America's 'food deserts'

More than 23 million Americans live at least a mile from the nearest supermarket. Is that what's making us fat?

What is a ‘food desert’?

A community in which residents must travel at least a mile to buy fresh meat, dairy products, and vegetables. More precisely, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines a food desert as any census district where at least 20 percent of the inhabitants are below the poverty line and 33 percent live over a mile from the nearest supermarket (or in rural areas, more than 10 miles). Approximately 23.5 million Americans live in a food desert, says the USDA, including vast, rural swaths of West Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky, as well as urban areas like Detroit, Chicago, and New York City. The government believes food deserts are contributing to the obesity epidemic in the U.S., by forcing the rural and urban poor to rely on processed foods and fast food, instead of fresh meat, vegetables, and fruit. Today, more than one third of adult Americans are obese.

Can this trend be reversed?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The government thinks it can, if major supermarkets open stores in blighted areas and stock affordable healthy food options. First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move!” campaign, which aims to reduce childhood obesity, has taken a lead role in this effort, and recently scored a major coup by convincing Walmart, SuperValu, and Walgreens to open or expand 1,500 grocery stores in food deserts. The involvement of large retail firms has “the potential to be a game-changer for kids and communities all across this country,” Obama said. “More parents will have a fresh food retailer right in their community, so they can feed their families the way they want.” But not everyone shares the First Lady’s optimism; in fact, some critics say opening new stores and markets in so-called food deserts will have little or no impact on how people eat.

Why would that be?

First of all, the critics say, the very concept of a food desert may be a mirage. One recent University of Washington study found that only 15 percent of people shop for groceries within their own census areas; most of us, in other words, are accustomed to traveling a few miles to stock our pantries. Critics also point out that the USDA takes only supermarkets into account when deciding whether an area is a food desert. Smaller grocery stores, farmers markets, and roadside stalls aren’t included. Moreover, the vast majority of households (93 percent) in food deserts have access to a car, and can easily drive to grocery stores over a mile from their homes.

So what’s the real problem?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Many people simply like fast food better. A recent University of North Carolina (UNC) study of the eating habits of 5,000 people over 15 years found that living near a supermarket had little impact on whether people had healthy diets. But living close to fast-food outlets did. The real problem, the study found, is the existence of “food swamps,” filled with convenience stores selling calorie-loaded packaged foods, gallon cups of soda, and other sugar-loaded beverages, and fast-food chains peddling burgers, fries, and fried chicken on almost every street corner. That’s no exaggeration: There are now five fast-food restaurants for every supermarket in the U.S.

Why do people choose the ‘bad’ food?

Fast food is generally cheaper, and doesn’t need to be prepared and cooked, so it’s more convenient. Studies have also shown that the huge jolt of fat, salt, and sugar fast food delivers can be almost as addictive as hard drugs (see below). Then there’s the advertising factor: Fast-food companies spend about $4.2 billion a year marketing their products as life’s ultimate rewards, through saliva-producing ads depicting cheese-and-pepperoni-covered pizzas, juicy double cheeseburgers, and steaming French fries.

Can these preferences be changed?

The UNC study suggests using zoning laws to restrict the number of fast-food restaurants in low-income neighborhoods. Los Angeles has already experimented with this approach, having imposed a one-year moratorium on the building of fast-food restaurants over a 32-square-mile area. City officials say the results were successful, and have now imposed permanent zoning restrictions on fast-food chains in the poorer, southern part of the city. “We have already attracted new sit-down restaurants, full-service grocery stores, and healthy food alternatives,” said City Councilwoman Jan Perry. “Ultimately, this action is about providing choices.”

Will people choose healthy food?

Not necessarily. Many Americans have little experience eating or preparing broccoli, asparagus, and other produce; in fact, only 26 percent of the nation’s adults now eat three servings of vegetables a day. The poor, in particular, have become so accustomed to salty packaged foods and sugary beverages that they find fresh food bland, strange, and off-putting. “It’s simplistic thinking that if you put fruits and vegetables there, they’ll buy it,” said Barry Popkin, author of the UNC study. “You have to encourage it, you need advertising, you need support.” Changing Americans’ diets, in other words, won’t be as simple as telling them to eat their peas.

Fast-food junkies

If it sometimes seems that Americans are addicted to fast food, it might be that we actually are. Studies have repeatedly found that the consequences of bingeing on high-calorie, high-fat foods mimic the effects of drug addiction. A recent study by the Scripps Research Institute found that gorging on fast food actually changes the brain’s chemical makeup, making it more difficult to trigger the release of dopamine (aka “the pleasure chemical”). That means fast-food addicts need to eat more and more to feel happy—the same way users of cocaine and other drugs, for example, need to keep upping their dosages to get high. An earlier study, by Princeton University, found that rats who were fed and then withdrawn from a high-fat, high-sugar diet exhibited similar symptoms—chattering teeth and the shakes—to junkies going cold turkey. “Drugs give a bigger effect,” said study author Bart Hoebel, “but it’s essentially the same process.”

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

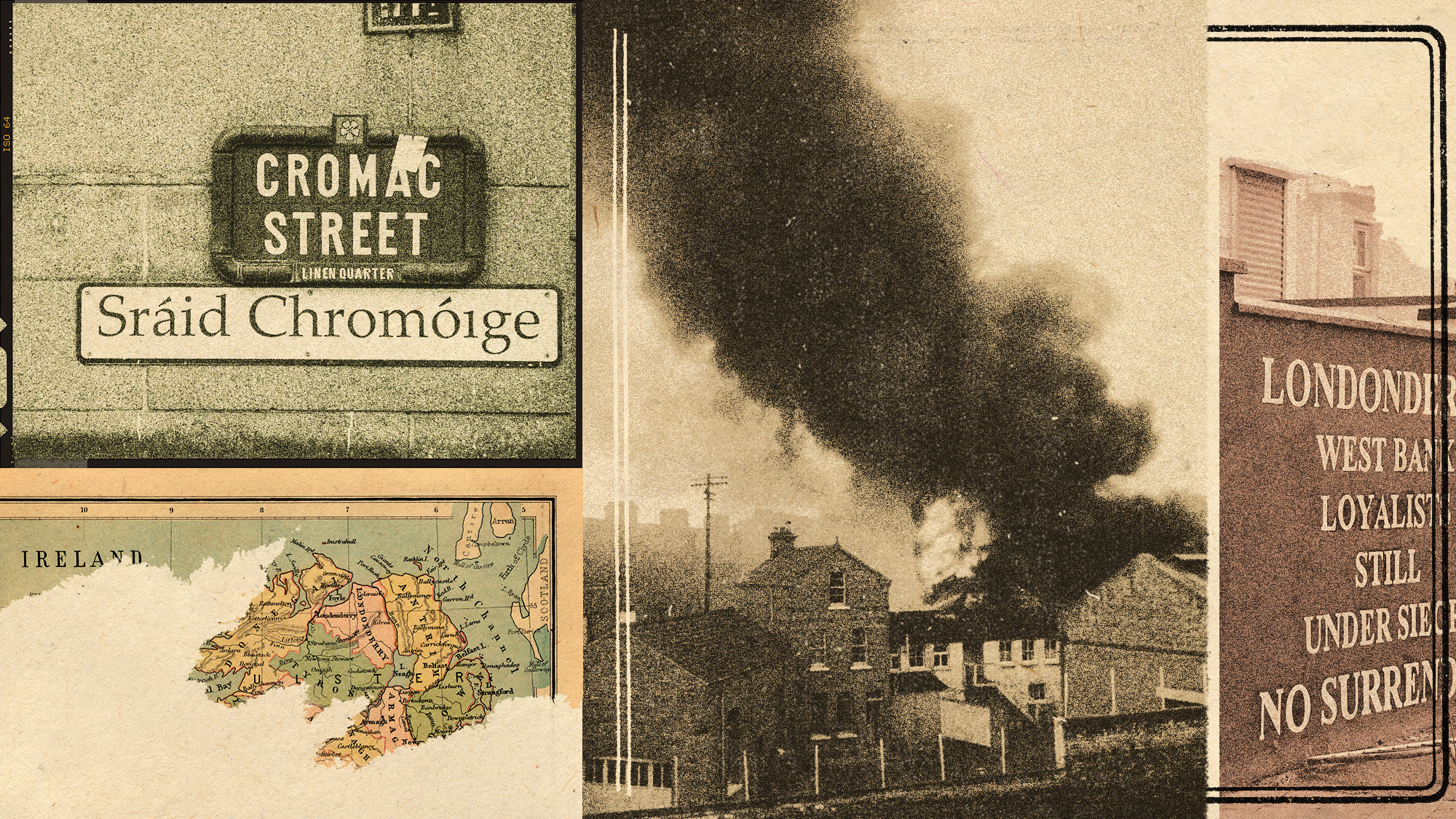

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion