The NFL's human sacrifice

Despite rising concern about brain damage, says Paul Solotaroff, linebacker James Harrison hits hard and high

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

AT HIS HOME in tony Scottsdale, Ariz., James Harrison disappears down the hall to get dressed. The Pittsburgh Steelers defenseman is remarkably short for a bull-rush linebacker, barely 6 feet without socks and cleats, but marvelously carved for a man of 250 pounds. He comes back in a Nike tee and black mesh shorts that cover his shins. It's the getup he'll sport for the next three days, wearing it to steak houses, where men in Brioni stare at him in pique, and to jewel-box bistros, where ladies who lunch glower at him over lobster salad. Harrison makes just under $9 million a year and has closets full of handmade, brightly colored suits that he wears when the mood arises. But in lily-white Scottsdale, he couldn't care less about the feelings of the local swells or their custom of donning socks to dine in public. My world, my terms, his outfit announces.

Harrison is the scourge of the National Football League's vexed campaign to check concussive tackles. He is the man who seized Vince Young and dunked the Titans quarterback, all 230 pounds of him, headfirst into the turf like a cruller. This is the man who knocked two Cleveland Browns cold in the span of seven minutes last year, and then baited NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell with his postgame comments, saying he liked to "hurt" opponents.

In Arizona, he is up at first light six days a week, running in hot sand pits and doing backward hurdles after giant leg-press sets. But he is back home by 10 a.m., and that leaves the rest of the day to text and tweet — and seethe over last season's insults. The fines, the flags, his branding as a thug: They try his soul long after the fact, trailing him to this posh but desolate place, where even the air burns and crackles.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"My rep is James Harrison, mean son of a bitch who loves hitting the hell out of people," he says. "But up until last year, there was no word of me being dirty — till Roger Goodell, who's a crook and a puppet, said I was the dirtiest player in the league. If that man was on fire and I had to piss to put him out, I wouldn't do it. I hate him and will never respect him." When he's not ranting, which he does much of the time, Harrison has timely things to say about violence in the NFL. And he will consider, however tersely, the effect of all those hits upon himself. And that, more than anything — more than the grudges, the name-calling — makes Harrison worth listening to.

AS FAR BACK as 1960, when Chuck Bednarik, the cement-mixer linebacker of the Philadelphia Eagles, almost beheaded New York Giants flanker Frank Gifford with a blindside shot at midfield, we've indulged a certain hypocrisy regarding pro football's gilded mayhem. We know that players we've loved and lived through are damaged by the collisions, but we don't wring our hands or click the games off, as we've largely done with boxing. Lately, though, it's gotten a lot harder to ignore the fallen or to pretend that they bounce back up. The 2010 season shattered all records for on-field concussions and season-ending shears of soft tissue, including 261 documented concussions, or almost 30 percent more than in 2008. One weekend last October, dubbed "Black-and-Blue Sunday," there were 11 men concussed, the same day that Harrison iced the two Browns, though neither hit was flagged by officials nor looked, through the prism of slow-motion replay, like a deliberate attempt to injure. Nonetheless, the league had a riot on its hands. The football press erupted that week in righteous indignation, screaming, "Something must be done!" Harrison, who had never been fined more than $5,000, was charged $75,000 for his knockout hit on Cleveland receiver Mohamed Massaquoi.

Football as Harrison plays it has always been a crucible of force on force, big men bleeding for every yard, with the winners being the ones going the extra step: hitting harder, training longer, dying younger. The game lives by a code in which honor and pain are words that describe the same thing, and while the league — belatedly — is thinking long and hard about how to protect its players, there is no protecting them from themselves, at least by Harrison's lights. "I get dinged about three times a year and don't know where I am for a little minute. But unless I'm asleep, you're not getting me out of the game, and most guys feel the same way. If a guy has a choice of hitting me high or low, hit me in the head and I'll pay your fine. Just don't hit me in the knee, 'cause that's life-threatening. How'm I going to feed my family if I can't run?"

If you've been wondering why players hit higher than they used to, there's as good a reason as any. A concussion is, on average, a one-game injury, according to numbers kept by the league. But a torn medial collateral ligament is a season or more — and the NFL is the only major sport that refuses to guarantee contracts. Stack up the far-off prospect of brain damage against a voided $30 million, and most players will roll the dice. "Guys tackle high now and are taught that way. We're not gonna change that up because you say so," says James Farrior, the Steelers' inside linebacker, a two-time Pro Bowler himself. If you're aiming higher, though, you're leading with your head, which courts the risk of helmet-to-helmet hits. But the Steelers don't want their players letting the runner have forward progress. Says Harrison: "That's what we're told by Coach LeBeau — blow through the guy, not to him. When the fines came down, he said, 'Don't change a damn thing. You're doing it the way we do it on this team.'"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

For the past four years, Harrison has embodied that ethos. He was the Defensive Player of the Year in 2008, when his numbers across the board (16 sacks, 101 tackles, and seven forced fumbles) were freak-show good, and he might have won the trophy again last year if his back hadn't seized and cost him power. He's a half foot shorter than most of the tackles trying to block him, but gets tremendous leverage from his hips and quads, a drivetrain like no one else his size. "He's weight-room strong but superstrong in games, a lower body with insane amounts of pop," says Steve Saunders of Power Train Sports, Harrison's fitness guru in Pittsburgh. "Combine that with his upper body — he benches 500, close-grip — and James can move guys anywhere he wants."

ODDLY, HE WAS the quiet one of six brothers and seven sisters, speaking to almost no one outside the family and sleeping with his parents till he was 12. "James was my baby, a mama's boy," says Mildred Harrison, who with her husband, James Sr., a retired trucker, still lives in the house, in Akron, where she raised her kids on a diet of love and sternness. Wielding a belt that she called Black Beauty — "My mom would come to school and whip us in class," says Harrison — she successfully saw each of her progeny through high school and on to stable jobs and college. Most of them settled within five or six blocks of her and travel, en masse, to Harrison's home games. "I haven't missed one in eight years," she says.

After he started as a pro, in 2002, Harrison was cut four times in the span of two years, and he was ready to chuck the game and set about earning his trucker's license. Then he caught a break. Clark Haggans, a Steelers linebacker, broke a hand while lifting weights, and Harrison got one last invite, in 2004. He came to camp burning to learn the blitzes and stayed up nights turning flash cards over and scribbling play cues on his wristbands. Harrison made the team as a special-teams monster, crushing kickoff returners with pile-driving shots you have to YouTube. But the Steelers made him wait three years to start and thought so little of his long-term prospects that they took linebackers with their top two picks that spring. Properly insulted, Harrison came out blazing. He was named the team MVP that '07 season and the league's best defender the following year, and became the highest-paid linebacker in history in '09. He hasn't looked back since, except in anger. "There's a river," he reckons, "of people that want to cheat me."

When Harrison gets going on one of these runs, there's no telling where he'll end up. He can be biting (and baiting) on a wide range of subjects: Ask him, at your peril, his views on gay marriage, which make Glenn Beck sound squishy; his position on spanking (he's for it, and how; his two young sons should try handing down fines); and if you ever get him going on gun control, better whip out your Kevlar notepad. But then, without prompting, he'll turn on a dime and offer a sober position on player safety, saying the league should trim the season to 14 games; begin off-season training activities in May, not March; and cut training camp down to just a couple of weeks of one-a-day practices, not two. That way, he says, "we're not bangin' heads so much in August; that's where the brain trauma comes from."

He's right about that. And Harrison, for all his bluster, isn't heedless of the facts or the effect of all those hits on his long-range health. "When you hit a dude hard, you feel it, too, and the Steelers go at play-to-die speeds. But if, God forbid, I wind up having brain damage, so be it."

HE HAS THREE years left on his handsome contract, and if he's lucky enough, he says, to finish that out, he'll quit and turn to his new passion: real estate. With his partner, a veteran developer named Tom Janidas, Harrison is building off-campus housing at two colleges in West Virginia, and has already put together an impressive portfolio, with many more units to come. Harrison talks avidly about future projects and amassing his own fortune, then buying a jet to show his sons the world, taking them "wherever they have running water."

But for now, at least, Harrison's probably said enough. He doesn't need invective to make his point that he plays a savage game and that any attempts to childproof the sport will be met with fierce resistance. The players are so big now, so fast and so fit, that no fines, however stiff, or threats of suspension can keep them from hurting one another. At some point in the future, the keepers of the kingdom will have a decision to make: either drastically rewrite the sport's DNA — outlaw tackling above the waist, say, and impose weight limits — or watch it die in flames like ancient Rome. For now, though, these men are our gladiators, and horrified or not, we throng the coliseums, hoisting two thumbs merrily in the air.

©2011 Men's Journal. First published in Men's Journal. All rights reserved. Distributed by Tribune Media Services.

-

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’the week recommends The pasta you know and love. But ever so much better.

-

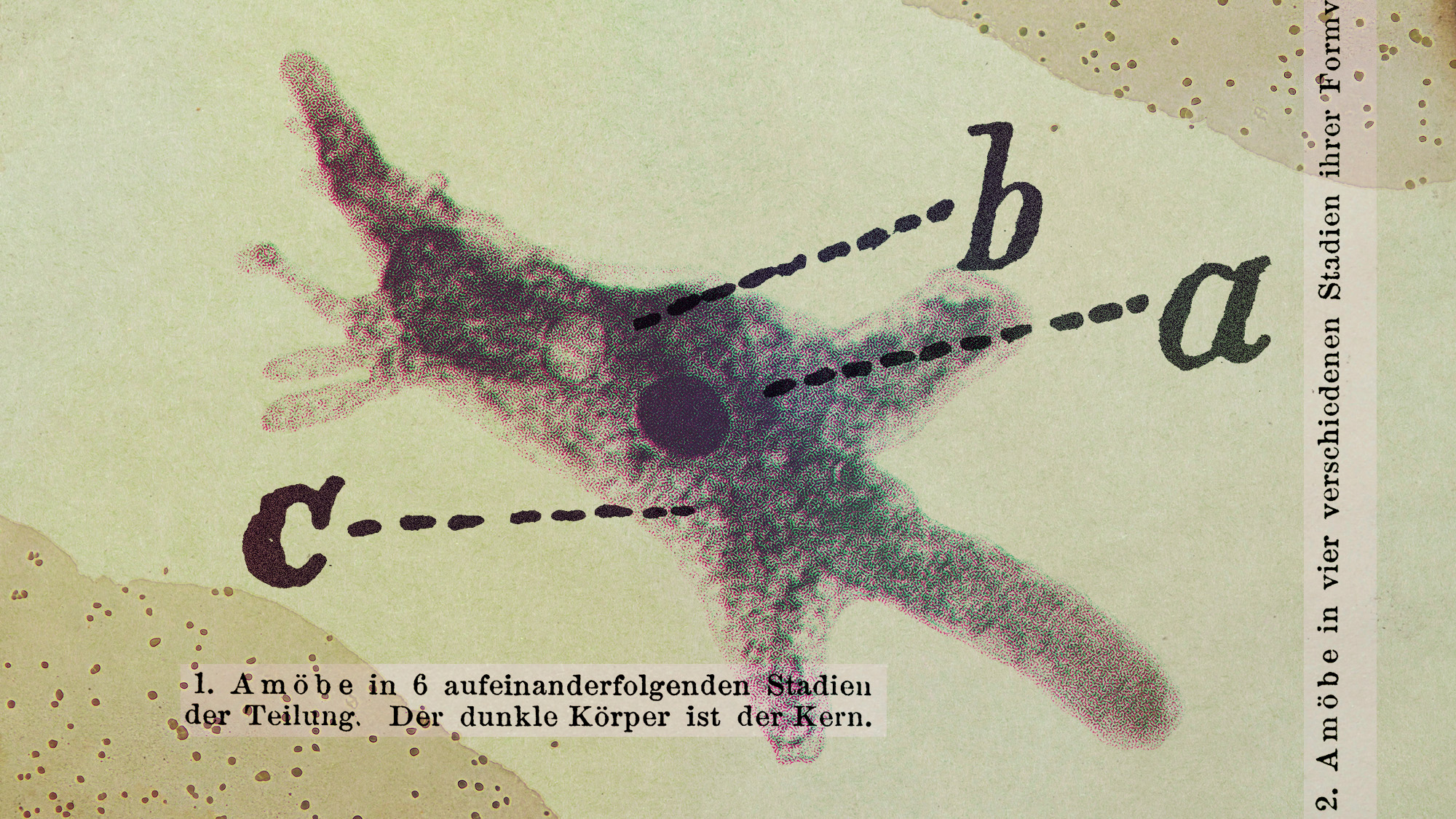

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peace

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peaceUnder the Radar Crowds have turned out on the roads from California to Washington and ‘millions are finding hope in their journey’