E-books: A library in your pocket

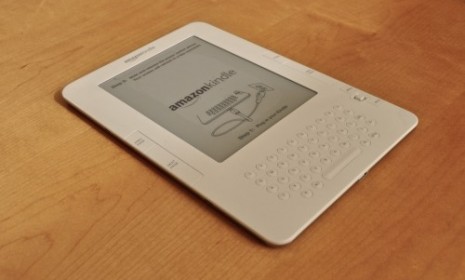

Will ‘e-readers’ like Amazon’s Kindle and Sony’s Reader replace books?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How many people read e-books?

Electronic books currently account for just 2 percent of the $35 billion-a-year book market, but sales are doubling each month even as the overall book market has been declining. Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon, which makes the Kindle, galvanized the publishing industry in May after he announced that when Amazon customers have a choice between digital and physical versions of a title, they opt for the digital version 35 percent of the time. That’s especially impressive given that there are only about 1 million Kindles in use worldwide. The debut in August of Sony’s Reader, whose basic model sells for $199, while Amazon’s goes for $299, should spur even more sales of digital books. With both devices an entire book can be downloaded in a minute or less, and hundreds of books can be stored in a slim tablet that fits in a purse or backpack. E-readers, says Web publisher Rob Grimshaw, “potentially could revolutionize the consumption of content in much the same way the Internet did.”

What do book publishers think of e-readers?

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

They’re deeply ambivalent. They don’t like sharing the sales price of books with Amazon and other e-book makers, but they certainly are cheered that owners of e-readers buy more books once they have such a device. “My book-buying habits changed when I got my Kindle,” says Don Leeper, president of a Minnesota company that digitizes print books. “I found I was buying many fewer printed books, but more books overall.” Publishers also say e-readers have great marketing and promotional value—many publishers now give away some books in electronic form, as a way of building a following for an author. When Random House earlier this year decided to charge nothing for readers to download the first volume of Naomi Novik’s Temeraire series of fantasy novels, sales of subsequent titles in the series jumped tenfold.

And newspaper publishers?

They’re also of two minds. With advertising in a deep slump and paying customers fleeing for free content on the Internet, newspapers and magazines are desperate to recapture subscribers and advertisers. Both Amazon and Sony offer newspapers and magazines for download to their e-readers, and programmers are developing ways to display ads. The dire financial predicament of the print industry, says Financial Times CEO John Ridding, “has created an urgency that has rightly focused attention on these devices.”

Why don’t publishers love them?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

They don’t want Amazon to control their pricing, their customers, and their business. Newspaper publishers chafe at the fact that Amazon sets subscription prices—which usually top out at $14.99 a month for newspapers and $7.99 for magazines—and takes as much as 70 percent of the proceeds. Book publishers complain that Amazon charges too little for popular titles and takes too big a cut, thereby reducing their profits. For example, Amazon charges about $16 for a hardcover copy of The Lost Symbol, the new novel by The Da Vinci Code author Dan Brown, but charges only $9.99 for the e-book version. Publishers also gripe that while Amazon knows which customers are buying which e-books, the publishers don’t, so they can’t pitch readers other titles. “Publishers are desperately hoping that they’ll be able to push their stuff through someone other than Jeff Bezos,” says technology writer Peter Kafka. They may soon get their wish. Gannett, publisher of USA Today, and Financial Times publisher Pearson are supporting Plastic Logic, a startup that’s developing a flexible electronic reading tablet that can display ads. And Apple is rumored to be developing its own reading device.

Do authors like e-books?

Authors tend to favor anything that helps them sell more books. Technology writer Josh Bernoff says that when the large-screen version of the Kindle became available last March at $489, there was a spike in sales of his latest book, Groundswell. “I make a lot less money for each Kindle unit sold,” he says, “but when my next book comes out, I bet that Kindle will be a big part of igniting the sales.” Authors also like e-books because they typically get a 25 percent royalty, compared with 10 percent to 15 percent for print. That’s because e-books eliminate the cost of paper and printing.

Could e-books make print obsolete?

A debate is raging on that question. Slate.com editor Jacob Weisberg argues that his Kindle 2 offers “a fundamentally better experience” than old-fashioned printed paper, and he predicts that “printed books, the most important artifacts of human civilization, are going to join newspapers and magazines on the road to obsolescence.” One small step in that direction occurred recently when Cushing Academy, a Massachusetts prep school, announced that it would give away its entire 20,000-book library and convert the space into an electronic “learning center,” complete with 18 e-readers. The news sent a shudder through the spines of book lovers everywhere. “I’m going to miss the books,” says Cushing librarian Liz Vezina. “The smell, the feel, the physicality of a book is something really special. There’s something lost when they’re virtual.”

A question of ownership

The irony was almost too perfect. Last summer, Amazon discovered that some of its customers had bought an electronic version of George Orwell’s 1984 published by a company that didn’t own the copyright. Amazon’s solution was to reach electronically into its customers’ Kindles and delete the book. Many customers said that it was as if the novel’s “Big Brother” had come to life. But the incident revealed something that many Kindle owners hadn’t fully understood before: They don’t own their Amazon e-books; they rent them. What customers are buying is a license granted by Amazon to read copyrighted material. And Amazon can revoke that license pretty much whenever it wants. Although Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos apologized to customers and promised to “make better decisions” in the future, Amazon’s terms of service haven’t changed. The company still claims the right to delete books from customers’ Kindles whenever it sees fit.