Why all kids are liars

By their teenage years, all children are remarkably good at lying, says author Po Bronson. For this, parents have no one to blame but themselves.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

By their teenage years, all children are remarkably good at lying, says author Po Bronson. For this, parents have no one to blame but themselves.

In the last few years, a handful of intrepid scholars have decided it’s time to try to understand why kids lie. For a study to assess the extent of teenage dissembling, Dr. Nancy Darling, then at Penn State University, recruited a special research team of a dozen undergraduate students, all under the age of 21. Using gift certificates for free CDs as bait, Darling’s Mod Squad persuaded high school students to spend a few hours with them in the local pizzeria.

Each student was handed a deck of 36 cards, and each card in this deck listed a topic teens sometimes lie about to their parents. Over a slice and a Coke, the teen and two researchers worked through the deck, learning what things the kid was lying to his parents about, and why.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“They began the interviews saying that parents give you everything and,

yes, you should tell them everything,” Darling observes. By the end of the interview, the kids saw for the first time how much they were lying and how many of the family’s rules they had broken. Darling says 98 percent of the teens reported lying to their parents.

Out of the 36 topics, the average teen was lying to his parents about 12 of them. The teens lied about what they spent their allowances on, and whether they’d started dating, and what clothes they put on away from the house. They lied about what movie they went to, and whom they went with. They lied about alcohol and drug use, and they lied about whether they were hanging out with friends their parents disapproved of. They lied about how they spent their afternoons while their parents were at work. They lied about whether chaperones were in attendance at a party or whether they rode in cars driven by drunken teens.

Being an honors student didn’t change these numbers by much; nor did being an overscheduled kid. No kid, apparently, was too busy to break a few rules.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

For two decades, parents have rated “honesty” as the trait they most wanted in their children. Other traits, such as confidence or good judgment, don’t even come close. On paper, the kids are getting this message. In surveys, 98 percent said that trust and honesty were essential in a personal relationship. Depending on their ages, 96 percent to 98 percent said lying is morally wrong.

So when do the 98 percent who think lying is wrong become the 98 percent

who lie?

It starts very young. Indeed, bright kids—those who do better on other academic indicators—are able to start lying at 2 or 3. “Lying is related to intelligence,” explains Dr. Victoria Talwar, an assistant professor at Montreal’s McGill University and a leading expert on children’s lying behavior. A child who is going to lie, Talwar says, must recognize the truth, intellectually conceive of an alternate reality, and be able to convincingly sell that new reality to someone else.

By their fourth birthday, almost all kids will start experimenting with lying in order to avoid punishment. Because of that, they lie indiscriminately—whenever punishment seems to be a possibility. A 3-year-old will say, “I didn’t hit my sister,” even if a parent witnessed the child’s hitting her sibling.

Most parents hear their child lie and assume he’s too young to understand what lies are or that lying’s wrong. They presume their child will stop when he gets older. Talwar has found the opposite to be true—kids who grasp early the nuances between lies and truth use this knowledge to their advantage, making them more prone to lie when given the chance.

Many parenting websites and books advise parents to just let lies go—they’ll grow out of it. The truth, according to Talwar, is that kids grow into it. In studies where children are observed in their natural environment, a 4-year-old will lie once every two hours, while a 6-year-old will lie about once every hour and a half. Few kids are exceptions.

By the time a child reaches school age, the reasons for lying become more complex. Avoiding punishment is still a primary catalyst, but lying also becomes a way to increase a child’s power and sense of control—by manipulating friends with teasing, or by bragging to assert status.

In longitudinal studies, a majority of 6-year-olds who frequently lie have it socialized out of them by age 7. But if lying has become a successful strategy for handling difficult social situations, a child will stick with it. About half of all kids do—and if they’re still lying a lot at 7, then it seems likely to continue for the rest of childhood. They’re hooked.

One of Talwar’s experiments is known in the lab as “the Peeking Game.” Through a hidden camera, I watched a 6-year-old named Nick play it with another one of Talwar’s students, Cindy Arruda. Arruda told Nick they were going to play a guessing game. Nick was to sit facing the wall and try to guess the identity of a toy Arruda brought out, based on the sound it made. If he was right three times, he’d win a prize.

The first two were easy: a police car and a crying baby doll. But then Arruda brought out a toy soccer ball and placed it on top of a greeting card that played music. She cracked the card, triggering it to play a music-box jingle of Beethoven’s “Für Elise.” Nick, of course, was stumped.

Arruda suddenly said she had to leave the room for a bit, promising to be right back. She admonished Nick not to peek at the toy while she was gone. Nick struggled not to, but at 13 seconds, he gave in and looked.

In fact, 76 percent of kids Nick’s age take the chance to peek during the game, and when asked if they peeked, 95 percent lie about it.

Sometimes a researcher will read the child a short storybook before she asks about the peeking, either “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” or “George Washington and the Cherry Tree.” The latter ends with young George confessing to his father that he chopped down a prized tree. “Hearing you tell the truth instead of a lie,” his father says, “is better than if I had a thousand cherry trees.”

Now, which story do you think reduced lying more? Hearing about a boy who was eaten by a wolf because of his repeated lies did not cut down on lying in Talwar’s experiments. Indeed, after hearing the story, kids lied a little more than normal. Meanwhile, hearing the George Washington fable reduced lying a sizable 43 percent.

Apparently, the fact that lies get punished is not news to children. In studies, scholars find that kids who live in threat of consistent punishment don’t lie less. Instead, they become better liars—learning to get caught less often.

Ultimately, it’s not the threat of punishment that stops kids from lying—it’s the process of socialization. According to Talwar, parents need to teach kids the worth of honesty, as George Washington’s father did.

The most disturbing reason children lie is that parents teach them to.According to Talwar, they learn it from us. “We don’t explicitly tell them to lie, but they see us do it. They see us tell the telemarketer, ‘I’m just a guest here.’ They see us boast and lie to smooth social relationships.”

Consider how we expect a child to act when he opens a gift he doesn’t like. We instruct him to swallow all his honest reactions. We applaud if he comes up with a white lie. Encouraged to tell so many white lies, children gradually get comfortable with being disingenuous. They learn that honesty only creates conflict, and dishonesty is an easy way to avoid conflict. And while they don’t confuse white-lie situations with lying to cover their misdeeds, they bring this emotional groundwork from one circumstance to the other. It becomes easier, psychologically, to lie to a parent. So if the parent says, “Where did you get these Pokémon cards? I told you, you’re not allowed to waste your allowance on Pokémon cards!” this may feel to the child very much like a white-lie scenario—he can make his father feel better by telling him the cards were extras from a friend.

Now, compare this with the way children are taught not to tattle. Tattling has received some scientific interest, and researchers have spent hours observing kids at play. They’ve learned that for every time a child seeks a parent for help, there are 14 instances when he was wronged but did not run for aid. So when a frustrated child finally comes to a parent and is told not to tattle, he hears, in effect, “Stop bringing me your problems!”

By the middle years of elementary school, a tattler is also about the worst thing a kid can be called on the playground. And each year, the problems kids deal with grow exponentially. They watch other kids cut class, vandalize walls, and shoplift. Keeping their mouth shut is easy: They’ve been encouraged to do so since they were little, and to seek out a parent for help is, from a teen’s perspective, a tacit admission that he’s not mature enough to handle it alone. By withholding details about their lives, adolescents carve out both a social domain and an identity that are theirs alone.

The big surprise in the research is when this need for autonomy is strongest. It’s not mild at 12, moderate at 15, and most powerful at 18. Darling’s scholarship shows that the objection to parental authority peaks around ages 14 to 15. In fact, this resistance is slightly stronger at age 11 than at 18.

In her study of teenage students, Darling also mailed survey questionnaires to the parents of the teenagers interviewed, and it was interesting how the two sets of data reflected on each other. First, she was struck by parents’ vivid fear of pushing their teens into outright hostile rebellion. “Many parents today believe the best way to get teens to disclose is to be more permissive and not set rules,” Darling says.

Darling found, however, that permissive parents don’t actually learn more about their children’s lives. “Kids who go wild and get in trouble mostly have parents who don’t set rules or standards. The kids take the lack of rules as a sign their parents don’t care.”

Pushing a teen into rebellion by having too many rules was a sort of myth. “That actually doesn’t happen,” remarks Darling. She found that most rules-heavy parents don’t actually enforce them. “It’s too much work,” she says.

“Ironically, the type of parents who are actually most consistent in enforcing rules are the same parents who are most warm and have the most conversations with their kids,” Darling observes. They’ve set a few rules over certain key spheres of influence, and they’ve explained why the rules are there. Over life’s other spheres, they supported the child’s autonomy, allowing them freedom to make their own decisions.

Not surprisingly, the kids of these parents lied the least. But they did lie. Rather than hiding 12 out of 36 areas from their parents, they might be hiding as few as five.

From a story that appeared in New York Magazine. Additional reporting by Ashley Merryman. ©2008 by Po Bronson. Distributed by Tribune Media Services. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown Ltd.

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders

-

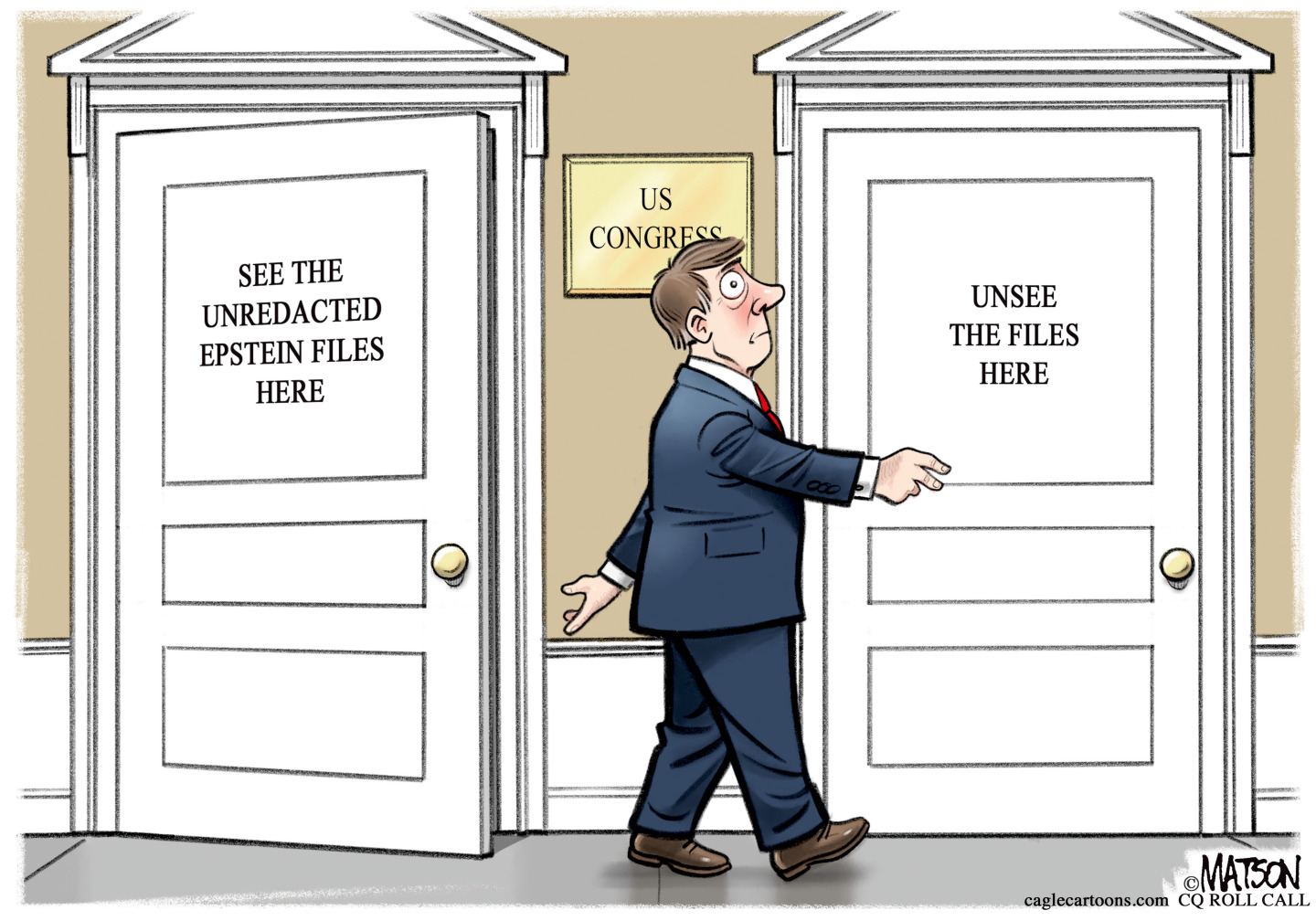

Political cartoons for February 11

Political cartoons for February 11Cartoons Wednesday's political cartoons include erasing Epstein, the national debt, and disease on demand

-

The Week contest: Lubricant larceny

The Week contest: Lubricant larcenyPuzzles and Quizzes