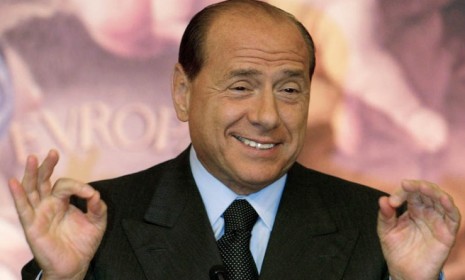

The rise and fall of Silvio Berlusconi

The era of Berlusconi, Italy's longest-serving postwar prime minister, is finally over. Will Italy ever recover?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How did he get to the top?

By leveraging a roguish charm and a gift for demagoguery with great wealth and influence. Berlusconi started out his career as a crooner on cruise ships, before getting a law degree and starting a local cable TV company. He eventually grew that company into Italy's biggest media empire. Along the way, he bought a soccer team, AC Milan, and then founded a political party he called Forza Italia (Go Italy), after a popular fan chant for the national team. When vast bribery scandals in the early 1990s swept away the parties that had dominated the country's politics, many Italians saw Berlusconi as the perfect antidote to corruption: an independent, billionaire businessman who couldn't be bought. But his first stint as prime minister, beginning in May 1994, lasted less than a year before he was hit with fraud charges too. That was just the first of dozens of scandals that have marked his career.

What has he been accused of?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Even before being elected to his second term as prime minister, in 2001, Berlusconi was under investigation for money laundering, association with the Mafia, tax evasion, and bribing judges and financial regulators. Once in office, he applied pressure to downgrade charges, and even to rewrite laws he'd violated. He avoided punishment for using an illegal slush fund to buy a soccer star for AC Milan, for example, by pushing through a 2002 law partly decriminalizing false accounting. Berlusconi has long maintained that he is being picked on by leftist prosecutors. "I am the Jesus Christ of politics," he once said. "I am the most legally persecuted man of all time." He also claims political enemies have tried to create scandals out of his healthy interest in women.

How many sex scandals have there been?

Too many to count. "It's better to like beautiful girls than to be gay," Berlusconi once declared. He is notorious for appointing models and showgirls — and even his dental hygienist — to political positions, and for staging orgies at his various villas. Two years ago, his second wife filed for divorce after he began spending time with an 18-year-old girl who called him "Papi" ("Daddy"). After that came revelations of his "bunga bunga" parties, which he apparently adopted from his pal, the late Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi. Witnesses said "bunga bungas" featured Berlusconi sitting on a throne-like chair as young women dressed in nurse and police uniforms stripped and danced around him; Berlusconi would then allegedly select a few "winners" to join him in bed. He's now awaiting trial (see box) on charges that he paid for sex with an underage prostitute, Karima El Mahroug, and then tried to get her off a subsequent theft charge by falsely telling police the case would cause a diplomatic rift with Egypt.

Why did Italy keep electing him?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As embarrassing as Berlusconi has been to Italy's elites, he retained the grudging admiration of many working-class Italians, who identified with his love of soccer, envied his sex life, and saw him as an authentic man of the people. "The average Italian saw himself as Berlusconi, only poorer," newspaper columnist Massimo Gramellini told The New York Times. Berlusconi — whose nickname, "Il Cavaliere,'' means "The Knight'' — further secured his power by buying the loyalty of other politicians and powerbrokers. "The system he has built has the features of a lordly court: A signore sits at the center, surrounded by a large number of courtesans and servants who owe him their power, their wealth, and their fame," said Princeton political scientist Maurizio Viroli. And as Italy's biggest media tycoon, Berlusconi was able to suppress unfavorable news and comment. He owns three national TV networks, a major newspaper, a top newsmagazine, a publishing house, and the country's largest media buyer. As prime minister, he also had indirect control over state television and radio. Last year, wiretaps caught him chewing out a state broadcasting regulator for airing shows examining his alleged Mafia links. "You might expect this kind of [media] concentration in Turkmenistan or Iran," said Domenico Affinito of Reporters Without Borders. "But it shouldn't take place in a country like Italy."

Is Italy's dire economy his fault?

To some extent — but mostly because of what he didn't do. In 2001 Berlusconi inherited an economy crying out for reform: The tax system was a mess, tax evasion was rampant, and the welfare system was unsustainable. But he ignored the economy to concentrate on passing laws that favored his media empire and protected him from prosecution. Productivity fell, but wages remained high. Italy's GDP began to drop, and the budget deficit and national debt ballooned. By this year, Italy ranked below Belarus and Mongolia in the World Bank's business index. Yet even this summer, in preparing an austerity budget desperately needed to stave off crisis, Berlusconi tried to slip in a measure that would have let defendants avoid paying court-ordered settlements for years — saving his company hundreds of millions of dollars. As journalist Curzio Maltese put it, "Berlusconi never fails to live up to our worst expectations."

The charges he still faces

Out of office, Berlusconi faces three trials he no longer has the means to evade. The biggest is the Mahroug case, in which he's accused of sex with an underage prostitute and abuse of power. Berlusconi didn't manage to pass a law limiting the use of wiretaps, which would have rendered inadmissible some of the more sordid evidence, including phone conversations in which he talks of "doing eight girls." Then there's the charge that he bribed his former lawyer with $600,000 to perjure himself in court; Berlusconi tried to pass a law shortening the statute of limitations so that case would be thrown out. A third case involves tax fraud and false accounting in his company, Mediaset. Still, the 75-year-old needn't worry. In his previous term, he passed a law allowing most criminals older than 70 to avoid jail time.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

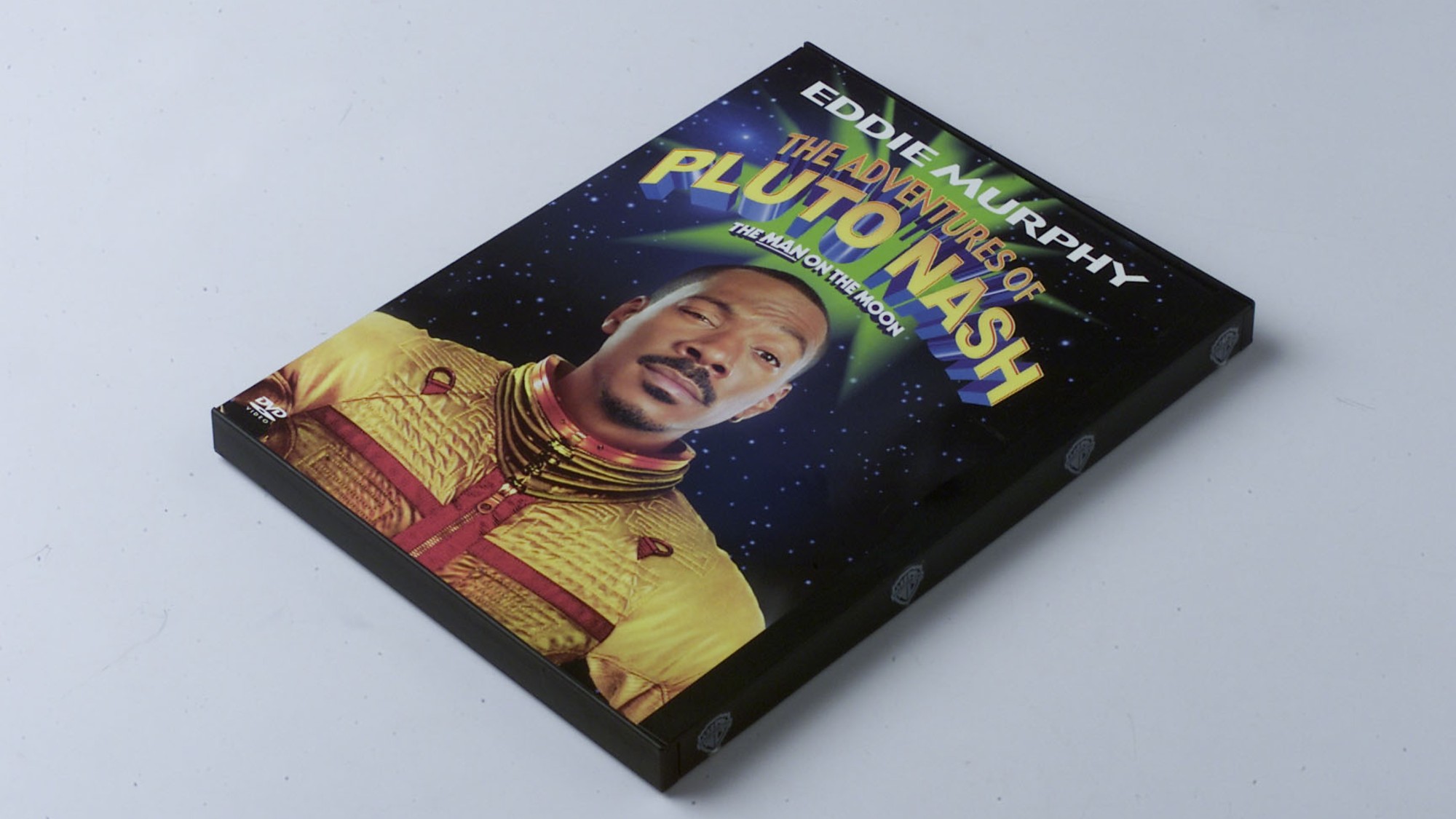

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

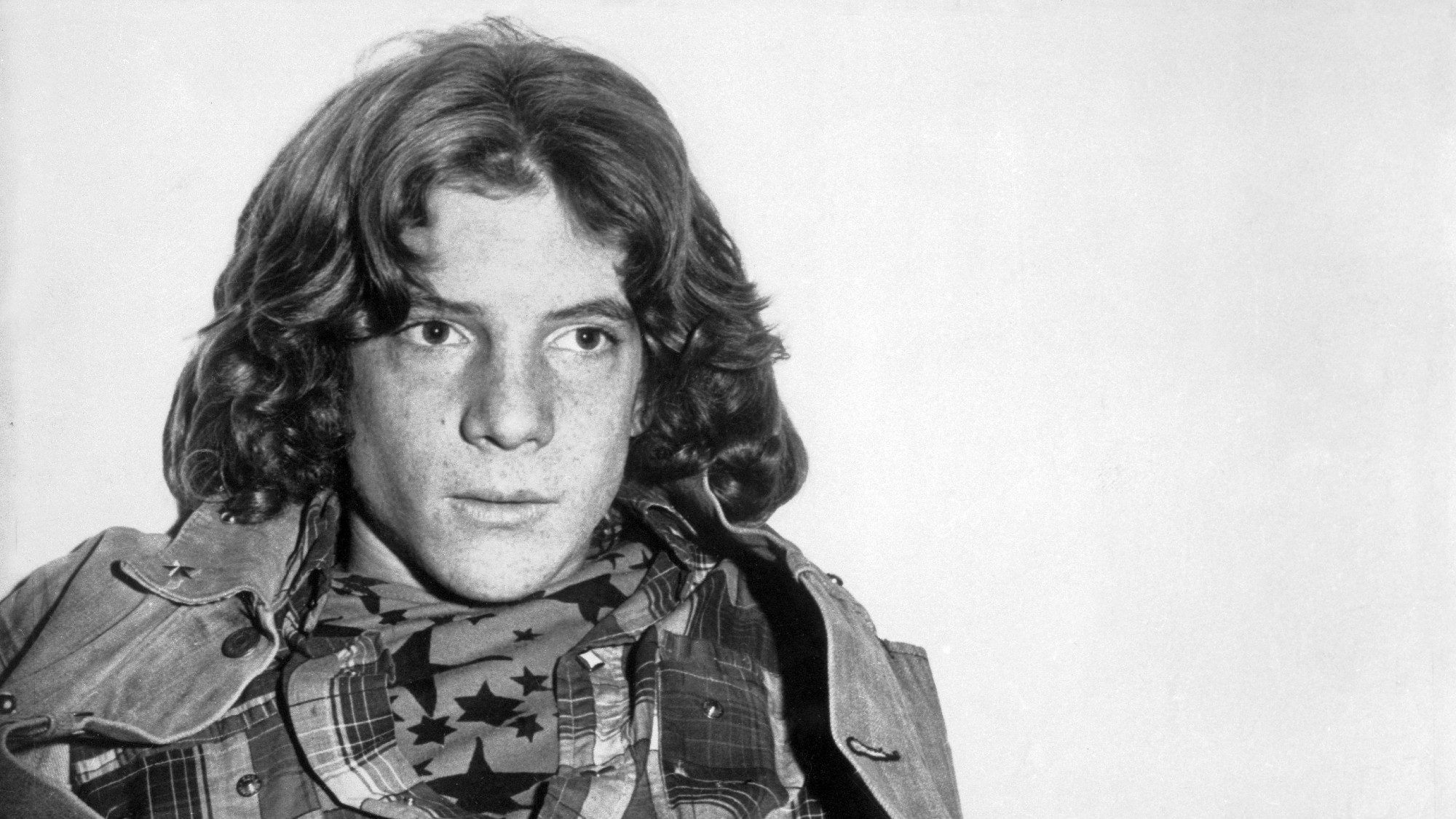

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern history

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern historyin depth The taking of Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is the latest in a long string of high-profile kidnappings