The assassination of Malcolm X

The civil rights leader gave furious clarity to black anger in the 1960s, but like several of his contemporaries met with a violent end

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

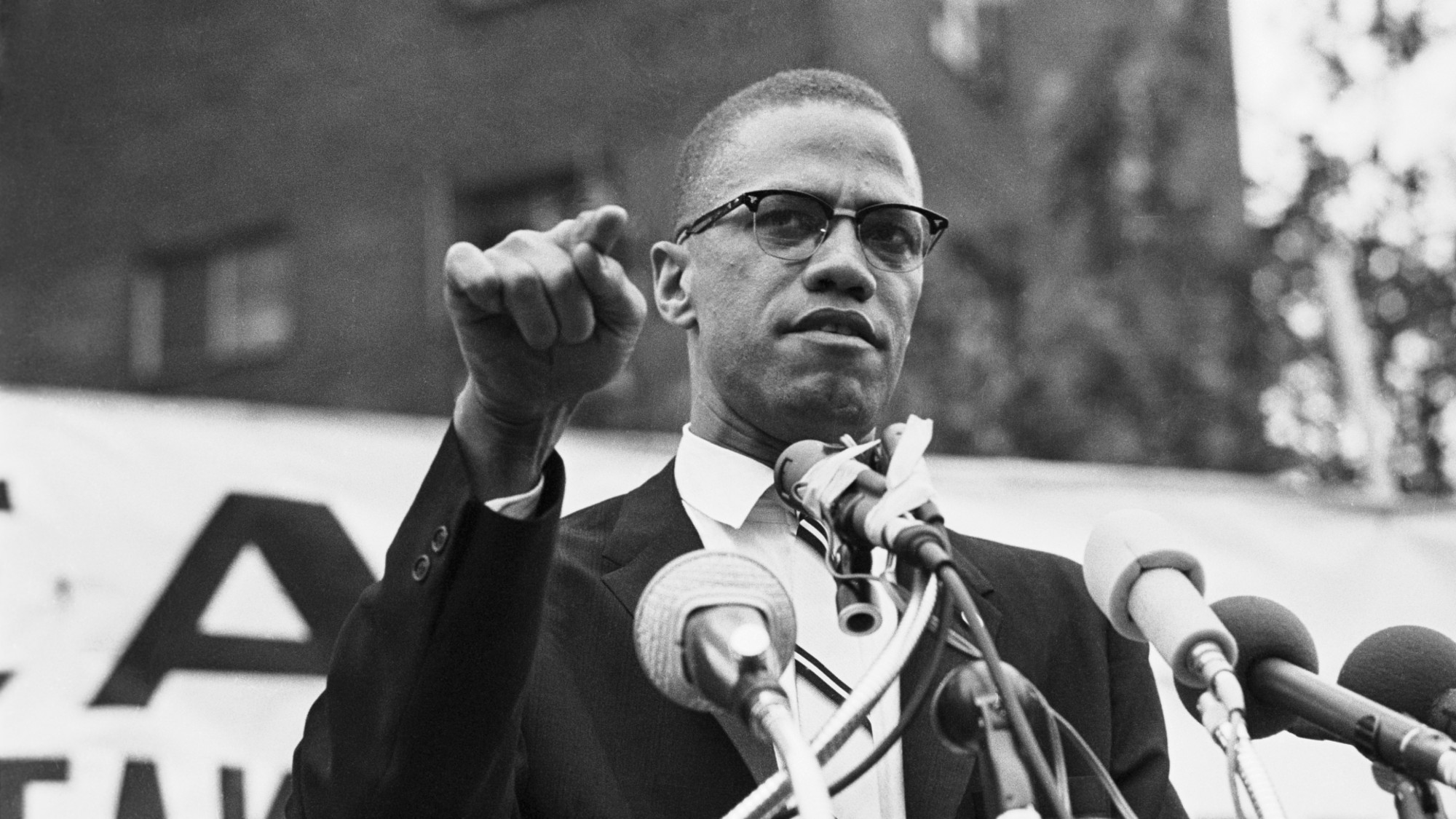

In the era of the civil rights movement, Malcolm X was America's most famous proponent of Black nationalism. A Muslim convert and a member of the Nation of Islam movement, Malcolm X believed that, rather than trying to integrate with the white majority, African Americans should seek economic and political independence. His powerful oratory skill gave voice to black pride – and, with furious clarity, to black anger.

What was Malcolm X's background?

Born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1925, he was one of seven children; his father, Earl, was a Baptist preacher and activist who died when Malcolm was six. At that time, they lived in Lansing, Michigan; his father was seen as a troublemaker by the Black Legion, a Ku Klux Klan splinter group. Malcolm's family home was burned down, and African Americans in Lansing believed his father had been murdered by a Black Legion mob – that they had killed him and staged the streetcar accident officially blamed for his death.

In 1939, Malcolm's mother, Louise, had a nervous breakdown, and he spent the rest of his childhood in foster care. Dropping out of school at 16, he took up various jobs – shining shoes, working on the railways – before ending up in Harlem, where he turned to crime: drug dealing, armed robbery, pimping. In 1946, he was jailed for burglary and served six-and-a-half years.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why did he join the Nation of Islam?

In 1948, at Norfolk Prison Colony in Massachusetts, he embraced the Nation of Islam on the advice of his brothers (later changing his name to Malcolm X – where X represented his unknown African name, replacing his "slave name"). The Nation is a sect based on Islam, black nationalism and black pride, with an eccentric mythology.

On his release in 1952, Malcolm X travelled across the US spreading its message. He'd read voraciously in prison, and proved to be a charismatic preacher and a gifted organiser. Elijah Muhammad, the Nation's leader, named him national representative, second only to himself. Thanks in no small part to Malcolm X, the sect grew from a few hundred members to about 500,000. He became a national figure – and a hate figure for much of white America. But in 1964, he left the Nation.

Why did he leave?

For some years, he'd been growing increasingly disillusioned. He had a strong puritanical streak and began to disapprove of Elijah Muhammad's theology and strategy, and the fact that Muhammad had fathered children with young Nation secretaries. And in 1963, he was suspended from his duties in the sect for 90 days, following the media storm that resulted from his description of John F. Kennedy's assassination as the "chickens coming home to roost".

After leaving, he made a pilgrimage to Mecca, and embraced Sunni Islam, adopting the name el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz. He then publicly disavowed the Nation's "racist philosophy", alluded to its links to the KKK (which shared the Nation's desire for a separate black ethno-state in the US South), and denounced Elijah Muhammad as a "religious faker". The Nation viewed this as a betrayal; in late 1964, the order was given to do him "terminal bodily harm".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How did he die?

At 2pm on 21 February 1965, Malcolm X arrived at the Audubon Ballroom in Washington Heights, where he was due to launch his new Organisation of Afro-American Unity: a black nationalist group that would welcome all African Americans, and lead mainstream civil rights initiatives: voter registration, rent strikes, campaigns for better housing. By then, Nation assassins had already made attempts on his life (a week earlier his house in Queens had been firebombed); but Malcolm X asked his security not to perform checks at the entrance, so as not to put off potential members.

As he began to speak in front of an audience including his wife, Betty, a smoke bomb was detonated from the back of the audience, prompting him to step from behind his podium to restore order. As he did so, a man from the fourth row charged towards him and shot him with a sawn-off shotgun. Two other men then ran to the stage and fired as well; Malcolm X was pronounced dead shortly after arriving at hospital. He was 39.

Who killed him?

Most historians believe that Malcolm X's killers were three men from the Nation's Newark mosque: Thomas Hagan, William Bradley and Leon Davis. Hagan was arrested at the scene, having been wounded by Malcolm X's security. However, two other Nation members, Muhammad A. Aziz and Khalil Islam, were convicted with Hagan in March 1966. Some 55 years later, in 2021, Aziz and Islam were finally exonerated; an investigation found that the FBI and the NYPD had withheld crucial evidence.

How is Malcolm X seen today?

Within the African-American community he is widely celebrated: at his funeral, his friend Ossie Davis called him "a prince – our own black shining prince!". His memoir, "The Autobiography of Malcolm X", written with Alex Haley and published eight months after his death, is seen as an American classic. But he is also widely reviled – inside and outside the black community – as an extremist demagogue.

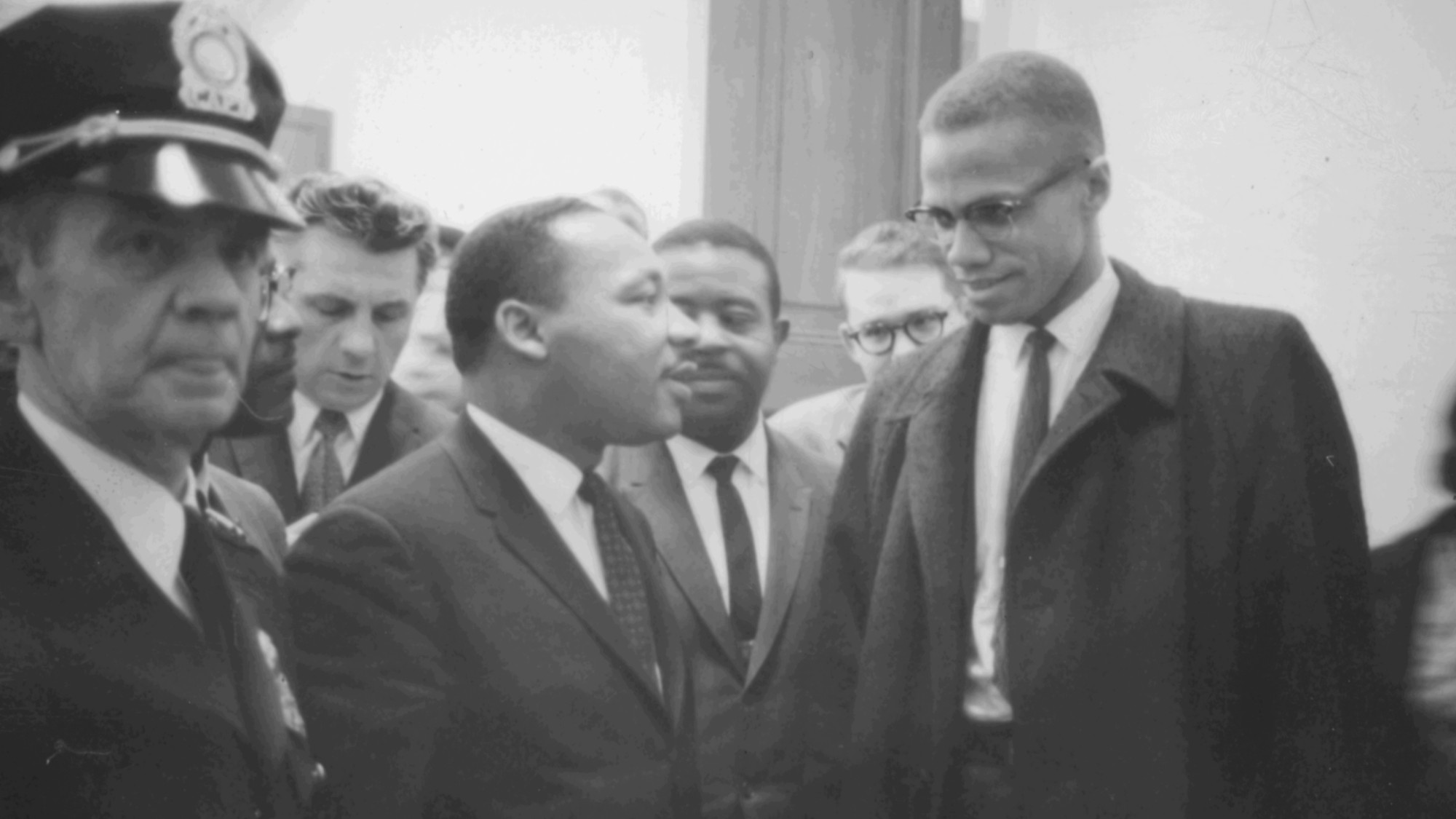

He was in some respects the polar opposite of his contemporary Martin Luther King Jr. King believed that America was perfectible, if it would only follow its noblest ideals, and he preached racial harmony and integration. Malcolm X believed that the defining experience of black people in US society was not just of discrimination but of brutal oppression, and that separatism was the solution. King rejected violence; Malcolm X urged black people to defend themselves "by any means necessary". King said, "I have a dream"; Malcolm X said, "I don't see any American dream; I see an American nightmare."

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

American empire: a history of US imperial expansion

American empire: a history of US imperial expansionDonald Trump’s 21st century take on the Monroe Doctrine harks back to an earlier era of US interference in Latin America

-

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa Parks

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa ParksIn The Spotlight Inspired by the example of 19th century abolitionists, 15-year-old Colvin refused to give up her seat on an Alabama bus

-

Decking the halls

Decking the hallsFeature Americans’ love of holiday decorations has turned Christmas from a humble affair to a sparkly spectacle.

-

Hitler: what can we learn from his DNA?

Hitler: what can we learn from his DNA?Talking Point Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator is the latest documentary to posthumously diagnose the dictator

-

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025The Explainer From prehistoric sunscreen to a brain that turned to glass, we've learned some surprising new facts about human history

-

Malcolm X vs Martin Luther King: rivalry that supercharged the Civil Rights movement

Malcolm X vs Martin Luther King: rivalry that supercharged the Civil Rights movementIn Depth The two Civil Rights leaders had radically opposing but important approaches to the fight for equality, rights and justice for Black Americans

-

How did Kashmir end up largely under Indian control?

How did Kashmir end up largely under Indian control?The Explainer The bloody and intractable issue of Kashmir has flared up once again

-

The fall of Saigon

The fall of SaigonThe Explainer Fifty years ago the US made its final, humiliating exit from Vietnam