America's controversial path to the atomic bomb

The bombing of Hiroshima followed years of escalation by the U.S., but was it necessary?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This article originally appeared in History of War magazine issue 149.

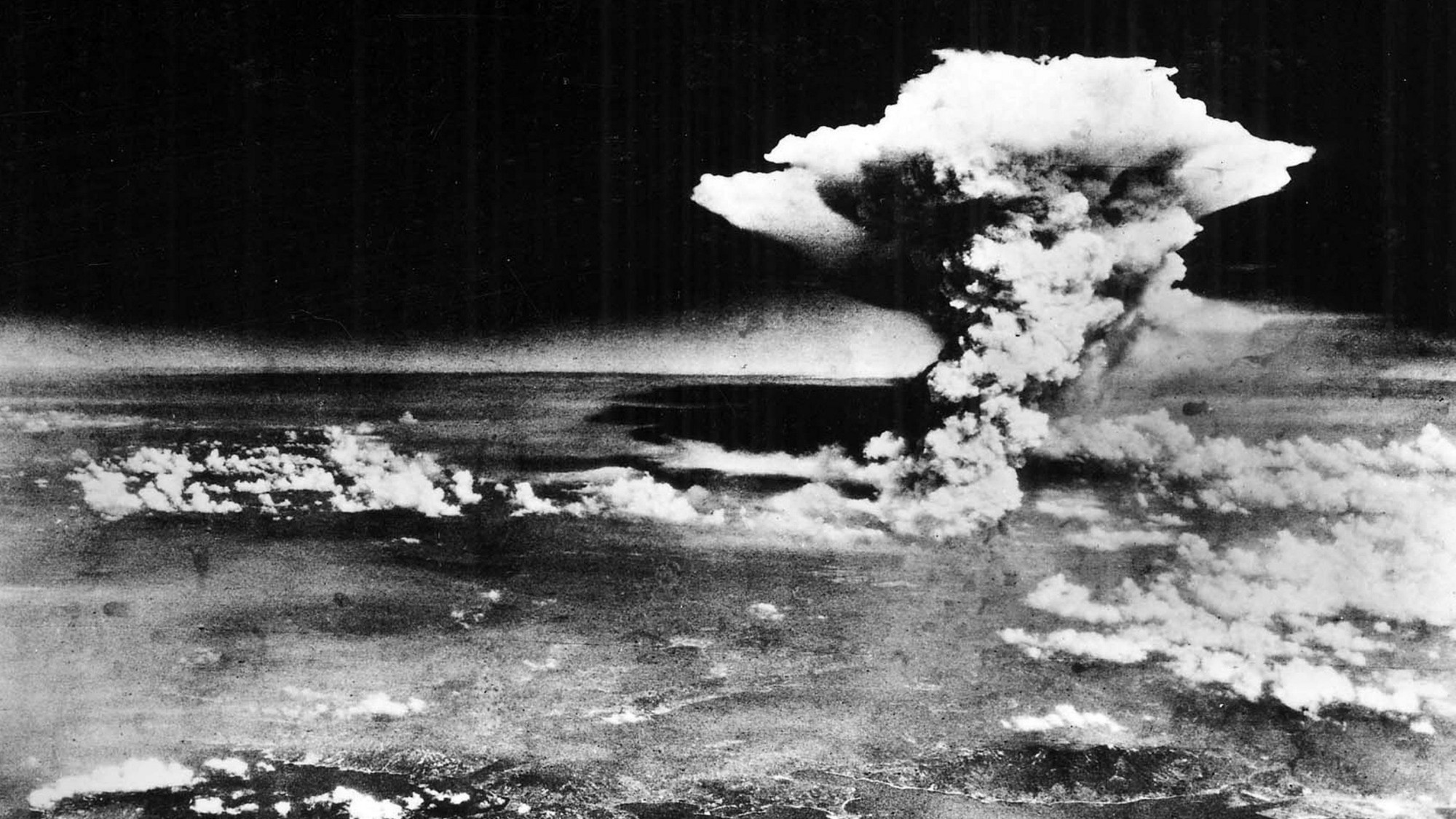

The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, shocked the world. It marked the dangerous new dawn of nuclear weapons, and foreshadowed the horrific potential of World War Three should it ever break out.

The atomic bomb was a catastrophic escalation that preceded the end of the Second World War; however it followed years of escalating conventional aerial bombardment of Japan by the Allies. "If they were prepared to firebomb the country to its knees, why wouldn't they drop an atomic bomb?" historian Iain MacGregor told History of War magazine.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

He adds that the firebombing of Japanese cities was the point of no return that made atomic bombing acceptable to the American leadership. "It was just another piece of ordnance."

An aerial photograph shows the ruined areas of Tokyo, destroyed in the March 9 bombing

During the Spanish Civil War, Hitler's Condor Legion devastated Guernica with high-explosive and incendiary bombs. Hamburg, Dresden, Cologne, Coventry and other European cities followed in the Second World War.

In the Pacific Theatre, hundreds of thousands died in Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe and more when incendiary bombs ignited wooden homes into unstoppable firestorms. The crescendo of this devastating strategy came when the atomic bombs Little Boy and Fat Man were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

At the outset of the Second World War President Franklin D. Roosevelt implored the belligerents to avoid civilian casualties when bombing. Yet even as he made this plea, one of the USA's greatest aviation achievements and the eventual bearer of weapons of mass destruction, the B-29 Superfortress, was already in development.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The B-29 strategic bomber

A line of B-29 Superfortress bombers under construction at the Boeing plant in Wichita, Kansas, October 1944

"The strategy would be that machines do the fighting to save a hell of a lot of casualties. That doctrine dominated American policy even before Pearl Harbor," says MacGregor, whose book The Hiroshima Men chronicles the stories of the key figures involved in the atomic bomb.

He also notes the economic significance of an aircraft programme that cost more than the Manhattan Project: "Investing that kind of money meant rejuvenating America's economy.

"The aircraft industry had taken a pounding during the Great Depression. They deliberately made sure to build the plane in middle America, partly for security — no saboteur could get near it — but also because it revived entire regions of the Midwest."

It was two-and-a-half years after the attack on Pearl Harbor that the U.S. unleashed the destructive capabilities the B-29, forced by the blood-soaked Asia-Pacific campaign. During the war, Japan's military culture was ruled by a "suicidal urge", as co-author of Victory '45 Al Murray puts it. This meant any advances towards the Home Islands had a staggering cost.

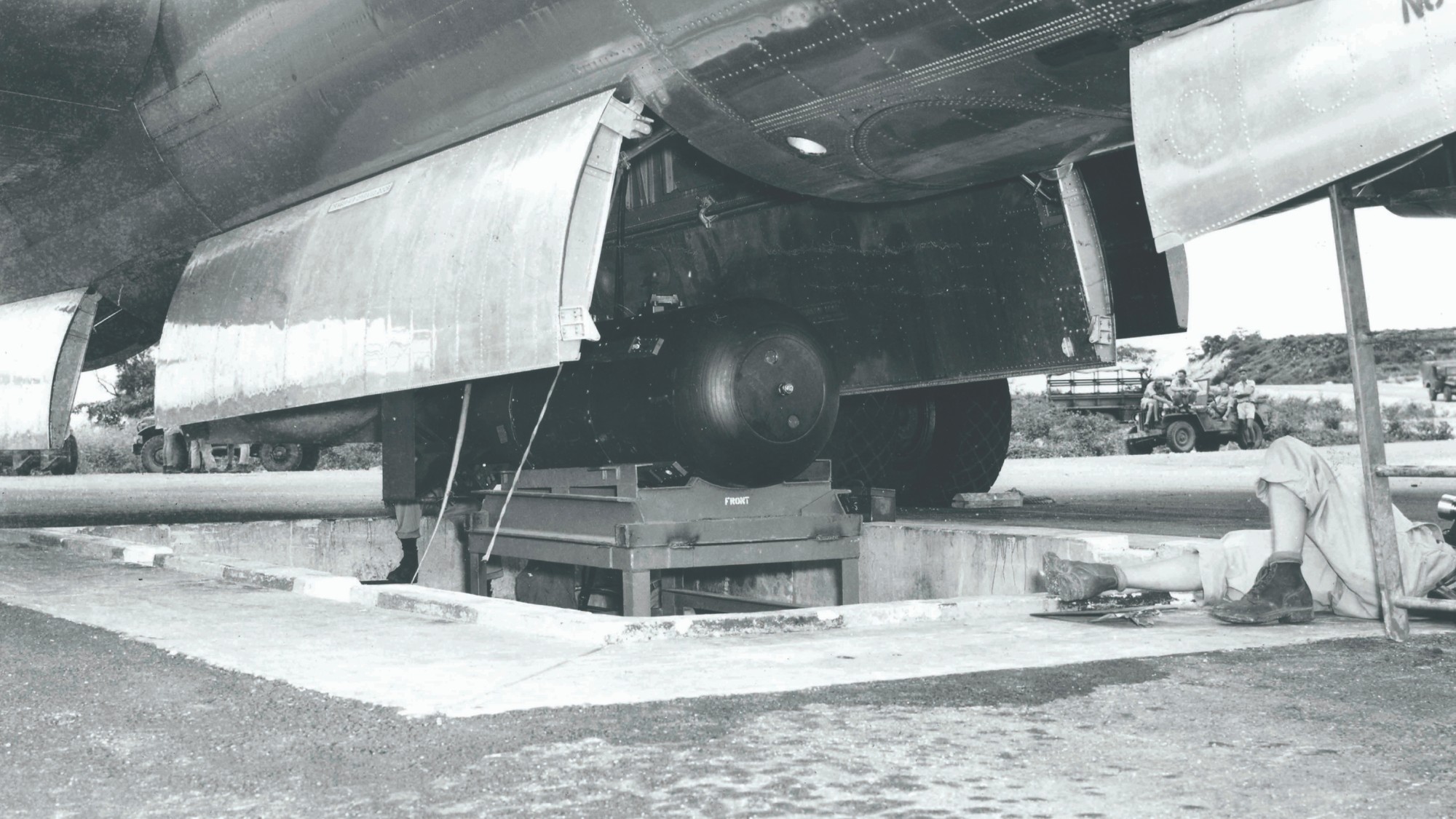

The 'Little Boy' atomic bomb is loaded into the B-29 Enola Gay

"The Japanese also believed that the American psyche wouldn't have the stomach for the brutal, attritional warfare needed to get to the Home Islands. The next three years proved them wrong," says MacGregor, noting that the U.S. took more casualties in the first six months of 1945 than in the previous three years combined.

U.S. commanders looked to the B-29 as the weapon that could crush Japanese resistance and minimise Allied casualties. The Americans had outfought Japanese expectations, but U.S. deaths in the Asia-Pacific, rapidly approaching their final total of over 100,000, were making people back home queasy.

"The next jump-off point was an amphibious assault on the Japanese mainland. Military reports suggested that in the first few months there could easily have been a million Allied and four million civilian casualties," says MacGregor. In New Mexico, the world's greatest physicists were secretly working on a weapon of mass destruction that could avoid America's bloodiest campaign yet.

The firebombing of Tokyo

In August 1944 General Curtis LeMay took charge of XX Bomber Command, responsible for the bombing campaign against Japan. He found that the powerful jet stream winds over the Home Islands made high-altitude precision bombing almost impossible. So instead of relying on accuracy, he harnessed the destructive potential of tonnes of incendiary bombs.

This was most terribly demonstrated during Operation Meetinghouse, a large raid on the capital Tokyo on the night of March 9-10, 1945. This bombing raid destroyed vast swathes of the capital and killed over 100,000 people, mainly civilians, more than four-times the estimated deaths during the bombing of Dresden a month earlier.

Meetinghouse was a new and terrible milestone in the destructive capability of air power, leaving more than an ambiguous question mark over the legality and morality of the tactic. "If we lose, we'll be tried as war criminals," LeMay soberly remarked.

Civilians gather in a ruined area of Tokyo after the March 9 bombing

Over the following five months, B-29 raids turned 66 Japanese cities to ash. Traditional wood and paper housing erupted into flames across the country. Estimates of the deaths from the bombing campaigns against Japan in the United States Strategic Bombing Survey reports range from 333,000 to 900,000, including Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

LeMay's use of napalm was horrifically effective, with 56-84 percent of the fatalities caused by burns. Despite the destruction, firebombing proved a failure in forcing the Japanese government to surrender. Unimaginable casualties, and the evacuation of a quarter of Japan's urban population, could not end support for the war effort.

"The Japanese were controlling information so tightly that the population didn't even know they were losing," Al Murray told History of War. "[But] perhaps there was a sneaking suspicion in the backs of their minds that the war wasn't going as well as it could." The Allies needed a more destructive weapon to break the Japanese government's ironclad commitment to fight to the bitter end.

This article originally appeared in History of War magazine issue 149. Click here to subscribe to the magazine and save on the cover price!

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

Why Greenland has been a US military stronghold since the Second World War

Why Greenland has been a US military stronghold since the Second World WarIn Depth American interest in acquiring Greenland is rooted in decades of military and economic strategy

-

Has Putin launched the second nuclear arms race?

Has Putin launched the second nuclear arms race?In Depth Historian Serhii Plokhy explains why the Kremlin’s nuclear proliferation has begun a dangerous new era of mutually assured destruction

-

How China rewrote the history of its WWII victory

How China rewrote the history of its WWII victoryIn Depth Though the nationalist government led China to victory in 1945, this is largely overlooked in modern Chinese commemorations

-

Thailand-Cambodia border conflict: colonial roots of the war

Thailand-Cambodia border conflict: colonial roots of the warIn Depth The 2025 clashes originate in over a century of regional turmoil and colonial inheritance

-

Mutually Assured Destruction: Cold War origins of nuclear Armageddon

Mutually Assured Destruction: Cold War origins of nuclear ArmageddonIn Depth After the US and Soviet Union became capable of Mutually Assured Destruction, safeguards were put in place to prevent World War Three

-

Argentina lifts veil on its past as a refuge for Nazis

Argentina lifts veil on its past as a refuge for NazisUnder the Radar President Javier Milei publishes documents detailing country's role as post-WW2 'haven' for Nazis, including Josef Mengele and Adolf Eichmann

-

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.

-

D-Day: how allies prepared military build-up of astonishing dimensions

D-Day: how allies prepared military build-up of astonishing dimensionsThe Explainer Eighty years ago, the Allies carried out the D-Day landings – a crucial turning point in the Second World War