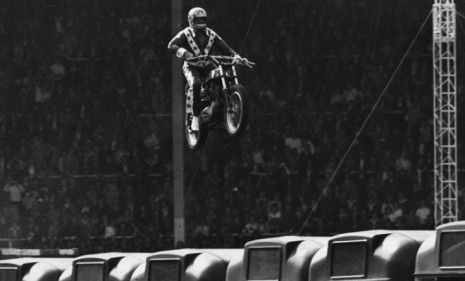

Evel Knievel's 'last' jump

The daredevil badly needed a comeback, says Leigh Montville, so he tried a stunt that was doomed to fail

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

EVEL KNIEVEL ARRIVED in London on May 6, 1975, which gave him almost three weeks to promote his next big jump, at Wembley Stadium. After the Snake River disaster, this would be his triumphant return, and there was no need to hold back.

Knievel might have been unknown in Great Britain, but he was made for the British tabloid press. He spoke only in headlines, dressed only in his flamboyant outfits, carried his cane full of whiskey, drove around in the candy apple red customized Cadillac pickup truck.

Frank Gifford, the former New York Giants running back, famous now as Monday Night Football’s play-by-play man, was the Wide World of Sports broadcaster for the jump. He had become friends with Knievel, spent some time with him beyond the normal ABC meetings. He liked Knievel, liked his style. “He was a little wacko,” Gifford said. “I kind of admired him.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The night before the jump, Knievel asked the 44-year-old Gifford to have dinner with him. They went to a restaurant where Knievel, surrounded by Brits, told his stories, drank straight from the cane, drank an assortment of other drinks that arrived at the table. Dinner was followed by visits to a string of pubs, and more drinks.

The next day, he was a mess. Gifford was with him when he went out to Wembley and took his first look at the ramp and the 13 buses he would attempt to jump. “I can’t do this,” he said. Gifford’s reaction was, “What do you mean you can’t do this? If you can’t do it, then don’t even try. Pull the plug right now.”

“I can’t do that,” Knievel said.

Take a couple of buses out of the line. Easy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

“I can’t do that,” Knievel said. He said that there was not enough room on the takeoff ramp to get up to speed. Not enough speed to clear the buses.

He said that was too bad, but he still would do the jump.

Gifford wanted nothing to do with a stunt that was this risky. He didn’t want to be part of a televised death. Panicked, he searched for Doug Wilson, the producer. He explained his worries. Wilson became worried. They went back to see Knievel at his trailer.

They knocked on the door. No answer. Knocked on the door again. No answer. Opened the door. Knievel was asleep.

Gifford woke him up. Asked how he felt now. Knievel said he was fine. He would find the speed somewhere. The show would take place.

Gifford still wasn’t sure about any of this, still was nervous, but at the appointed time, 20 minutes after 4 on a Monday afternoon in London, he was in his yellow ABC blazer. Knievel was in a new set of leathers, blue, just for Wembley, with enormous white French cuffs. He was doing some wheelies, then his two warm-up trips: down the ski slope, stop; down the ski slope, stop.

“I was talking with him today, and he looked out at the 70,000 people here and said, ‘What does a man have to do to get this many people together?’” Gifford said on television. “I said, ‘Evel, you’re doing it.’”

This was the largest live crowd that ever had seen him perform, the largest by far. This was the crowd that should have been at Snake River, kids and families. The prices ran from $3 to $8 for the show. Affordable. This was his public relations masterpiece.

He came down the ramp on that third trip, after he gave a thumbs-up to let the producers know this was for real, tried to get the speed up to somewhere between 93 and 95 mph, the number he felt would give him a distance of 130 feet, enough to clear the buses.

THE PARABOLA WAS all wrong from the beginning. Too flat. Too short. He came down hard on the front wheel on the plywood safety extension that covered the top of the last two buses. Blam. The 13th bus. The motorcycle bounced high in the air. He was thrown forward. There was a moment, perhaps, when he could have saved himself…he tried to hang on, tried to hang on, tried…but then he was gone. Over the handlebars, flipped, flying, gone. He landed and rolled over and rolled again, and the motorcycle followed him, stalked him, seemed to know what it was doing.

When he stopped rolling, the motorcycle rolled on top of him. “He’s down and he is hurt,” Gifford said on the telecast. “Oh my God.” Knievel’s mechanic, John Hood, was the first one to Knievel. He pulled the motorcycle off Knievel’s legs. Frank Gifford was close behind. Gifford was terrified. He saw a bone sticking out of Knievel’s hand. He saw blood coming from Knievel’s mouth. Gifford thought he not only had been part of a televised death, he was part of a televised death of a friend. The crash was violent and stunning. How could anyone survive? Knievel had almost landed at Gifford’s feet when he finally stopped.

The announcer dropped his microphone and bent down and was only slightly heartened by the fact that Knievel was trying to speak. This would be the daredevil’s dying declaration, possibly his last words. Gifford listened very hard because he wanted to make sure he heard exactly what Knievel said.

“Frank…,” Knievel said. “Yes, Evel,” Gifford said. “Get that broad out of my room,” Knievel said.

The scene that followed was dramatic, melodramatic, serious, yet strange, part B movie, part Oberammergau Passion Play, part Road Runner cartoon. Knievel was shifted carefully to a stretcher, carried toward an ambulance. The crowd was beginning to cheer. He was alive.

Knievel didn’t want to go to the ambulance. He wanted to go to the ramp, wanted to talk to the people. He wanted a microphone. Forget the blood, the bone in his hand. The route was turned toward the ramp. Room was cleared with each step. The microphone was brought close. Knievel asked to be helped up. The process was very slow.

When he finally stood, one arm over the shoulder of promoter John Daly for balance and strength, he made his announcement.

“Ladies and gentlemen of this wonderful country,” he said into the microphone, “I have to tell you that you are the last people in the world who will see me jump. Because I will never, ever, ever jump again. I’m through.”

The reaction from the English crowd was mixed. There were as many boos as there were cheers, a lot of people who thought this was an act. He really wasn’t hurt, couldn’t be hurt. He was up there talking.

The people around him knew differently. He clearly was injured. He was in a lot of pain, winced every time he moved. His hair was everywhere, his face as dirty as if he had come from eight hours in the mines back home in Butte, Mont. He should have been somewhere in the middle of the city now, siren blaring, headed toward an emergency room. He was here. He wanted to walk off the ramp.

Walk off the ramp? Gifford said he should get on the stretcher.

“Help me walk off the ramp,” Knievel said. “I got you, buddy,” Gifford said.

He walked off the ramp. Progress was very slow, Gifford at one side, John Hood at the other side, but he walked. Every time he paused, someone would suggest the stretcher. Every time someone suggested the stretcher, Knievel would plead his case.

“I want to walk out… Please help me out… I want to walk out… Please.

“I want to tell you something, Frank. I don’t know how I got here. I’m hurt awful bad. I walked in, I want to walk out.”

He eventually was put on the stretcher, lifted into the ambulance, taken to the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, a two-hour trip through traffic. He was diagnosed with a broken right hand, a compressed fracture of the fourth and fifth vertebrae in the lower part of his spine, a fractured left pelvis, and a 7¾-inch split in his right pelvis.

Once again, his injuries, as serious as they were, did not match the impact of the pictures of the crash. The dialogue, the words to the crowd, the way he looked—this again was stuff that never had been seen on television. This was more than reality. This was hyper-reality. He looked as if he were dead.

IN THE HOSPITAL, Knievel blamed his “idiot mechanic” and the buses. The American bus was 8 feet wide. The London bus was 8½ feet wide. Six inches per bus, 13 buses, a 6½-foot difference. Give him the extra 6½ feet, and he would have made the jump perfectly. Give him different gears, based on the knowledge that the buses were wider, and he would have made the jump perfectly. The idiot mechanic kept quiet because he was in need of a job, but pointed out a couple of things years later. The first was that Knievel had practiced only once, and that was that time for the press in the parking lot. The second thing was that this was the first time in his life that Knievel ever talked about technical things.

He was not a technical man. He basically used two Harley XR750 bikes for his shows, one bike for wheelies, the other for jumps. The wheelie bike was geared lower, so it was easier for him to flip the front end upward and ride that way. The jumping bike was set up with higher gears for the speed necessary to make the jump.

The miss was no different from any of Knievel’s misses—it was a miscalculation. He had no speedometer on the bike, no tachometer, did no research, nothing. He jumped totally on instinct and feel. His feeling was wrong here.

THE RETIREMENT LASTED three days. The Wide World show wouldn’t be seen until Saturday, and on Thursday, at 5:30 in the morning, Doug Wilson’s phone rang in New York. Wilson had returned home to edit. Knievel told him to make a big edit. Wilson should cut out that whole speech to the crowd. Turned out Knievel didn’t mean it. He wasn’t going to retire. The speech would look stupid. “No, it won’t,” Wilson said. “We’ll say something. People will understand.”

“You can’t run it,” Knievel said. “We’re going to run it,” Wilson said.

Knievel became angry. He threatened to sue Wilson, to sue ABC, to sue everybody concerned if the speech ran.

On Saturday the show ran, the retirement speech ran. The tape was spellbinding. This was something that people did not see in the technology of 1975. This was different. This was exciting. Argue the morality of what this guy did for a living, fine, but admit that this was some kind of show. He walked in, and he was going to walk out. After the flop at Snake River Canyon, this was the rebound of Evel Knievel.

He was in the hospital for 11 days, then back at the Tower Hotel for five more. His wife, Linda, hurried to London along with his kids, Kelly and Robbie. They accompanied him back to New York and then home to Butte, where he was scheduled for three more weeks of bed rest. He said he would return to London in the fall to tackle those buses again.

“You told 70,000 people you were going to retire,” said a reporter at John F. Kennedy Airport. “How can you say now that you’re going back?”

“I don’t care what I say,” Knievel said from the gurney. “The schedule calls for me to jump again in September.”

Excerpted from the recently published Evel by Leigh Montville. ©2011 by Leigh Montville. Reprinted with permission by Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict