Malcolm X vs Martin Luther King: rivalry that supercharged the Civil Rights movement

The two leaders had radically opposing but important approaches to the fight for equality, rights and justice for Black Americans

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This article and interview originally appeared in All About History magazine issue 96. "The Sword And The Shield" by Dr Peniel E Joseph is available from Basic Books.

They didn't hold high public office, they didn't fight wars and they didn't possess vast wealth and riches. Yet, Dr Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X still managed to become two of the most iconic figures of the 20th century.

Rising to prominence at the height of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, each became equally revered and reviled by different parts of the United States.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Both would ultimately come to be the de facto leader of their groups and each would meet an untimely and violent end at the hands of assailants whose identities and motives continue to be hotly debated.

In Dr King's role as first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Malcolm X's position as a minister and leading national spokesperson for the Nation of Islam (NOI), these two men often appeared to offer two conflicting arguments and approaches to the challenge of achieving racial justice and equality in America.

What's more, each existed in the public eye to a far greater and wider extent than any of their contemporaries fighting for African American rights and representation, and as a result each has developed their own legend.

To discover more about the lives of these two men, as well as what linked or divided them All About History magazine spoke with Dr Peniel E Joseph, an author, scholar and public speaker who holds a joint professorship at the LBJ School of Public Affairs and the History Department in the College of Liberal Arts at The University of Texas at Austin.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"The mythology around both men frames them as opposites," he explains. "It frames Malcolm as Dr King's evil twin. It frames Dr King as this saint who would just give everybody a hug if he was alive right now and that really takes away from understanding the depth and breadth of their political power, their political radicalism and their evolution over time."

Early years of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr

First let's consider where each man came from and how that might have informed his world view.

"Martin Luther King Jr is raised in an upper-middle class, elite household in Atlanta, Georgia," Joseph tells us. "His father is a preacher, his mother is present in his life and it's a very comfortable upbringing. Malcolm X is raised in Omaha and in Lansing, Michigan on farms, so he's a country boy.

"His father is murdered by white supremacists when he's six years old and his mother is put in a psychiatric facility, so he's a foster child by the time he's in elementary school.

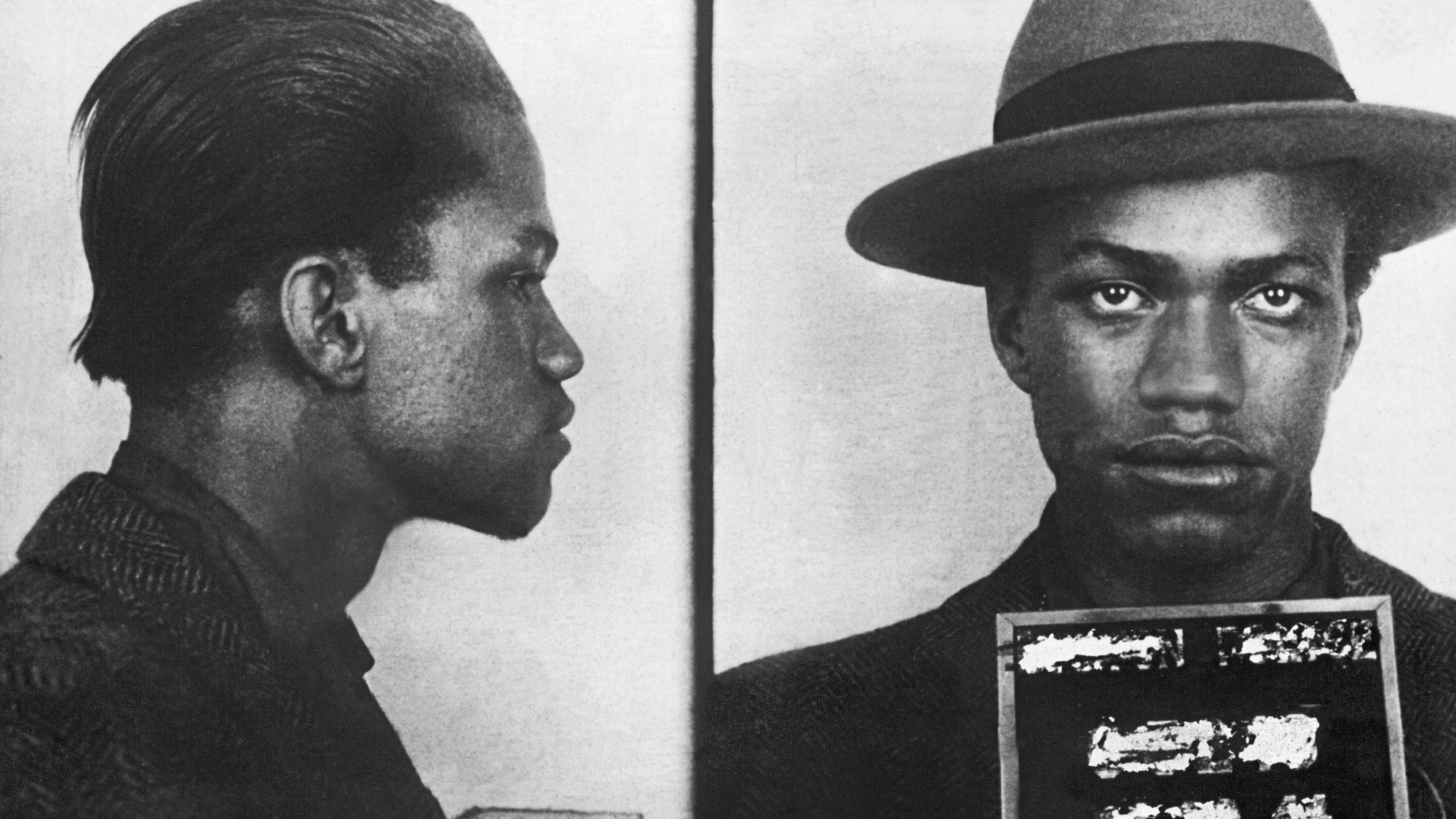

A mugshot of Malcolm X, then called Little, when he was arrested for theft aged 18

"Then he becomes a hustler in Boston and Harlem as a teenager and he's finally arrested for theft and spends seven years in prison," Joseph continues. "When Malcolm is in prison, Dr King is at Morehouse College, the most prestigious, historically Black, all-men's college that you could go to then or now.

"He goes and gets a theological degree at seminary school – Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania – and then gets a PhD at Boston University."

The strong religious upbringing of King clearly had a massive influence on his life, becoming a preacher himself as well as a political activist and integrating his faith deep into his speeches. Meanwhile, Malcolm's tough upbringing and the tragedies he endured help to explain the righteous anger and pain he expressed as a minister for the NOI.

However, Joseph does point out one curious similarity in their upbringing: "They're both impacted by the movie Gone With The Wind (1939). It premieres in Atlanta when Dr King is ten years old. Malcolm is 14 years old and sees that movie in Mason, Michigan, and talks about squirming in the movie theatre at all the racial stereotypes that the movie's filled with.

"It's filled with Black women who are servants who are getting slapped in the face by white women who are masters, and it's this sepia-toned, nostalgic vision of racial slavery. So that's similar."

It was during his time in prison that the then-Malcolm Little was introduced to Islam by some of his siblings and he joined the NOI. Its leader Elijah Muhammad took a personal interest in him, with letters being sent between them, before he was released in 1952.

He abandoned his 'slave name' of Little and became Malcolm X, a minister in the NOI advocating for Black separatism (which was the policy of the organisation), first in Chicago and later in Harlem, New York, which would become his base for years to come.

Two radically different approaches

The formative years of each man's life are ultimately what frames them as polarised voices in a similar struggle. "Malcolm X is really Black America's prosecuting attorney and he is going to be charging white America with a series of crimes against Black humanity," explains Joseph.

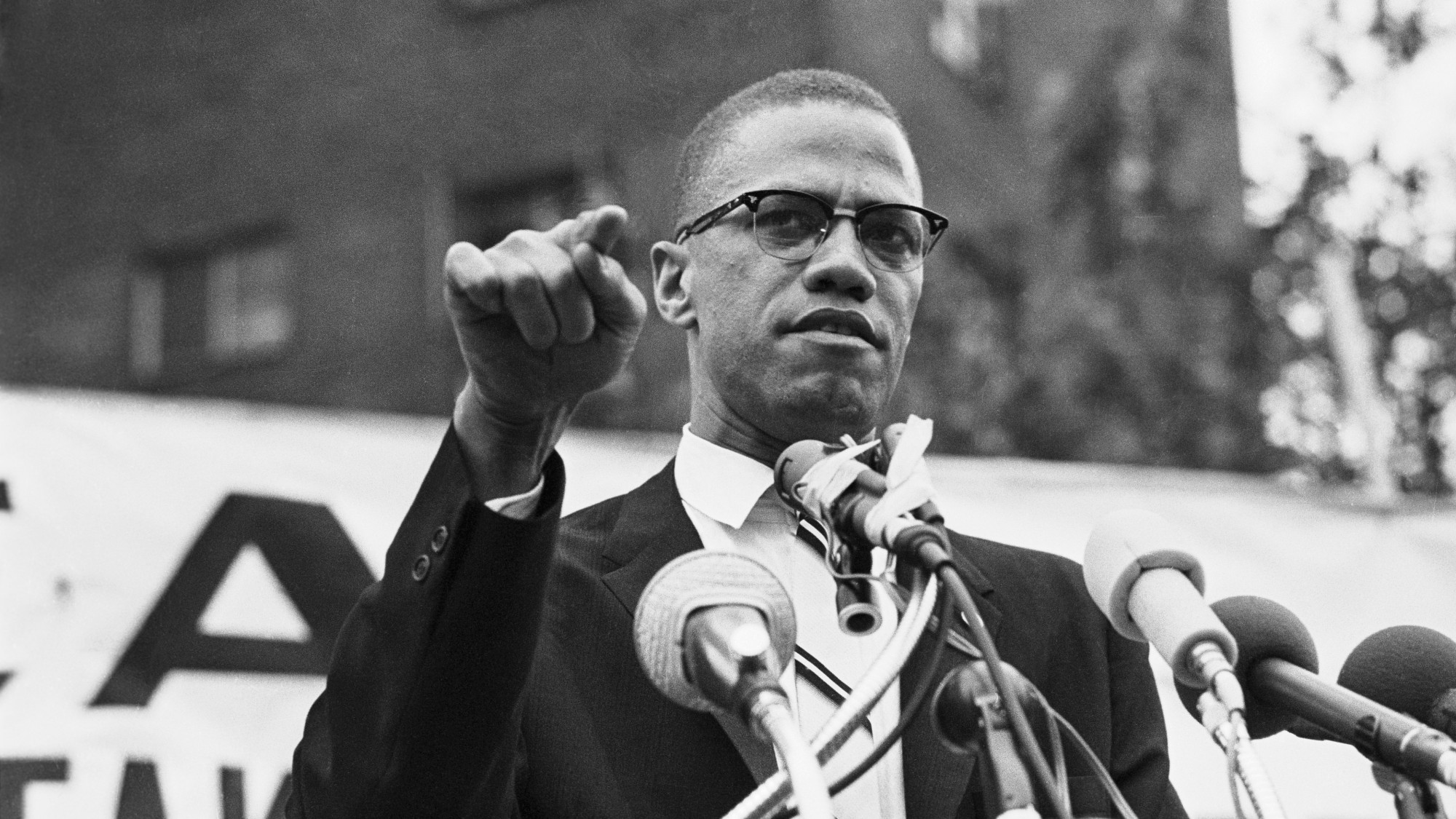

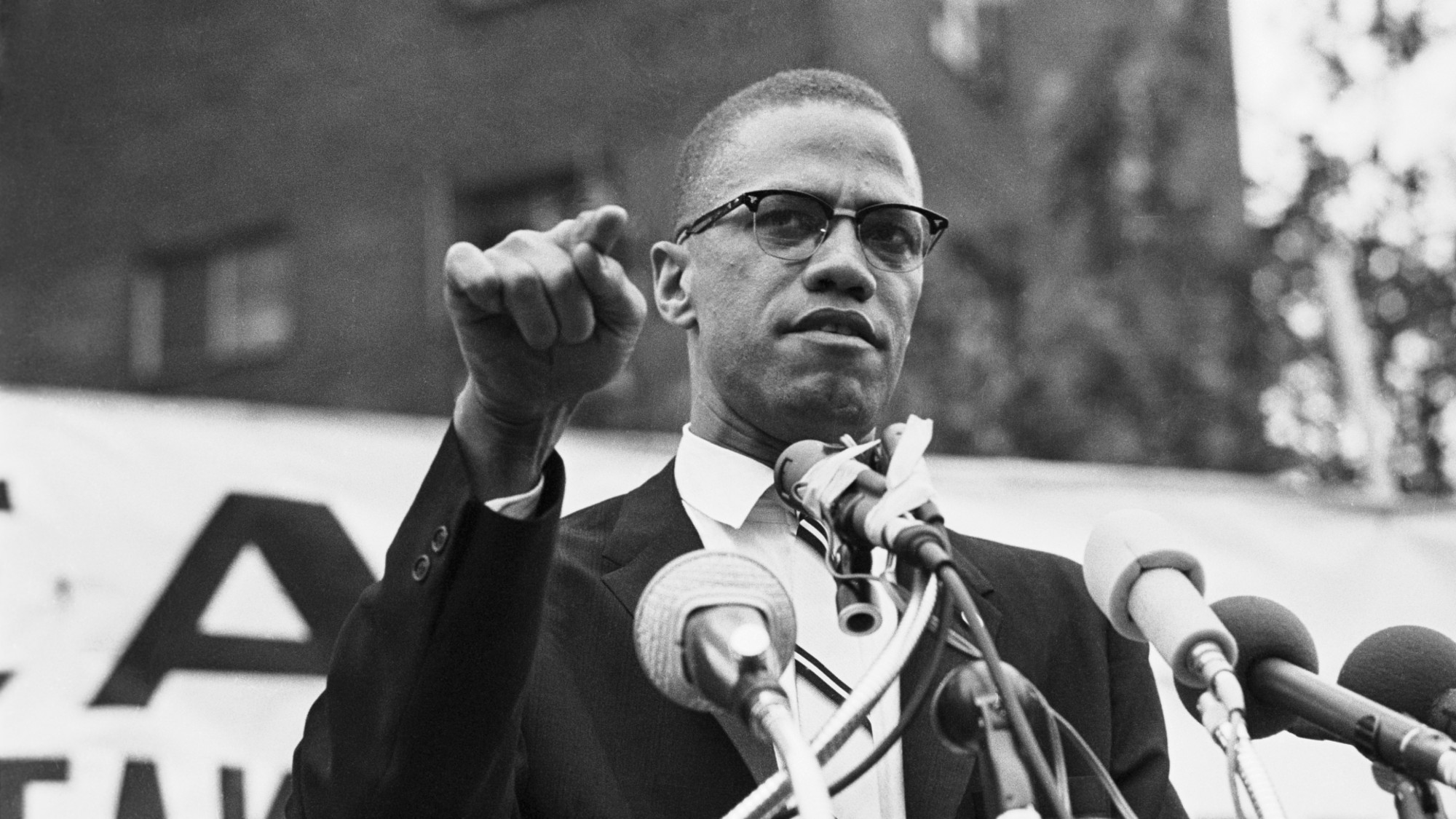

Malcolm X speaking at the Unity Rally in Harlem on 29 June 1963

"I argue in 'The Sword And The Shield' (Basic Books, 2020) that in a way his life's work boils down to radical Black dignity, and what he means by Black dignity is really Black people having the political self-determination to decide their own political futures and fates.

"They define racism and they define anti-racism and what social justice looks like for themselves. It's connected to the United States, but globally it's also connected to African decolonisation, African independence, Third World independence, Middle East politics, all of it."

Radical Black dignity is also, importantly, about building up a Black cultural identity that is independent of white America and building self-worth, which is a big part of where ideas like Black Power would later come from. King naturally comes to things from a different direction.

"Martin Luther King Jr is really the defence attorney," says Joseph. "He defends Black lives to white people and white lives to Black people. He's really advocating for radical Black citizenship and his notion of citizenship is going to get more expansive over time; it's going to be more than just voting rights and ending segregation. It's going to become about ending poverty, food justice, health care, a living wage, universal basic income for everyone."

So radical Black citizenship is about outward expression, about African Americans having an impact on the social systems that are in place, becoming engaged and demanding to be heard.

These two approaches, one that builds personal identity and another that looks to express that identity and have it recognised by a system that's set up to ignore Black voices, seem more complementary than adversarial when we look at them from a slight remove.

"Their differences really become differences of tactics rather than goals," says Joseph. "They're both going to come to see that you need dignity and citizenship and those goals are going to converge over time, but it's the tactics and how we get to those goals."

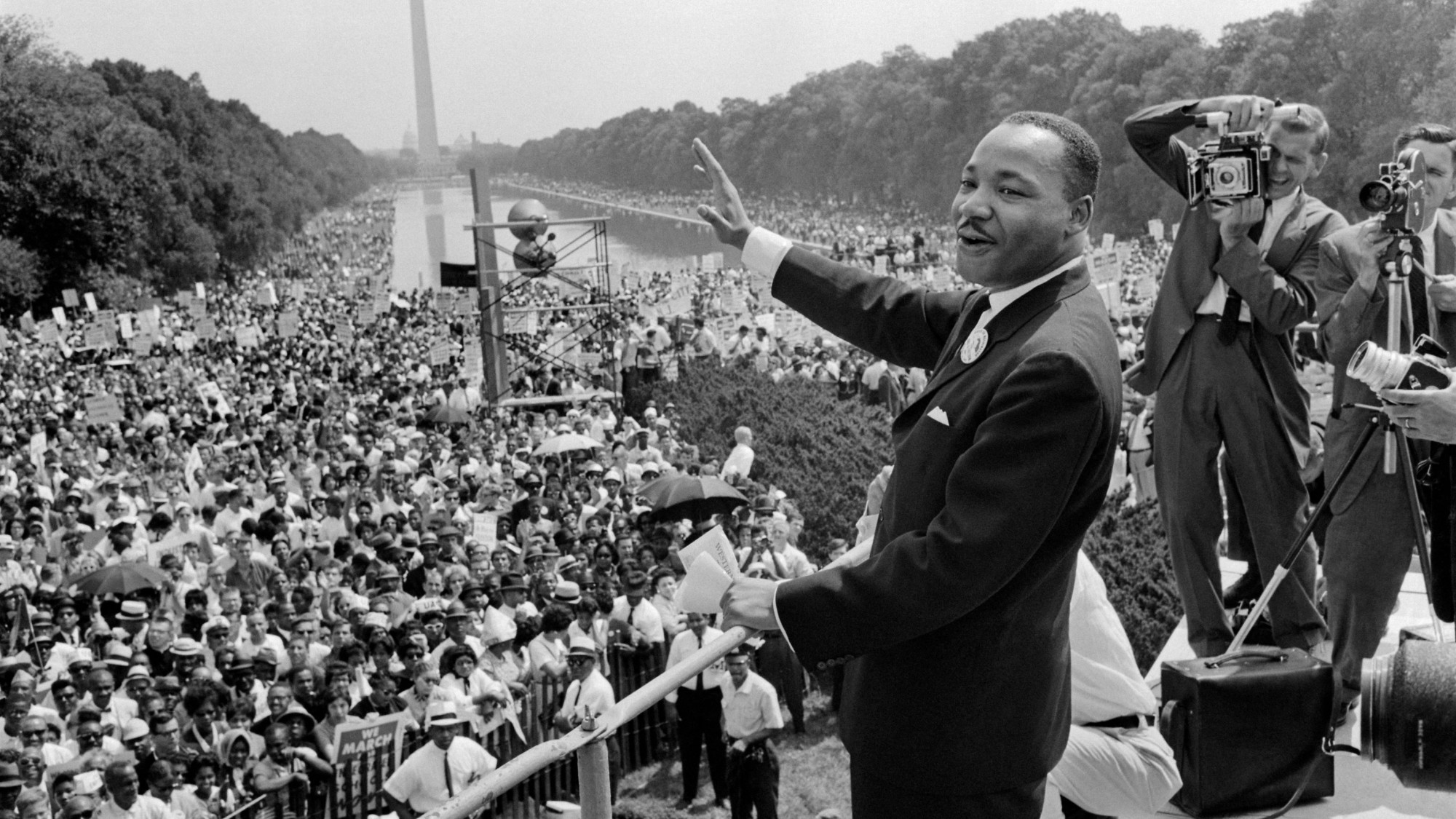

Martin Luther King Jr pictured during the March on Washington demonstration on 28 August 1963

Famously, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr did not always see eye to eye. Malcolm X in particular took aim at King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference on multiple occasions (likely because he was a high-profile target and Malcolm was nothing if not media savvy).

Malcolm regularly referred to King as an 'Uncle Tom', implying that his nonviolent strategy was either too accommodating to white America or even saying he was being subsidised by white America to keep African Americans defenceless.

King for his part warned, "Fiery, demagogic oratory in the Black ghettos, urging Negroes to arm themselves and prepare to engage in violence, as [Malcolm X] has done, can reap nothing but grief."

And yet despite the animosity between the two men publicly, Malcolm X continually attempted to reach out to King over the years. He sent articles and NOI reading materials and invited him to speeches and meetings.

On July 31, 1963, Malcolm X even publicly called for unity. "If capitalistic Kennedy and communistic Khrushchev can find something in common on which to form a United Front despite their tremendous ideological differences, it is a disgrace for Negro leaders not to be able to submerge our 'minor' differences in order to seek a common solution to a common problem posed by a Common Enemy," he wrote, inviting Civil Rights leaders to join him in Harlem to speak at a rally.

But they did not attend, perhaps because shortly after they would be attending the March on Washington and they were deep in planning. The slight was taken, though, with Malcolm dismissing the August 1963 event the 'Farce on Washington'.

Despite the rhetoric, Joseph thinks Malcolm was still learning much from King's activities. "Dr King is the person who helps mobilise Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 and King is going to be facing German Shepherds and fire hoses and it's going to be a big, global media spectacle," he says.

"King writes his famous 'Letter From Birmingham Jail' during that period. Malcolm is in Washington DC for most of that spring as temporary head of Mosque No. 4 there and he's really going to be influenced by King's mobilisations – his ability to mobilise large numbers of people – even as he's critical of King because of the nonviolence and the fact that so many kids and women are being brutalised."

Malcolm X and Martin Luther King meet

The really big shift in world view for Malcolm X came in 1964 as he gradually broke away from Elijah Muhammad (who was mired in allegations of extramarital affairs) and the NOI and sought to define his own path forward.

"By 1964 in 'The Ballot Or The Bullet' speech, you see Malcolm X talking about voting rights as part of Black liberation and freedom," explains Joseph. "You see him in an interview with Robert Penn Warren saying that he and Dr King have the same goal, which is human dignity, but they have different ways of getting there."

It's around this time that Malcolm X left the United States for several months, travelling to Egypt, Lebanon, Liberia, Senegal, Nigeria, Ghana and Saudi Arabia, including taking his pilgrimage to Mecca where he received his new Islamic name, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

The trip made a big impression on him, and he spoke subsequently about how seeing Muslims of so many different ethnic and cultural backgrounds worshipping together opened his eyes to the real possibility of racial integration and peace.

All of this actually took place not long after the two men had met for what would be the first and only time. In the midst of the passing of the Civil Rights Act, as it was being filibustered on the Senate floor, Dr Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X crossed paths on Capitol Hill.

Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X pictured during their first and only meeting, outside the US Capitol on 26 March 1964

"They both come and are talking to reporters and doing press conferences in support of the Civil Rights Act," says Joseph. "They're both coming there for the same reason. People are surprised that Malcolm is there and he's watching the Senate and he's doing his interviews and there's a point where Malcolm is in the same room as Dr King and on the couch while Dr King is doing his press conference and they meet afterwards, exchanging pleasantries."

It was a moment captured by only a couple of photos, catching them mid-conversation with Malcolm recorded as saying, "I'm throwing myself into the heart of the Civil Rights struggle."

Malcolm X continued to make overtures to King in the months that followed, offering him protection in St Augustine, Florida, that spring as protestors fought for desegregation of its beaches and playgrounds and later in Selma, Alabama, as King's attention turned to voting rights where he felt he had a role to play.

"I think Malcolm gave King more room to operate and I think Malcolm knew this," says Joseph. "When he visits Selma shortly before his own death, he's trying to visit Dr King in February of 1965 in Alabama, but King is jailed and he gets to visit Coretta Scott King, gives a speech and visits some of the student organisers.

"He tells Coretta Scott King that he's only there to support her husband and he wants people to know that if her husband's advocacy of voting rights is not accomplished that there are other alternative forces out there that are going to be led by him. So he definitely offers King more strategic leeway."

Impact of Malcolm X's assassination

Whether or not the two men could have ultimately found a way to coordinate their approaches in a less ad hoc fashion we will never know because on February 21, 1965, just days before the Selma to Montgomery marches were about to be attempted by King's movement, Malcolm X was assassinated in New York.

The impact of his death would be felt throughout the movement, and profoundly by King.

"One of the surprising things is that we don't discuss the way in which the person who is most radicalised by Malcolm's assassination is Martin Luther King Jr," Joseph explains.

"He breaks with Lyndon Johnson on April 4, 1967, with the Riverside Church speech in New York, where he says that the United States is the greatest purveyor of violence in the world. Malcolm had always talked about racial slavery and how racial slavery had shaped the present and King talks about that much more after 1965."

As King turns his attention to economic inequality through the mid- to late-1960s, he digs deeper and deeper into the wider historic inequalities and injustices of America. "He becomes this very prophetic, radical figure after Malcolm's assassination and he's much more interested in race and Blackness too," says Joseph.

"There's a speech he makes in 1967 where he says they even tell you 'A white lie is better than a Black lie'. He gets into it in a granular way; and this is King, not Malcolm. It's Dr King who says that the halls of the US Congress are 'running wild with racism'.

"King is testifying before the Kerner Commission, the president's riot commission, and talking about the depth and breadth of white racism," Joseph continues.

"He speaks to the American Psychological Association in September 1967 and says that white people in the United States are producing chaos, blame Black people for the chaos and say there would be peace if not for the chaos that they produce.

Crowds gather outside the Audubon Ballroom, New York City, aheads of Malcolm X's speech on 21 February 1965

"He's really much more candid and much more blunt, much more radical, much more revolutionary and there are no more meetings with the president of the United States."

It is perhaps because they evolved and were willing to learn from one another that each has remained as relevant today as they were in the 1960s. The question that hangs around them, though, is could either of them have achieved as much as they did if the other hadn't been there challenging them?

"I think they both need each other," concludes Joseph. "They both have misapprehensions about each other and they make mistakes about each other. King thinks Malcolm is this narrow, anti-white Black nationalist. Malcolm thinks King is this bourgeois, reform-minded Uncle Tom when they start out. Neither of them are those things, so they both needed the other."

What's more, the contributions of each remain important to this day. "Dr King is this major global political mobiliser and the way in which he frames this idea of racial justice globally is very important, and the numbers he attracts are very important," says Joseph.

Meanwhile Malcolm has perhaps given us much of the vocabulary around racial justice even in the 21st century: "Malcolm is the first modern activist who is really saying Black lives matter in a really deep and definitive way and becomes the avatar of the Black Power movement."

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa Parks

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa ParksIn The Spotlight Inspired by the example of 19th century abolitionists, 15-year-old Colvin refused to give up her seat on an Alabama bus

-

The assassination of Malcolm X

The assassination of Malcolm XThe Explainer The civil rights leader gave furious clarity to black anger in the 1960s, but like several of his contemporaries met with a violent end

-

How Black History Month began

How Black History Month beganIn Depth Annual celebration dates back almost 100 years