5 best novels of the year

These stories — packed with family dysfunction, engaging generational portraits, and cultural critiques — were picked by the nation's top critics as the best fiction of 2010

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this season of "best of" lists, book reviewers and literature lovers are clashing over which novels deserve to be recognized as the best of 2010. Here — based on year-end recommendations from 14 publications, from The New Yorker to Publisher's Weekly — is an aggregated list of the most memorable novels released this year:

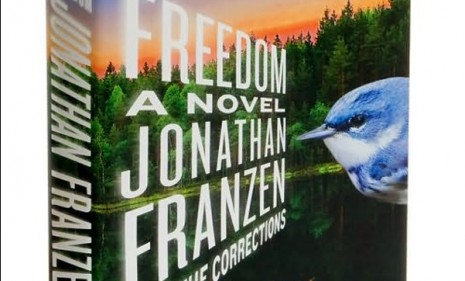

1. Freedom

by Jonathan Franzen

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $28)

Jonathan Franzen's fourth novel is "both a compelling biography of a dysfunctional family and an indelible portrait of our times," said Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times. Through the Berglunds, a middle-class Midwestern family that is both moving up in the world and teetering on the verge of collapse, the first novel from Franzen since 2001's The Corrections captures the "absurdities" of contemporary American life with characters as close to "fully imagined human beings" as a writer can achieve. Like The Corrections, this book is "heavy on psychology and extramarital affairs and earnest speechifying," said Sam Anderson in New York. But the characters are new, and they’re each "so densely rendered" that they enter our lives as if they were friends or neighbors. That trait alone marks Freedom as "a work of total genius."

A caveat: Franzen makes his "average" Americans so small in spirit, said B.R. Myers in The Atlantic, that spending 500 pages with them is a crushing bore.

2. A Visit From the Goon Squad

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

by Jennifer Egan

(Knopf, $26)

"Rarely is the most structurally interesting book of the year also one of the year's most engaging," said Mary Pols in Time. But Jennifer Egan's "hybrid of a novel and short-story collection" defies the odds. The author's "clear-eyed" portrait of a generation embraces an array of voices, with each chapter marking a shift in perspective and chronology, and one chapter even assuming the shape of a PowerPoint presentation. These vignettes produce a decades-long group portrait of several characters — including a sell-out record executive and his kleptomaniac assistant—who mostly came of age in the 1980s and are linked by various ties to the music industry. The book might sound like the kind of "headache-inducing, aren't-I-brilliant tedium that sends readers running to nonfiction," said Ron Charles in The Washington Post. But Egan's stylistic tricks help create "a deeply humane story about growing up and growing old in a culture eroded by technology and marketing."

A caveat: Egan has so much ground to cover, said Dylan Hicks in the Minneapolis Star Tribune, that she sometimes resorts to narrative "shorthand."

3. Room

by Emma Donoghue

(Little, Brown, $25)

In this "emotionally draining" but riveting novel, readers see the world through the eyes of a 5-year-old boy whose entire life has been spent with his mother in an 11-by-11-foot shed, said Liz Raferty in The Boston Globe. Inspired by real-life abduction cases, Irish novelist Emma Donoghue makes young Jack her narrator and his mom a brave woman who's been held for years by a sadistic captor and is shielding her son by leading him to believe that the world outside is unreal. Donoghue's "flawless" storytelling works so well that "Jack's naïveté about his situation alternates between endearing and heartbreaking." Don't be scared away by the "lurid-sounding premise," said Laura Miller in Salon. Room is no twisted thriller but "a truly profound work" with much to say about "the paradoxes and reversals of mother-child love."

A caveat: The uniqueness of Jack's voice all but disappears in the book's second half, said Deirdre Donahue in USA Today.

4. Parrot & Olivier in America

by Peter Carey

(Knopf, $27)

It takes a foreign-born writer to remind us that America is "one long picaresque novel," said Susan Salter Reynolds in the Los Angeles Times. Here, Australian native Peter Carey reaches back to Alexis de Tocqueville's time to create Olivier de Garmont, a fictional twist on America's greatest critic. Carey's version of the French political philosopher is a fussy aristocrat fascinated with American egalitarianism yet not bold enough to break free from the "prison of his class." Eventually, Garmont does go native, said Yvonne Zipp in The Christian Science Monitor. "That night I dined as the Americans dined, that is, I had a vast amount of ham," begins one of his hilarious reports. Garmont’s exchanges with Parrot, his servant and foil, produce a novel pregnant with insights about Carey's adopted country — "enough to snag your imagination on," and then some.

A caveat: Carey's novel "lacks the dark shadows that make the best comedies truly memorable," said Hephzibah Anderson in Bloomberg.

5. Super Sad True Love Story

by Gary Shteyngart

(Random House, $26)

Gary Shteyngart's latest novel easily lives up to its title, said Terrence Rafferty in Slate. A "spectacularly clever dystopian satire" set in a future that might as well be next Tuesday, Shteyngart's "super sad" story unfolds mostly through the diaries of Lenny, a schlubby salesman who peddles eternal-life therapy to rich people. In the opening pages, Lenny declares undying love for Eunice Park, a Fort Lee, N.J., native 15 years his junior who for the moment "is just needy enough to respond to Lenny's ardor." But Shteyngart reserves his most poignant satire for the novel's "second love story," said Michael Schaub in NPR. The author's "obvious affection for America" is the source of the story's deeper sadness, as Lenny and Eunice contend with a U.S. that's become "a financially strapped police state." At its best, the novel is a humorous and chilling "cri de coeur" from an author frightened about his country's fate.

A caveat: In its worst pages, said Alexander Theroux in The Wall Street Journal, the book resembles a "black-comedy version of 1984 but without a philosophical core."

How the books were chosen: Rankings are based on end-of-year recommendations published by The Atlantic, The Christian Science Monitor, the Cleveland Plain-Dealer, The Economist, the Los Angeles Times, the Minneapolis Star Tribune, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Publishers Weekly, Salon, the San Francisco Chronicle, Slate, Time, and The Washington Post.