George Harrison: The Beatle who hated fame

After the band broke up, says Brian Hiatt, Harrison sought peace, order, and human connection

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

GEORGE HARRISON WASN'T really "the quiet Beatle," said his friend and Traveling Wilburys bandmate Tom Petty. "He never shut up. He was the best hang you could imagine." To those who knew Harrison well, he was also the most stubborn Beatle, the least showbizzy, even less in thrall to the band's myth than John Lennon. Harrison was fond of repeating a phrase he attributed to Mahatma Gandhi, "Create and preserve the image of your choice," which is odd, because his choice seemed to be no image at all. He was an escape artist, forever evading labels and expectations.

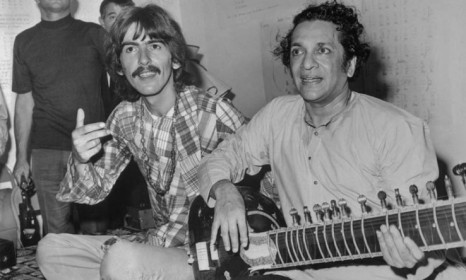

In his time, Harrison challenged Lennon and McCartney's songwriting primacy; almost single-handedly introduced the West to the rest of the world's music through his friendship with sitar master Ravi Shankar; became the first person to make rock 'n' roll a vehicle for both unabashed spiritual expression and, with the Concert for Bangladesh, large-scale philanthropy; had the most Hollywood success of any Beatle, producing movies including Monty Python's Life of Brian; and belied a reputation as a recluse by touring with Eric Clapton and putting together the Wilburys, a band that was as much social club as supergroup.

As Martin Scorsese's two-part HBO documentary George Harrison: Living in the Material World makes clear, Harrison had no casual pursuits: He followed his interests in the ukulele, in car racing, in gardening, and especially in meditation and Eastern religion with fierce energy. "George had a really curious mind, and when he got into something, he wanted to know everything," says his widow, Olivia Harrison, in the companion book to the film (published by Abrams). Olivia met George in 1974 and married him four years later. "He had a crazy side, too," she says. "He liked to have fun, you know." Harrison's first wife, Pattie Boyd, described him veering between periods of intense meditation and heavy partying, with no middle ground. "He would meditate for hour after hour," she wrote in her memoir, Wonderful Tonight. "Then, as if the pleasures of the flesh were too hard to resist, he would stop meditating, snort coke, have fun, flirting and partying."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In 1965, Harrison dropped acid, and all at once, he didn't believe in Beatles. "It didn't take long before he realized, 'This isn't it,'" says Olivia. "He realized, 'This is not going to sustain me. It's not going to do it for me.'" Around that time he began to feel physically unsafe in crowds. "With what was going on," he said, "with presidents getting assassinated, the whole magnitude of our fame made me nervous."

Harrison was just 27 when the band broke up.

Beatlemania had left him with something like post-traumatic stress disorder. "If you had 2 million people screaming at you, I think it would take a long time to stop hearing that in your head," says Olivia. "George was not suited to it."

Harrison deepened his friendships with Bob Dylan ("They had a soul connection," Olivia says) and Eric Clapton, and his time with the two solo artists showed him a way forward. As the Beatles imploded, in 1970, he stepped up with the critically acclaimed triple album All Things Must Pass, letting loose a storehouse of songs that had never made it onto Beatles albums.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The next year, at Ravi Shankar's request, Harrison persuaded Clapton, Dylan, and Ringo Starr, among others, to assemble for the Concert for Bangladesh, which set the template for every all-star rock benefit of the next 40 years. The concert was a triumph, but the aftermath was a painful mess, as Harrison's efforts to get the proceeds to refugees bumped against tax codes and bureaucracies.

His marriage was also collapsing. Harrison was drinking too much, partying too hard, sleeping around. "Senses never gratified / Only swelling like a tide / That could drown me in the material world," he sang, wearily, on the title track of his next album, Living in the Material World.

Harrison went out on the road as a solo artist in 1974, but this was his last tour, save for a short 1991 Japan jaunt. With lengthy Shankar sets opening the show, and his refusal to play familiar Beatles songs (he'd shout his way through halfhearted versions of "Something"), the reviews were brutal. Harrison was unnerved by the rowdy crowds and his hard-partying backup band — it didn't feel like his world anymore. "George talked a lot about his nervous system, that he just didn't want to hear loud noise anymore," says Olivia, who began dating him the year of the tour. "He didn't want to be startled. He didn't want to be stressed."

Harrison would go on to release seven more solo albums, but he became progressively less interested in a conventional career arc. "George wasn't seeking a career," says Petty. "He didn't really have a manager or an agent. He was doing what he wanted. I don't think he valued rock stardom at all."

His relationship with Olivia centered him, and he eased back on the partying. Harrison was ecstatic when the couple had their only child, Dhani, in 1978. His advice to his son was to "be happy and meditate," says Dhani, who grew up in Friar Park, the 120-room mansion in the English countryside that Harrison purchased in 1970. The property was beautiful and mysterious, with caves, gargoyles, waterfalls, and stained glass installed by Sir Frank Crisp, an eccentric millionaire who'd owned it until his death, in 1919. Harrison turned his energies to restoring the 35-acre property's gardens, which had fallen into disrepair.

AS A SMALL boy, Dhani says, "I was pretty sure he was just a gardener," a reasonable conclusion since Harrison would work 12-hour days planting trees and flowers. "Being a gardener and not hanging out with anyone and just being home, that was pretty rock 'n' roll, you know?" says Dhani.

After a five-year gap between albums, Harrison enlisted producer Jeff Lynne for 1987's Cloud Nine, which won him a

No. 1 hit with "Got My Mind Set on You," a rollicking cover of a '60s obscurity. More important, a session to record a B side — a casual collaboration with Lynne, Dylan, Petty, and Roy Orbison — led him to the Traveling Wilburys, the post-Beatles project he enjoyed most.

He reveled in being in a band again, not to mention collaborating with Dylan, his friend and hero. The Wilburys recorded two albums (Dhani remembers hanging with Jakob Dylan and playing Duck Hunt on his Nintendo while the band worked on the second one downstairs), but never managed a live show. "Every time George had a joint and a few beers, he would start talking about touring," says Petty. "I think once or twice we even had serious talks about it, but nobody would really commit to it." A third Wilburys album was always a possibility. "We never thought we were gonna run out of time," says Petty.

Instead, after a quick, 13-date tour of Japan with Clapton in 1991, Harrison became a gardener again. "He didn't want to have any obligations," says Olivia. He kept writing and recording songs in his home studio, but turned down offers to appear on awards shows, or to do almost anything. "I've just let go of all of that," he said. "I don't care about records, about films, about being on television, or all that stuff."

In 1997, he was diagnosed with throat cancer, and underwent radiation treatment. Two years later, a mentally deranged man somehow made his way into Friar Park, and in a horrific, prolonged tussle, stabbed Harrison through a lung before Olivia subdued him. Harrison made a full recovery, but Dhani believes the injuries weakened his father as he subsequently battled lung cancer. The disease spread to his brain, and after a long fight, George Harrison died on Nov. 29, 2001. Olivia is convinced that the hospital room filled with a glowing light as his soul left his body. "He would say, 'Look, we're not these bodies, let's not get hung up on that,'" says Petty, who has practiced meditation ever since his friend introduced him to it. "George would say, 'I just want to prepare myself so I go the right way, and go to the right place.'" He pauses, and laughs. "I'm sure he's got that worked out."

This summer, Dhani Harrison, now 33, returned to Friar Park and gazed out at the garden for a long while. It had never looked better — the trees his father planted had finally grown. "He's probably laughing at me," says Dhani, "saying, 'That's what it's supposed to look like.' You don't build a garden for yourself, right now — you build a garden for future generations. My father definitely had a long view."

By Brian Hiatt. ©2011 Rolling Stone. First published in Rolling Stone. Distributed by Tribune Media Services.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown