The prison nation

The U.S. has more people behind bars than any other nation, and its prisons are now bursting at the seams. Why?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How many Americans are in prison?

The numbers are startling. Some 2.3 million Americans are in prison, while another 5.1 million are on probation or parole. Altogether, the 7.4 million people in the criminal-justice system outnumber the individual populations of 38 states. Prior to the 1970s, the U.S. incarceration rate was similar to that of other nations. But the U.S. inmate population has nearly tripled in the past quarter-century, making the U.S. incarceration rate the highest in the world—almost five times the world average, surpassing even China and Russia. With only 5 percent of the world’s population, the U.S. has 25 percent of the world’s prisoners in its jails. “The current American prison system,” said

Brown University’s Glenn Loury, “is a leviathan unmatched in human history.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why are so many people in jail?

Rising crime rates in the 1960s led to decades of tough-on-crime politics, with legislators passing mandatory minimum sentences, “three-strikes” laws that impose lengthy sentences on three-time offenders, and “zero-tolerance” drug laws. (Nationally, one-quarter of inmates are serving time for drug offenses.) Politicians at all levels remain extremely reluctant to take anything but the hardest line on crime, and at the same time, seek to spend as little as possible on the prisons that warehouse all those inmates. California State Assembly Speaker Karen Bass has tried, without success, to convince her colleagues to reduce the number of low-level offenders behind bars in order to focus the state’s shrinking resources on hardened criminals. But she is an exception, with most politicians backing the lock-’em-up-and-throw-away-the-key philosophy. “You have an absolute hysteria,” Bass says.

Has tougher sentencing reduced crime?

Yes. Crime has declined significantly across the nation since peaking in the early 1990s. “One of the reasons crime rates

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

are so low,” says the Heritage Foundation’s Brian Walsh, “is because we changed our federal and state systems to make sure that people who commit crimes, especially violent crimes, actually have to serve significant sentences.” The simple reality is that when anti-social people are in jail, they can’t commit crimes. But reformers say that even if tough policies helped bring down the crime rate, such efforts long ago passed a point of diminishing returns. New York saw its violent-crime rate drop 40 percent between 1997 and 2007. At the same time, the state’s incarceration rate dropped 15 percent, proving that crime and the incarceration rate could drop in tandem. But most states kept sending more and more people to jail throughout the past decade—without considering the consequences.

What was the result?

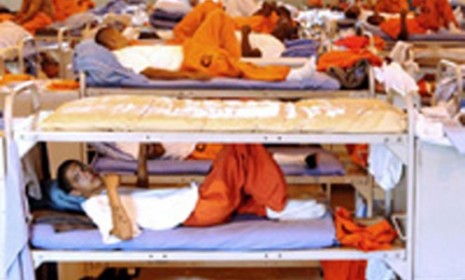

Overcrowded prisons, strained budgets, and the growing likelihood that prisons will become powder kegs. California is ground zero for these troubling trends. After a decade of court orders demanding improvements in jail conditions, the state’s prison system still houses twice as many inmates as it was built to hold. Inmates double up in small cells designed as singles or sleep on cots in corridors and public rooms. Racial tensions, gang activity, and prison violence, including rape, are rampant. In August, 1,300 inmates at the overcrowded state prison in Chino went on a rampage, leaving 175 injured and six dormitories wrecked. A federal court has ordered California to reduce its 170,000-inmate population by 40,000, even as the state has cut $1 billion from its $10.8 billion corrections budget. The system, says Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, is “collapsing under its own weight.”

What are the alternatives?

Reformers emphasize punishment that is swift, certain, and limited in duration—in contrast to drawn-out court appearances culminating in lengthy sentences. To curtail recidivism, they advocate stricter out-of-jail supervision, using a range of technologies—from GPS devices to rapid-result drug tests—to keep close tabs on parolees. “Today, two-thirds of those who leave prison will be back within three years,” says UCLA law professor Mark Kleiman. “The exit from a prison is a revolving door.” By monitoring parolees and probationers more aggressively, Kleiman argues, both the crime rate and the incarceration rate can be cut.

Is prison reform viable?

Perhaps, if state budget crises get bad enough. Criminal-justice systems from coast to coast are stretched to the limit. But despite the social and financial costs of the status quo—it costs roughly $29,000 to house a single inmate for a year—there is no political reward in advocating reform. With states crying for budget relief, Sen. Jim Webb, a Virginia Democrat, has seized the moment, introducing legislation that would create a national commission to study criminal-justice reform. “There are only two possibilities,” Webb said of the nation’s unparalleled incarceration rate. “Either we have the most evil people on earth living in the United States, or we are doing something dramatically wrong in terms of how we approach the issue of criminal justice.”

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie