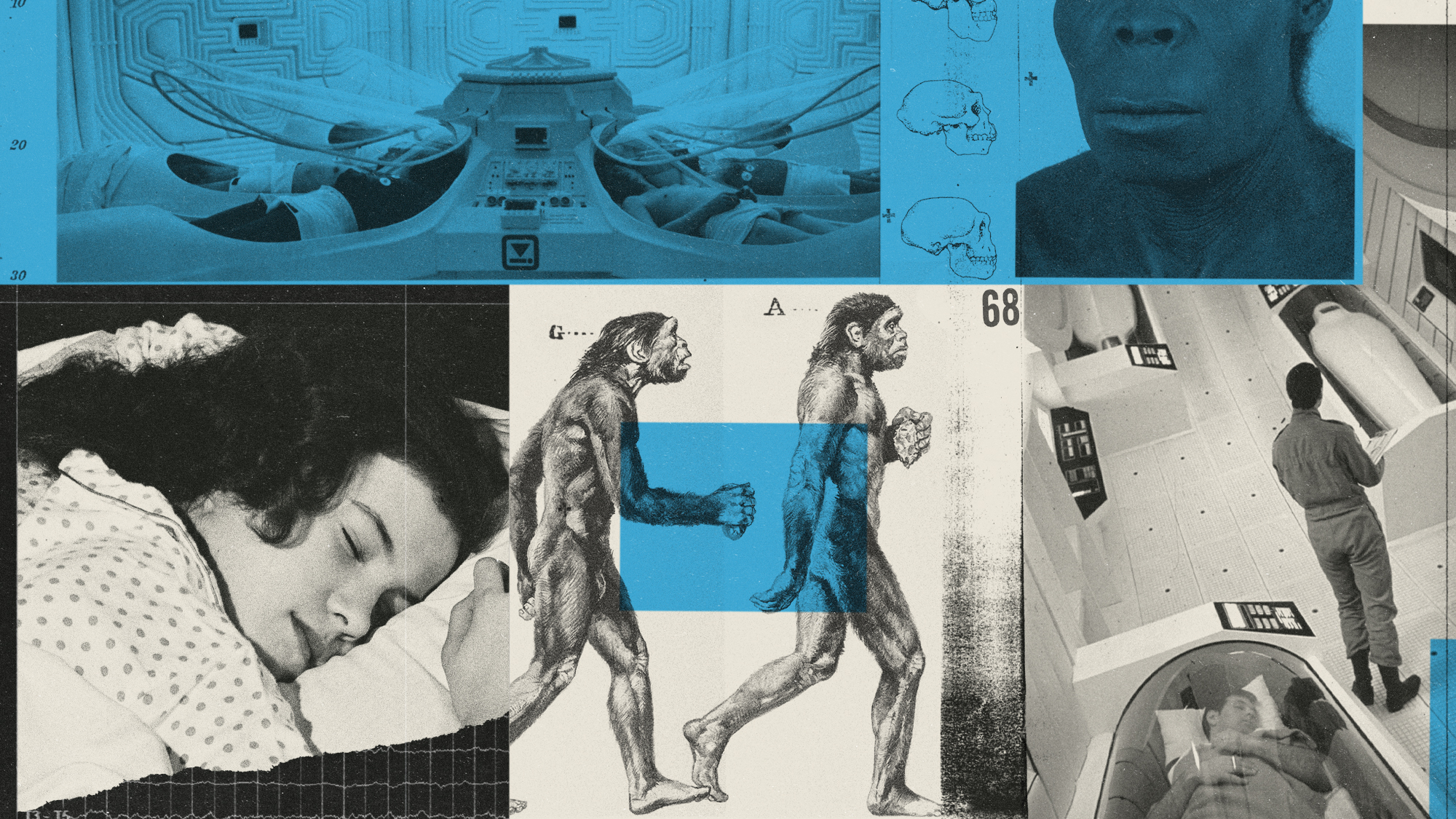

Why don’t humans hibernate?

The prospect of deep space travel is reigniting interest in the possibility of human hibernation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As the mercury plummets and back-to-work blues set in for much of humankind in the UK, many other creatures are cosily spending winter in a blissfully dormant state of hibernation.

It would be easy to envy bats, bears and hedgehogs their seasonal torpor, but research has suggested that humans once hibernated, too – and scientists believe we may one day do so again.

Why don’t humans hibernate?

It’s mostly a question of time and geography. Our evolutionary ancestors were “tropical animals with no history of hibernating”, said BBC Science Focus. There is evidence of various migrations out of Africa but modern humans, homo sapiens, only migrated into the cooler “temperate and sub-Arctic latitudes” (where hibernation in winter is more common among other species) “in the last 100,000 years or so”. In evolutionary terms, that isn’t “quite long enough” to develop “all the metabolic adaptations we would need to be able to hibernate” for lengthy periods of time.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Have humans ever hibernated?

It‘s long been assumed not. After all, humans “discovered fire, clothes, shelter, hunting and agriculture”, and these are “much more effective ways of surviving the cold” than hibernating for months on end. It’s been taken as read that any “ancient tribes that tried to sleep their way through the winter” would have been swiftly “ousted” by “the guys with the fur clothes sitting around the camp fire in the next cave along”.

But this may not be the complete picture, scientists suggested in a 2020 study, published in the journal L'Anthropologie. They analysed more than 1,600 fossilised bones of hominins (extinct ancestors of modern humans), found in Spain and dating back around 500,000 years. They looked at factors “like bone structure and growth over time to backform” what these people “were eating and doing during the seasonal cycle”, said Popular Mechanics.

Their conclusions pointed to this extinct human species spending a lot of time inside caves, particularly “through the cold and difficult winter months”. Evidence of recurrent nutritional disease and bone weakening indicate that these human ancestors “sacrificed nutrition and vitamin D from the sun” in order to “spend the worst part of the year trying to sleep through it inside relatively safe caves”. Not exactly hibernation – but close.

Will humans ever hibernate in the future?

The possibility of modern-day human hibernation straddles the realm of “both science and science fiction”, said Aeon. The prospect has “always captivated us” but we haven’t yet had an “immediate or urgent need to do so”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That could be about to change. “Putting people into sleep mode is a sci-fi concept that’s a lot closer to becoming real than you might think,” said National Geographic.

Nasa and the European Space Agency are supporting research into trials that use carefully dosed sedatives to put participants into “a state that mimics some of the key features of hibernation”, including a drastically slowed metabolism and a “twilight” state of consciousness that still allows for biological functions like eating, drinking and using the toilet. Being in a “bearlike state of hibernation” could help astronauts on future deep space missions, alleviating “the tedium of extended space travel”, reducing cargo requirements and limiting “crewmate conflict”.

It could have far-reaching effects in medical settings, too. “Controlled hypothermia and metabolism are already widely used in clinical practice” to reduce damage to the body and provide optimal conditions for complex medical interventions, said neuroscientist Vladyslav Vyazovskiy on The Conversation. The difference is that, for now, a hibernation-like state can only be achieved in humans with “the aggressive use of drugs”.

Chas Newkey-Burden has been part of The Week Digital team for more than a decade and a journalist for 25 years, starting out on the irreverent football weekly 90 Minutes, before moving to lifestyle magazines Loaded and Attitude. He was a columnist for The Big Issue and landed a world exclusive with David Beckham that became the weekly magazine’s bestselling issue. He now writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Metro, FourFourTwo and the i new site. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books.