Book of the week: Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World by Richard Rhodes

The Pulitzer-winning historian of the atomic age gives the Hollywood star well-deserved credit for her inventiveness and ingenuity.

(Doubleday, $27)

“History has not been kind to Hedy Lamarr,” said David D’Arcy in the San Francisco Chronicle. Despite her ethereal beauty and a Hollywood career that spanned two decades, time has only dimmed the late screen siren’s star. Luckily for her, “Lamarr has an admirer in Richard Rhodes.” In this offbeat new biography, the Pulitzer-winning historian of the atomic age recasts Lamarr as an ingénue possessed of notable ingenuity. Whether or not Lamarr was “the world’s most beautiful woman,” as Louis B. Mayer once asserted, she was certainly among its prettiest inventors. In 1940, Lamarr, along with a collaborator, came up with the design for a radio-controlled torpedo that contained the germ of an enduring communications technology.

This “most unusual book about a Hollywood star” is also an object lesson in the role chance plays in innovation, said Henry Petroski in The Wall Street Journal. Lamarr, who was born Hedwig Kiesler in Austria, in 1913, was “hardly an intellectual.” She dropped out of school at 16 to become an actress, catching the industry’s attention when she appeared nude in the scandalous 1933 Czech film Ecstasy. But she was cleverer than the typical starlet, and also an “indefatigable tinkerer.” Howard Hughes recognized her as a kindred spirit, and tried to help her with one of her ideas—a “bouillon” cube that would fizz in water to create a Coca-Cola–like beverage. But it would be another chance connection, with avant-garde composer George Antheil, that allowed Lamarr to turn her most intriguing concept into something lasting.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Lamarr had ideas but lacked “know-how,” said Sam Kean in Slate.com. Antheil supplied it. While chatting with Antheil about how to aid the war effort, she tossed out the idea of a radio-guided torpedo that could avoid enemy jamming by hopping frequencies in synchronized patterns. Antheil devised the schematics, and the duo received a patent in 1942. Though the Navy initially rejected the technology, it was used during 1962’s Cuban Missile Crisis, and a version of frequency hopping today enables cellphones, Wi-Fi, and GPS to operate without interference. Lamarr, who died in 2000, “felt cheated of credit for these developments,” but Rhodes’s fond portrayal of her as a willful, tireless woman suggests that her own life was her most incredible invention.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

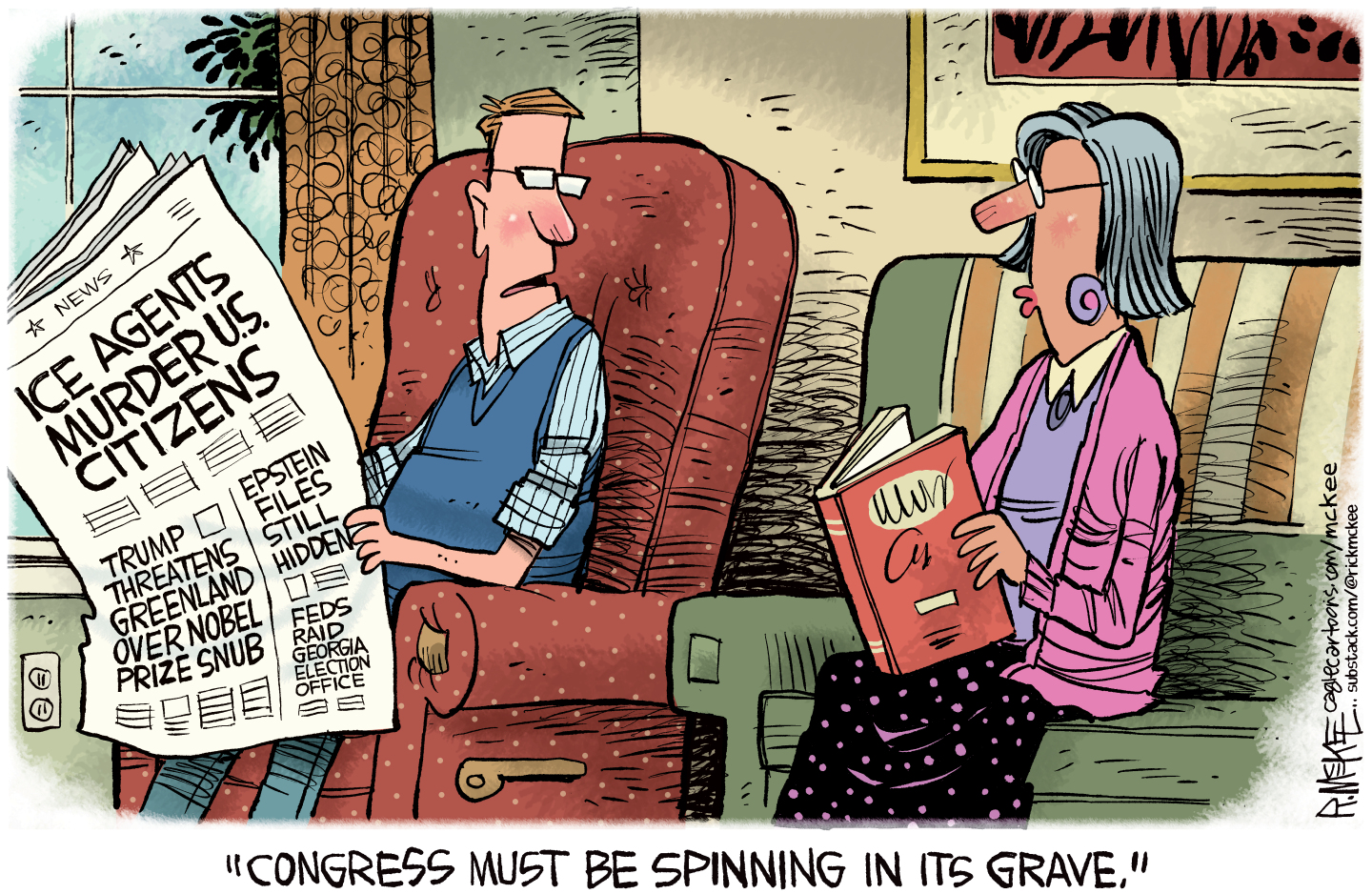

31 political cartoons for January 2026

31 political cartoons for January 2026Cartoons Editorial cartoonists take on Donald Trump, ICE, the World Economic Forum in Davos, Greenland and more

-

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

Also of interest...in picture books for grown-ups

feature How About Never—Is Never Good for You?; The Undertaking of Lily Chen; Meanwhile, in San Francisco; The Portlandia Activity Book

-

Author of the week: Karen Russell

feature Karen Russell could use a rest.

-

The Double Life of Paul de Man by Evelyn Barish

feature Evelyn Barish “has an amazing tale to tell” about the Belgian-born intellectual who enthralled a generation of students and academic colleagues.

-

Book of the week: Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt by Michael Lewis

feature Michael Lewis's description of how high-frequency traders use lightning-fast computers to their advantage is “guaranteed to make blood boil.”

-

Also of interest...in creative rebellion

feature A Man Called Destruction; Rebel Music; American Fun; The Scarlet Sisters

-

Author of the week: Susanna Kaysen

feature For a famous memoirist, Susanna Kaysen is highly ambivalent about sharing details about her life.

-

You Must Remember This: Life and Style in Hollywood’s Golden Age by Robert Wagner

feature Robert Wagner “seems to have known anybody who was anybody in Hollywood.”

-

Book of the week: Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson’s Lost Pacific Empire by Peter Stark

feature The tale of Astoria’s rise and fall turns out to be “as exciting as anything in American history.”