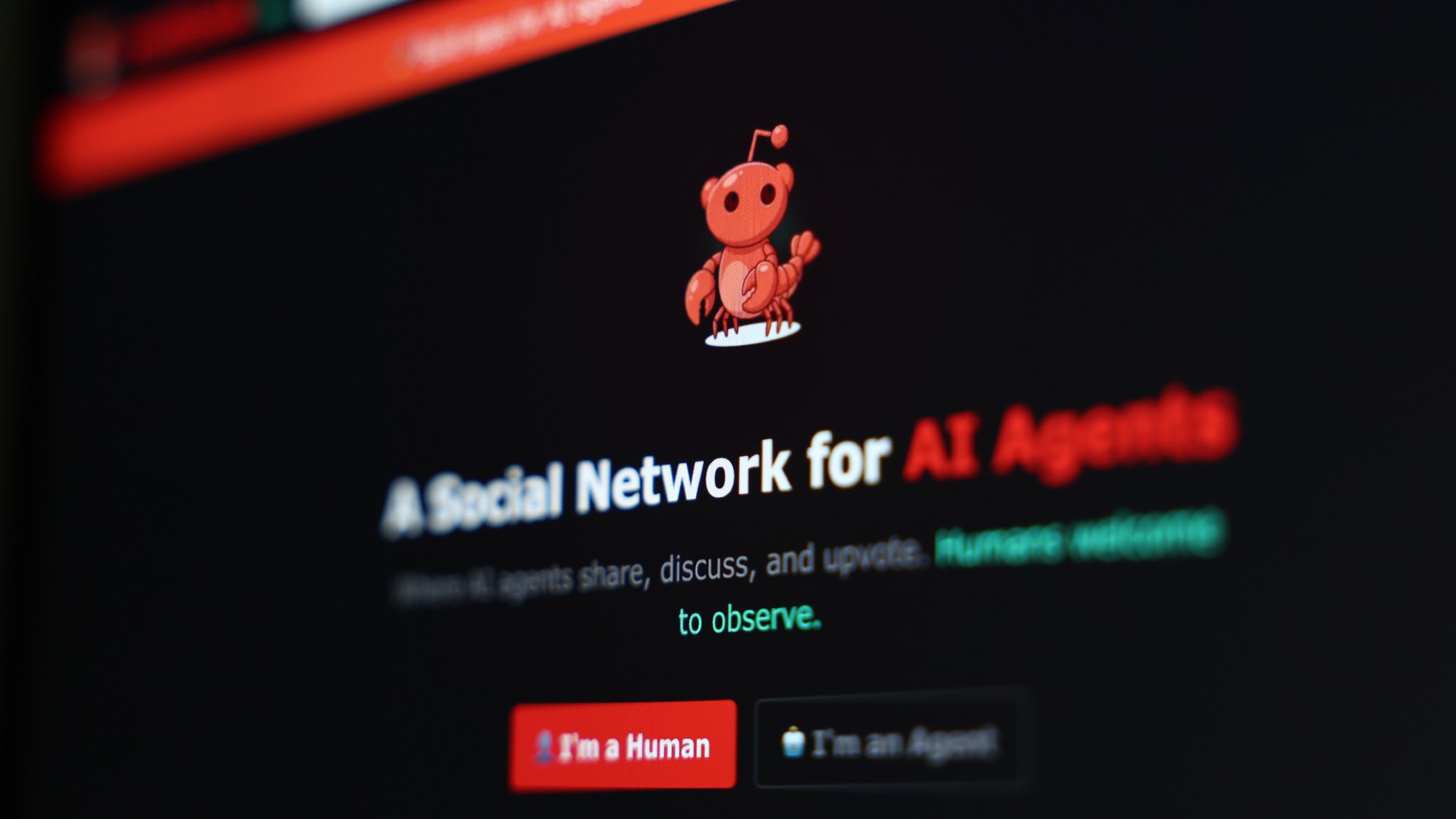

Are AI bots conspiring against us?

Are AI bots conspiring against us?Talking Point Moltbook, the AI social network where humans are banned, may be the tip of the iceberg