The battle of Bamber Bridge

The new Railway Children film draws on a forgotten wartime episode: a skirmish between black and white US soldiers in Lancashire

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How does it feature in the film?

The Railway Children Returns features an African-American serviceman who is on the run in rural England from the military police, a story inspired by real events.

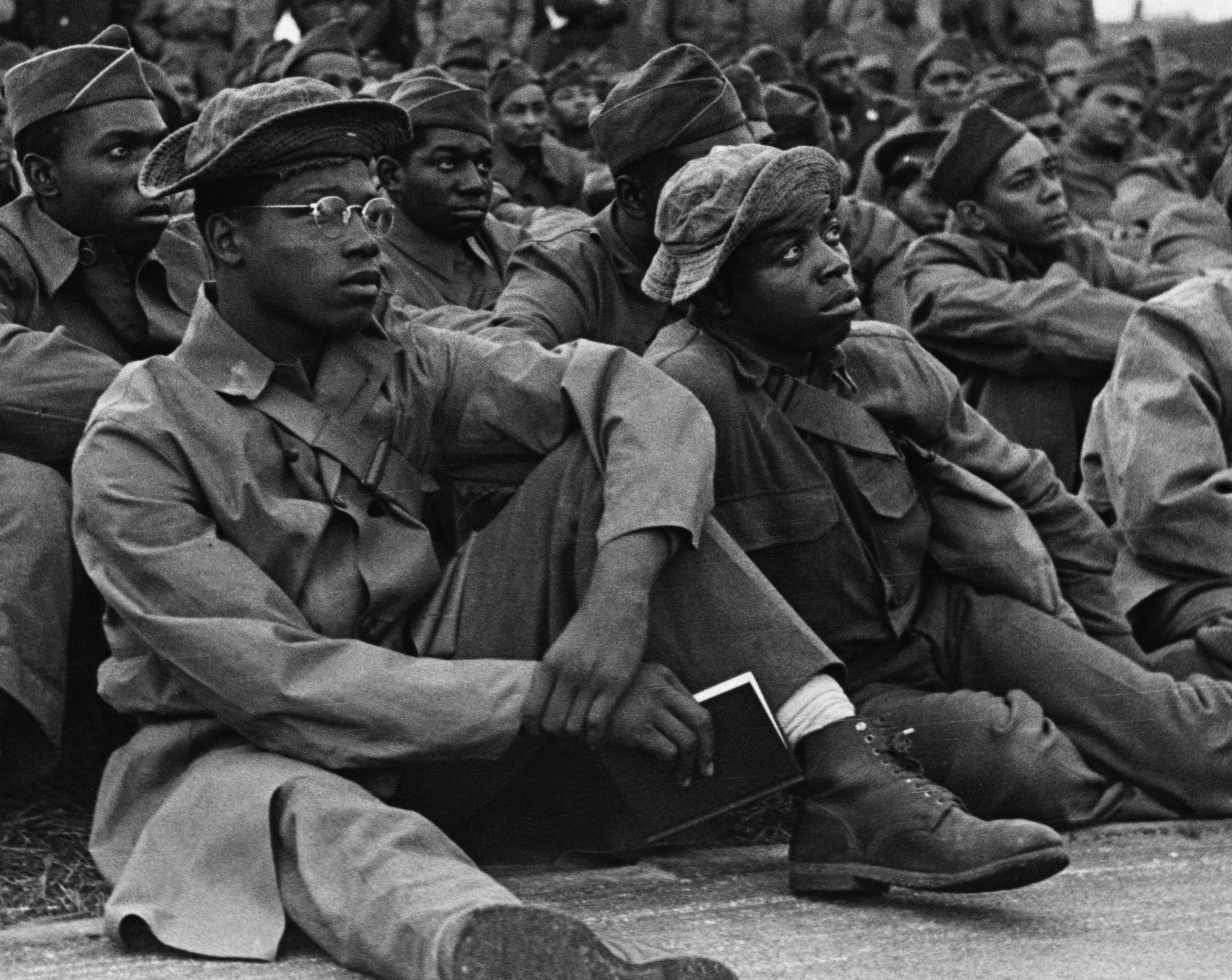

Between January 1942 and December 1945, some 1.5 million US servicemen came to Britain as part of the war effort. Their arrival was heralded as a “friendly invasion”, but there were some points of tension between the new arrivals and their hosts. One was the treatment of African-Americans. Around 150,000 black troops came to Britain. US society was still effectively segregated and, until late 1944, black soldiers were restricted to service and supply roles, rather than combat ones. In theory, in the US armed forces, as in society, they were “separate but equal”; in practice they were put into all-black units and treated as third-class citizens.

How did African-American servicemen fare in Britain?

They found themselves in a very different world to the US. Although they certainly encountered prejudice, Britain of course had no segregation, and they were generally welcomed as allies in the fight against fascism. Roi Ottley, writing in the Chicago magazine Negro Digest in 1942, said that “amicable and smooth relations” had soon developed between “the Negro troops and their British hosts”. The British, he said, were “inclined to accept a man for his personal worth”. He quotes a soldier saying: “I’m treated so a man don’t know he’s coloured until he looks in the mirror.” George Orwell remarked that American GIs were widely resented for being, in the famous phrase, “oversexed, overpaid and over here”, and that “the general consensus of opinion is that the only American soldiers with decent manners are Negroes”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why did their presence lead to tension?

Because the freedoms enjoyed by African-Americans conflicted with the de facto segregation of US forces, and the attitudes of the white majority, particularly Southerners. The fact that white women mixed with and dated black men – taboo in the US – infuriated some servicemen. Captain Vernon Gayle Alexander, a pilot from Kentucky, complained: “The blacks were dating the white girls and consequently if you went on a date [with] a white girl you don’t know if she’d been out with a coloured boy the night before or whether she hadn’t.” In some cases, US military police (MPs) tried to enforce segregation, by restricting entry to local pubs, or designating social nights as white or “coloured”. To quote Roi Ottley, Dixie – the South, with its “Jim Crow” segregation laws – “invaded” Britain. There were many clashes between white and black troops.

What sort of clashes?

Usually over women, or between MPs trying to enforce discriminatory rules and African-American soldiers – with the latter sometimes supported by British bystanders. According to Professor Alan Rice of the University of Central Lancashire, there were 44 such clashes between November 1943 and February 1944 alone. In some cases, such as in Bristol in July 1944, these escalated into riots. The most dramatic episode took place in Bamber Bridge, a village just outside Preston in Lancashire, where the US Eighth Army Quartermaster Truck Company, a black logistics regiment, was based from 1943.

What happened in Bamber Bridge?

US MPs called for a “colour ban” in Bamber Bridge’s three pubs. Landlords reacted defiantly by putting up signs that read: “Black Troops Only”. At one of these pubs, Ye Olde Hob Inn, on 23 June 1943 – only days after a major race riot in Detroit (see box) – there was a confrontation between MPs and black soldiers. The fight had started because of a heavy-handed intervention by two MPs, who sought to arrest Private Eugene Nunn for not wearing the proper uniform. A British soldier intervened, saying, “Why do you want to arrest them? They’re not doing anything or bothering anybody.” A fist fight ensued; the MPs left but returned with reinforcements.

How did the battle play out?

The facts were contested, but it seems the MPs started beating soldiers who were then walking with white women from the Auxiliary Territorial Service. Private Nunn punched an MP, and a violent melee broke out. An MP fired his handgun, hitting a black soldier, Private Lynn Adams, in the neck. Many Truck Company personnel, believing that they were under deadly assault, then raided their armoury, and warned residents to stay indoors. By midnight, several Jeep loads of MPs had arrived, with an armoured car fitted with a machine gun. A series of gunfights took place across the town (bullet holes were found in the NatWest bank during renovations in the 1980s). By 4am, it was over. One black solider, Private William Crossland, had died – “shot down in cold blood on a British street”, says Professor Rice. Seven others, including both MPs and African-Americans, were wounded.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What happened in the aftermath?

There were two separate courts martial. Four of those in the initial brawl were charged and found guilty. Three were sentenced to three to four years’ hard labour and dishonourable discharges; the fourth to two-and-a-half years’ hard labour. At the second trial, 32 soldiers were found guilty of crimes including mutiny, seizing arms, and firing upon officers. However, the sentences were later reduced, and reforms were made as a result: General Ira Eaker, commanding officer of the US army air forces, noted that these conflicts were often “the fault of the whites”; mixed black and white MP patrols were introduced. In 1948, US president Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, banning segregation in the armed forces. The incident itself was hushed up at the time, with only one short local newspaper report – but it was always remembered in the area as The Battle of Bamber Bridge.

-

Political cartoons for February 21

Political cartoons for February 21Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include consequences, secrets, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

American empire: a history of US imperial expansion

American empire: a history of US imperial expansionDonald Trump’s 21st century take on the Monroe Doctrine harks back to an earlier era of US interference in Latin America

-

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa Parks

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa ParksIn The Spotlight Inspired by the example of 19th century abolitionists, 15-year-old Colvin refused to give up her seat on an Alabama bus

-

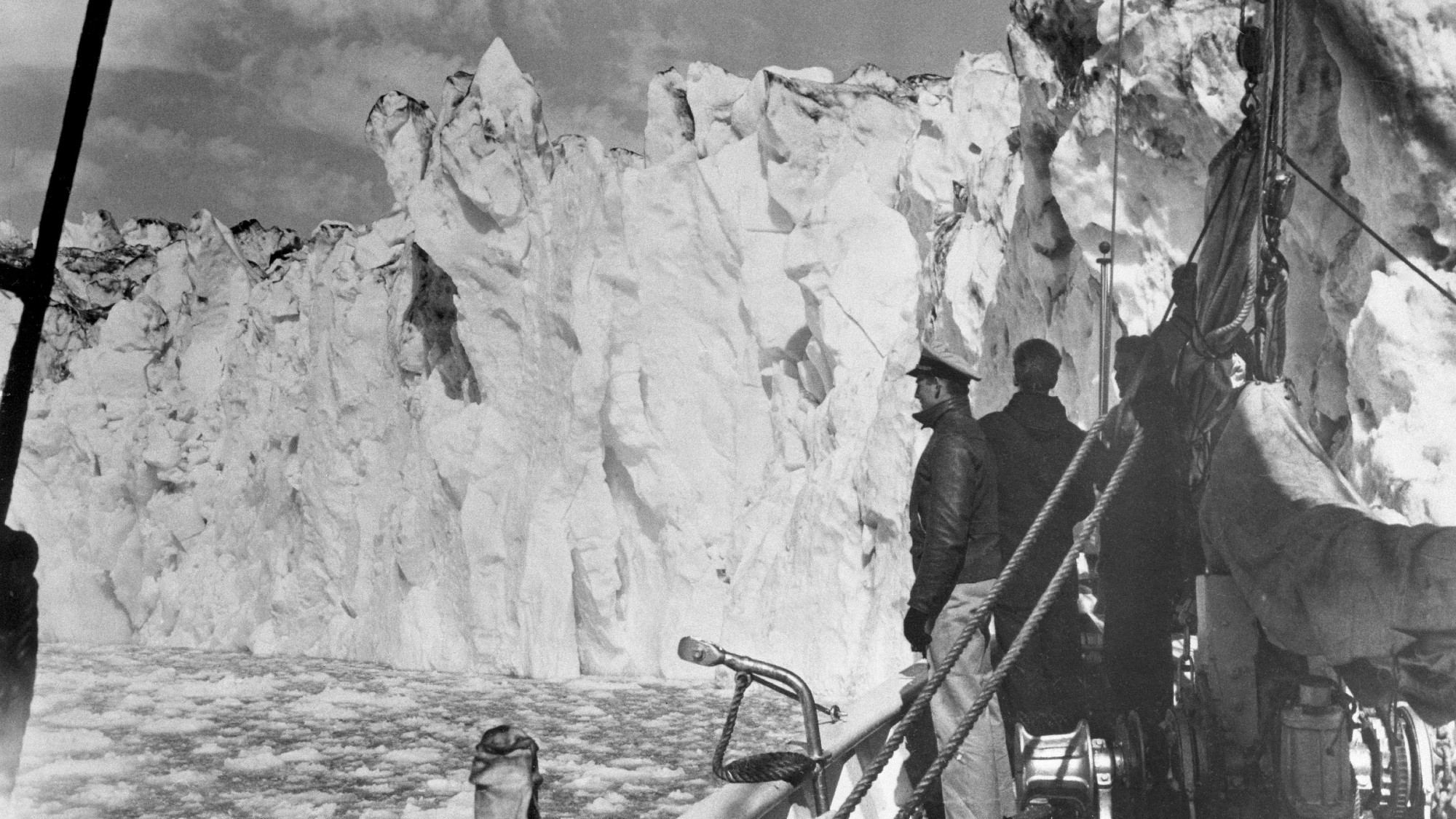

Why Greenland has been a US military stronghold since the Second World War

Why Greenland has been a US military stronghold since the Second World WarIn Depth American interest in acquiring Greenland is rooted in decades of military and economic strategy

-

Decking the halls

Decking the hallsFeature Americans’ love of holiday decorations has turned Christmas from a humble affair to a sparkly spectacle.

-

Hitler: what can we learn from his DNA?

Hitler: what can we learn from his DNA?Talking Point Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator is the latest documentary to posthumously diagnose the dictator

-

How China rewrote the history of its WWII victory

How China rewrote the history of its WWII victoryIn Depth Though the nationalist government led China to victory in 1945, this is largely overlooked in modern Chinese commemorations

-

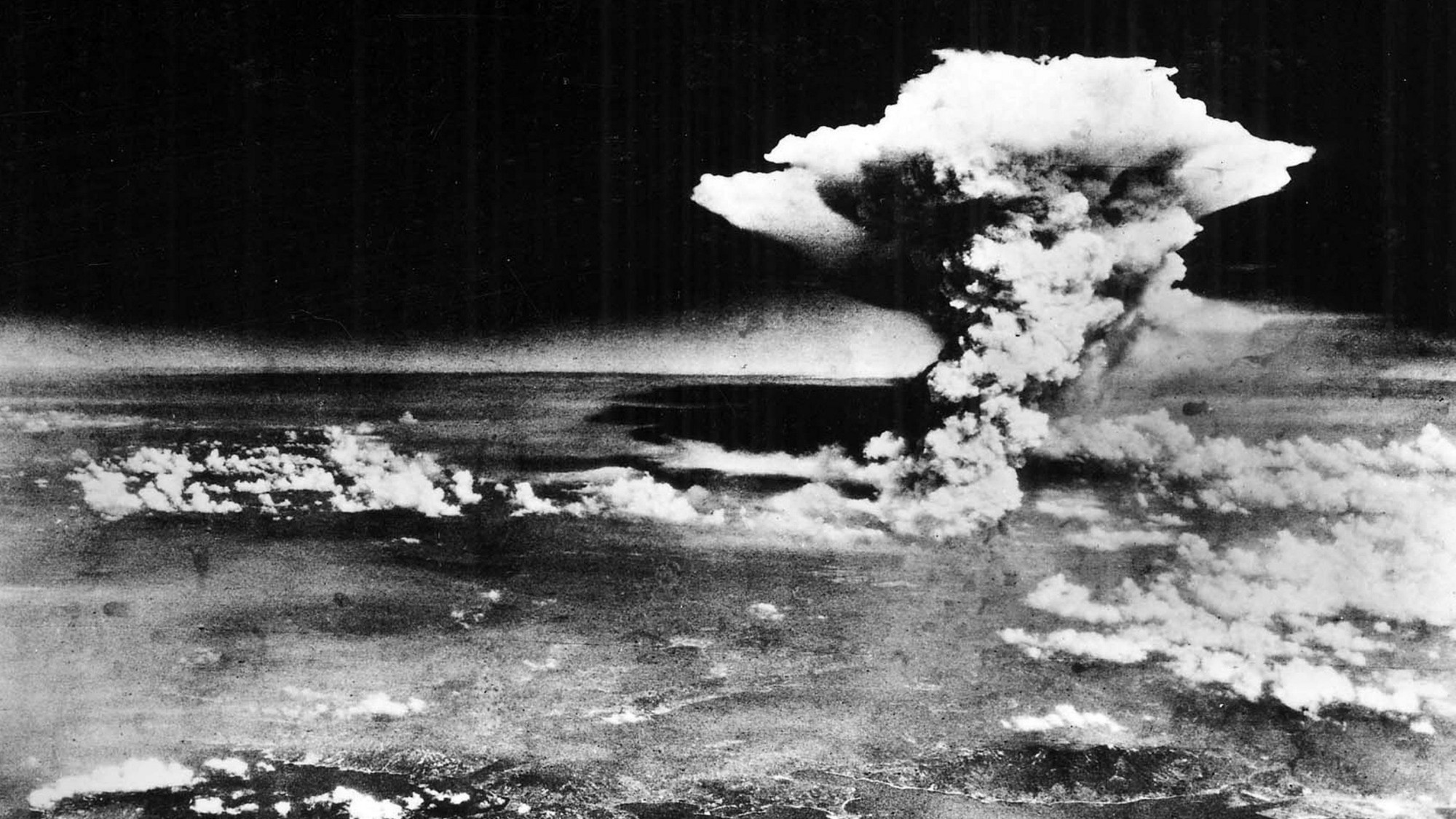

America's controversial path to the atomic bomb

America's controversial path to the atomic bombIn Depth The bombing of Hiroshima followed years of escalation by the U.S., but was it necessary?

-

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025The Explainer From prehistoric sunscreen to a brain that turned to glass, we've learned some surprising new facts about human history