Vladimir Putin’s narrative of Russian victimhood examined

Russian president has repeatedly pointed to his country’s history to justify Ukraine invasion

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

History Professor Robert Frost of Aberdeen University on how Putin is using Russia’s past as a propaganda weapon

Russian president Vladimir Putin sees his country’s history as providing the essential justification for the war he is waging against the Ukrainian people. He has long used history as a propaganda weapon. In his rambling address on the eve of his invasion of Ukraine, he claimed that Ukraine’s independence has separated and severed “what is historically Russian land”. He also said “nobody asked the millions of people living there what they thought”.

Putin is not known for asking those he rules what they think about anything. Nevertheless, his tendentious vision of Russian history is shared by millions of Russians.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

According to Putin, Russia has always been a blameless victim of foreign aggression, heroically repelling invaders and foreign attempts to destroy Russia. Notable examples he often uses include the 1612 Polish-Lithuanian occupation of the Kremlin; the invasions of Charles XII of Sweden in 1708–9 and Napoleon in 1812; the Crimean War, and Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa in 1941.

That last example helps explain the considerable sympathy for the Russian version of history in many Western circles. The decisive role of the Soviet Union in defeating Hitler is remembered with gratitude by many among the generation who lived through the Second World War, and by many on the Left. In consequence, despite Putin’s aggression in Chechnya, Georgia and the Crimea, there has been no shortage of influential commentators urging that we must see things through Russia’s eyes and understand Putin’s fear of invasion.

This view of Russian history is one-sided and highly selective. In every case cited above, it could be argued that these invasions followed, or were responses to, acts of aggression by Russia itself.

Putin has also repeatedly referred to what Russians call “Kyivan Rus”, a medieval state centred around the Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv. The Rus people were the ancestors of contemporary Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians. Putin, like many Russians, considers that these three nations are one, with Ukrainians and Belarusians merely “younger brothers” of Russians.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Grand Duchy of Muscovy (Moscow) was only one of the successor principalities of Kyivan Rus, and one that remained longest under Mongol overlordship. Ever since it threw off Mongol overlordship in the reign of Ivan III (1462–1505), Russian rulers have pursued a grand imperial vision. They claimed that they were the rightful inheritors of the legacy of Kyivan Rus’, which was destroyed by the Mongols in the 13th century.

Yet when Ivan III first claimed to be ruler of all Rus, which meant all of what had been Kyivan Rus, the vast majority of that territory was ruled by the grand dukes of Lithuania. They had extended their protection and rule over Kyiv and most of the Rusian principalities after the Mongol conquest.

In contrast to Ivan III and his successors, who were building a ruthless autocracy, the pagan Gediminid dynasty (who ruled the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Kingdom of Poland from the 14th to the 16th century) operated an uncentralised system of rule. Junior princes were assigned Rusian principalities, converted to the Orthodox church, married local princesses and assimilated to Rusian culture.

This system of self-government was far more in the political tradition of Kyivan Rus than Muscovite autocracy, while the Rusian language itself is the ancestor of modern Belarusian and Ukrainian. It was the grand duchy’s legal language, since Lithuanian was not a written language until the 16th century. After 1386, Lithuania’s negotiated, consensual union with Poland brought enhanced legal rights. From 1569, the union’s powerful parliament limited royal power, and encouraged religious tolerance of the Orthodox church.

When Ivan III launched the first of five Muscovite-Lithuanian wars fought between 1492 and 1537, he did not ask Lithuania’s Orthodox inhabitants what they thought. He claimed the lands of all Rus, but although Muscovy’s aggression secured a third of Lithuania by 1537, these lands were sparsely populated. And the Orthodox inhabitants of the core Belarusian and Ukrainian lands preferred liberty to autocracy.

In September 1514, Kostiantyn Ostrozky, the greatest Orthodox magnate in what is now Ukraine, destroyed a much larger Muscovite army at the battle of Orsha, and built two Orthodox churches in Vilnius to celebrate his victory.

Russians paid a heavy toll as Ivan all but destroyed the country’s economic and military systems, and the Kremlin occupation came at the height of a Muscovite civil war in which substantial numbers of boyars (barons) elected the son of the king of Poland as their tsar.

Charles XII’s ill-fated invasion of Russia came eight years after Peter I launched an unprovoked attack on Sweden’s Baltic possessions. And Napoleon’s invasion was supported by tens of thousands of Poles and Lithuanians seeking to restore their republic, illegally wiped off the map in three partitions between 1772 and 1795. In each case, Russia had played an aggressively assertive role.

The Crimean War was also a response to Russian aggression against the Ottoman Empire. Finally, Hitler’s invasion of 1941 was preceded by Stalin’s unprovoked and cynical invasions of Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland in 1939–1940.

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is the latest in a series of acts of naked aggression by Russian rulers against the country’s neighbours, justified by grand imperial claims and a well-established and questionable narrative of victimhood.

Robert Frost, Professor of History, University of Aberdeen.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

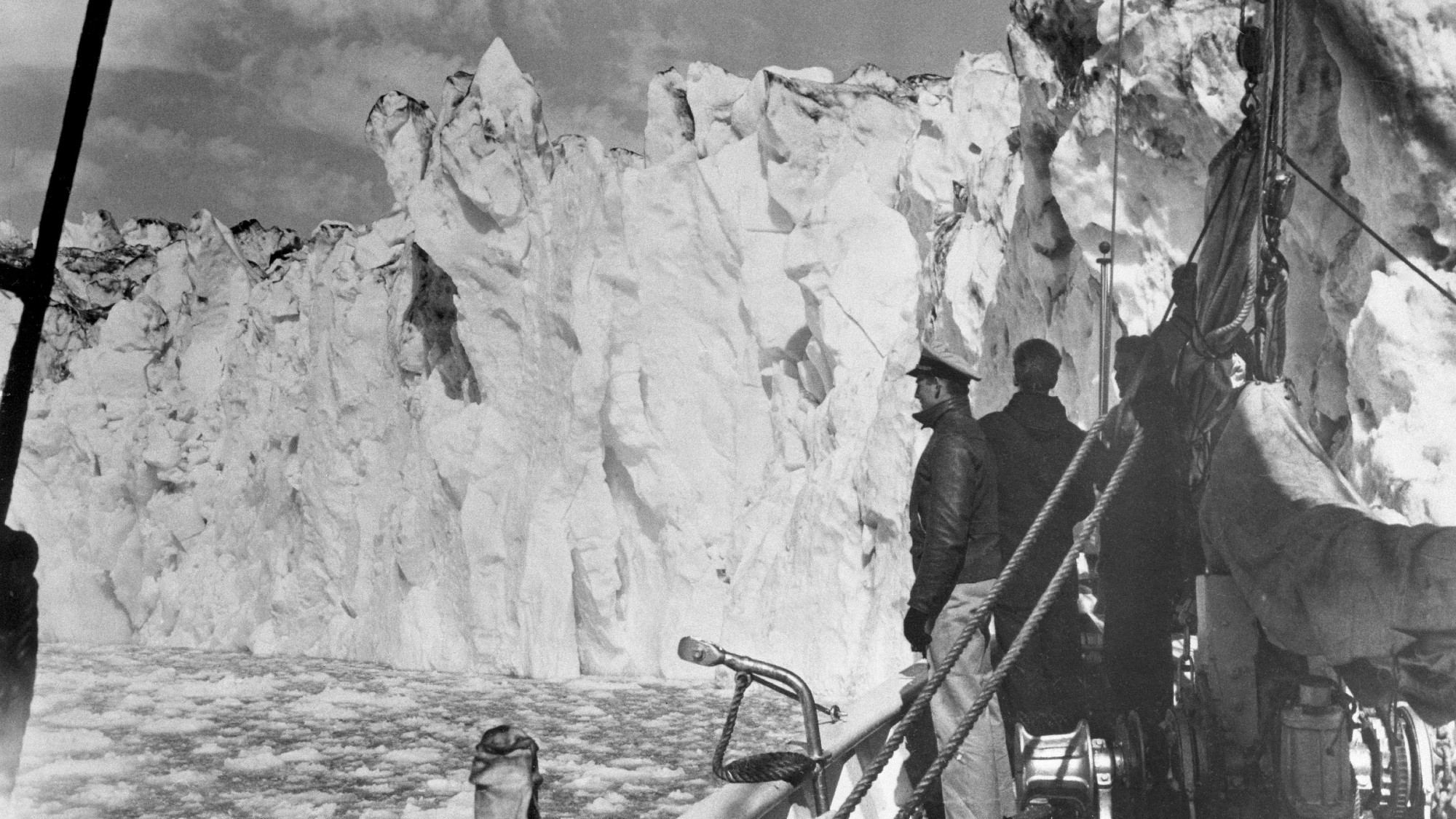

Why Greenland has been a US military stronghold since the Second World War

Why Greenland has been a US military stronghold since the Second World WarIn Depth American interest in acquiring Greenland is rooted in decades of military and economic strategy

-

Has Putin launched the second nuclear arms race?

Has Putin launched the second nuclear arms race?In Depth Historian Serhii Plokhy explains why the Kremlin’s nuclear proliferation has begun a dangerous new era of mutually assured destruction

-

How China rewrote the history of its WWII victory

How China rewrote the history of its WWII victoryIn Depth Though the nationalist government led China to victory in 1945, this is largely overlooked in modern Chinese commemorations

-

How Putin misunderstood his past victories

How Putin misunderstood his past victoriesIn Depth Though Vladimir Putin has led Russia to a number of grisly military triumphs, they may have misled him when planning the invasion of Ukraine

-

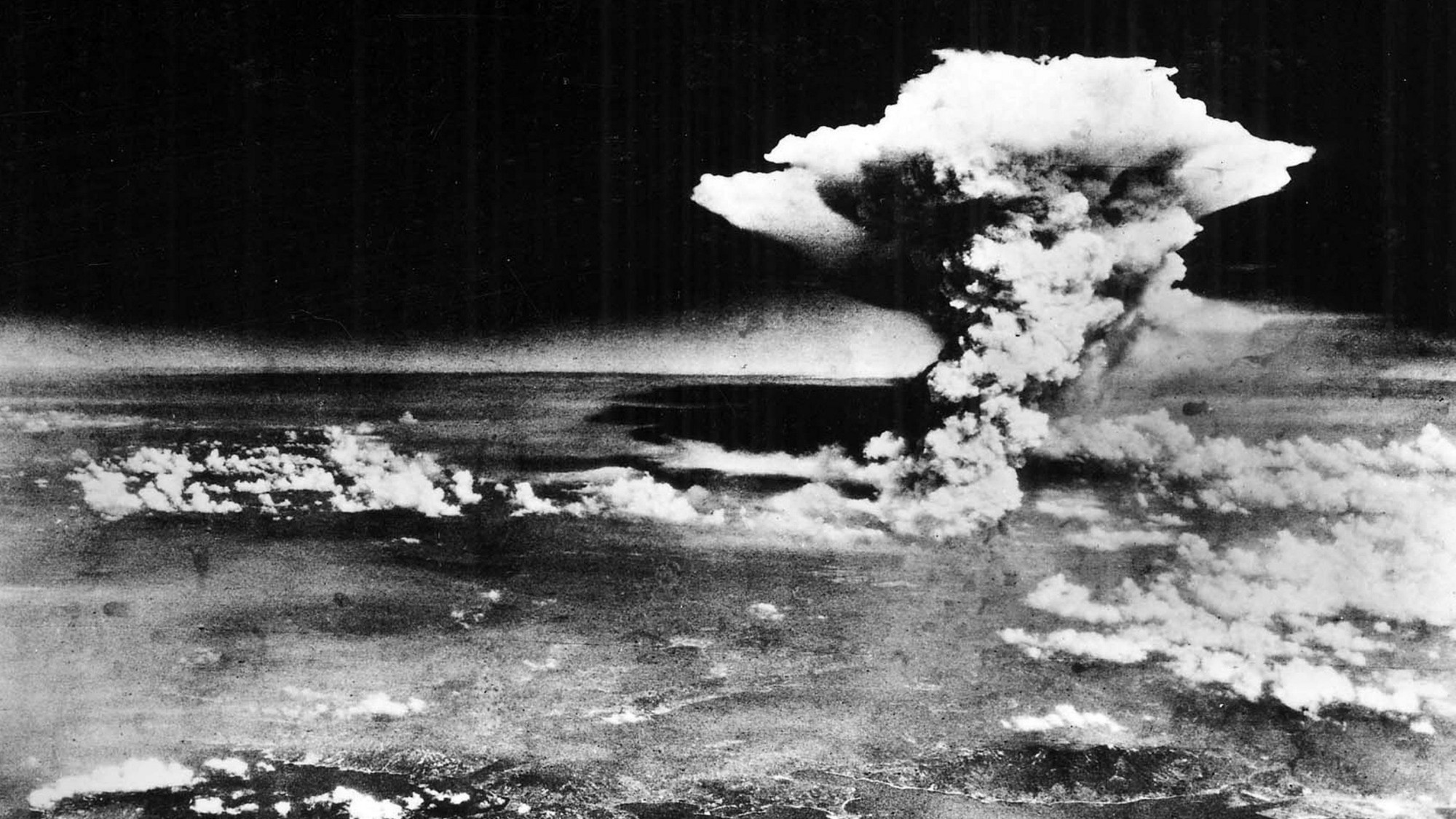

America's controversial path to the atomic bomb

America's controversial path to the atomic bombIn Depth The bombing of Hiroshima followed years of escalation by the U.S., but was it necessary?

-

Mutually Assured Destruction: Cold War origins of nuclear Armageddon

Mutually Assured Destruction: Cold War origins of nuclear ArmageddonIn Depth After the US and Soviet Union became capable of Mutually Assured Destruction, safeguards were put in place to prevent World War Three

-

Argentina lifts veil on its past as a refuge for Nazis

Argentina lifts veil on its past as a refuge for NazisUnder the Radar President Javier Milei publishes documents detailing country's role as post-WW2 'haven' for Nazis, including Josef Mengele and Adolf Eichmann

-

D-Day: how allies prepared military build-up of astonishing dimensions

D-Day: how allies prepared military build-up of astonishing dimensionsThe Explainer Eighty years ago, the Allies carried out the D-Day landings – a crucial turning point in the Second World War