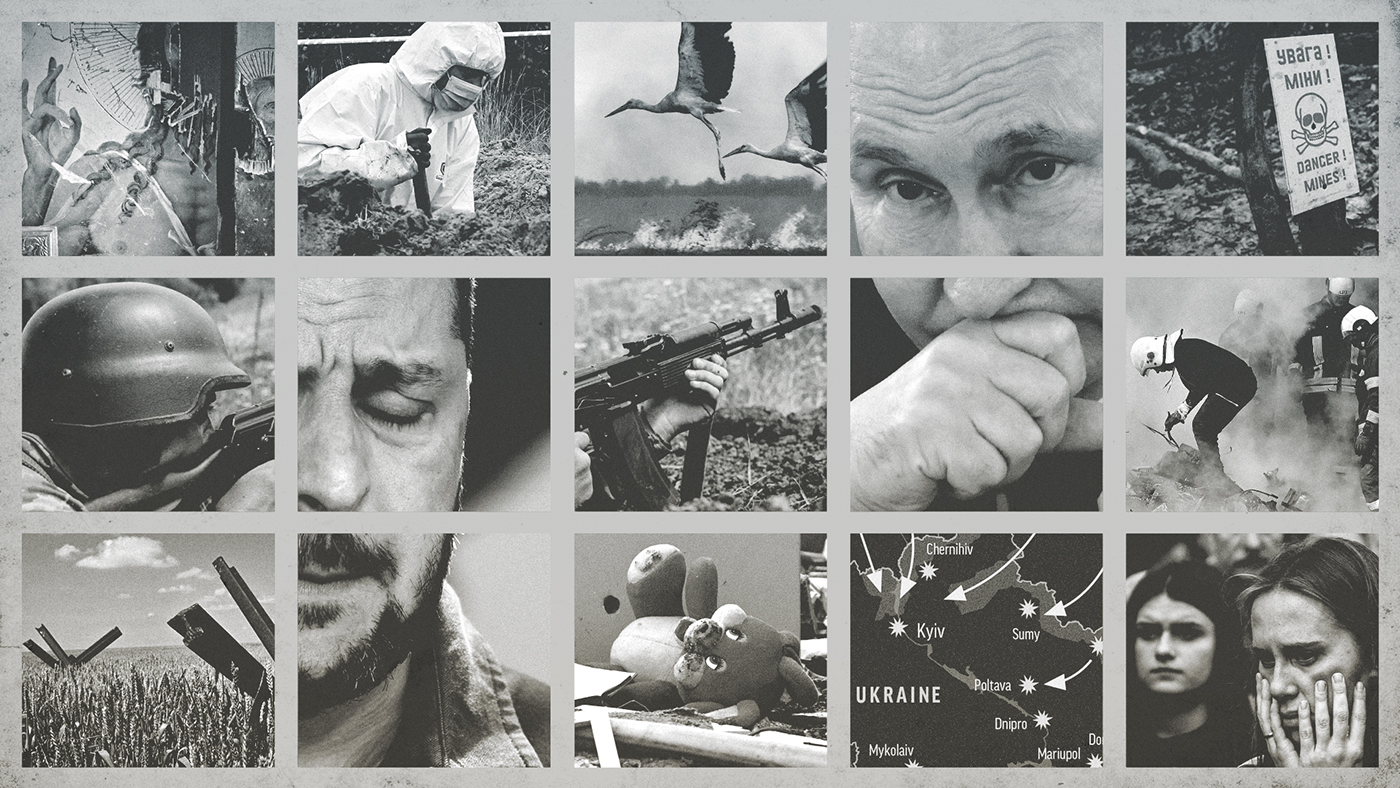

Who is winning the war: Russia or Ukraine?

As the conflict enters its fifth year, both sides can point to small victories but the overall picture has barely changed

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Four years after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began, the war that Moscow hoped would be over in a matter of days has now dragged on longer than the Soviet Union’s involvement in the Second World War.

Outside Russia, the invasion on 24 February 2022 “was widely seen as an attempt to force Kyiv back into Moscow’s orbit and to overturn the entire post-Cold War security architecture in Europe”, said the BBC’s Russia editor Steve Rosenberg. “The Russian leadership envisaged a short and successful military operation. It didn’t go to plan.”

As the war “grinds on”, each side has claimed small victories but the overall picture has barely changed.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Can Ukraine win the war?

As the fighting enters its fifth year, the war is increasingly likely to be decided by two key factors: the supply of soldiers and maintaining international support.

Ukraine’s “inherent weakness is that it depends on others for funding and arms”, said the BBC’s international editor, Jeremy Bowen. On the other hand, Russia “makes most of its own weapons” and is “buying drones from Iran and ammunition from North Korea” with no limitations on how they are used. It also enjoys an advantage in raw manpower, bolstered by massive conscription drives.

Vladimir Putin aims to have a bigger army than America’s, with 1.5 million active servicemen, “a sign of Russia’s relentless militarisation”, said Sky News’ Moscow correspondent Ivor Bennett.

Its superiority in personnel and materials – along with the use of new “infiltration tactics”, reported by Deutsche Welle – has seen it make steady but slow progress on the battlefield.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

After “seizing the initiative” in 2024, last year Russian forces advanced at an average rate of between 15 and 70 metres per day, “slower than almost any major offensive campaign in any war in the last century”, said the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) think tank.

In truth, Russia is “having more success obliterating Ukraine’s electricity grid and municipal heating plants, leaving civilians shivering in sub-zero cold, than it is securing any decisive victory on the battlefield”, said Radio Free Europe.

The suggestion by Putin and senior Russian government and military figures that Ukraine’s front line faces “imminent collapse” is a “false narrative”, said the Washington-based Institute for the Study of War. Such claims are likely to be “an effort to coerce the West and Ukraine into capitulating to Russian demands that Russia cannot secure itself militarily”.

What does victory look like for each side?

Before Russia launched its invasion, Putin outlined the objectives of what he called a “special military operation”. His goal, he claimed, was to “denazify” and “demilitarise” Ukraine, and to defend Donetsk and Luhansk, the two eastern Ukrainian territories occupied by Russian proxy forces since 2014.

Another objective, although never explicitly stated, was to topple the Ukrainian government and remove President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. “The enemy has designated me as target number one; my family is target number two,” said Zelenskyy shortly after the invasion. Russian troops made two attempts to storm the presidential compound.

Russia shifted its objectives, however, about a month into the invasion, after Russian forces were forced to retreat from Kyiv and Chernihiv. According to the Kremlin, its main goal became the “liberation of the Donbas”, including the regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia.

The Trump administration’s initial 28-point plan published at the end of last year suggested Russia’s “minimum requirement” remains “occupying the entirety of the Donbas region (comprising the provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk)”, said The Economist. Most contentiously, this includes territory it has so far failed to take by force. Other provisions include limits on the size of Ukraine’s army and missile capability, and barring it from Nato membership or hosting Nato peacekeepers on its soil.

Kyiv was quick to denounce these demands as amounting to capitulation and countered with its own 20-point framework. This proposed security guarantees from the US, Nato and European countries to prevent further Russian aggression, with the potential option of establishing a demilitarised “free economic zone” in eastern Donbas.

While this represents a softening of Ukraine’s position, it is still unlikely to be palatable to Putin. The Russian president would gladly have taken as a win a “Kremlin-friendly peace plan that enshrines Ukraine’s perpetual subordination”, said The New York Times. But he’ll also see “a failed process” as a victory if it leads Donald Trump to “pull remaining support for Ukraine”. With his economy struggling and his troops mired in a slow advance that’s had a steep cost in “lives and matériel”, Putin’s capacity for continued war “isn’t limitless”. But he believes “time is on his side” and his goal hasn’t shifted: he “wants to break Ukraine”.

How many Russian and Ukrainian troops have died in the conflict?

True casualty figures are “notoriously difficult to pin down”, said Newsweek, and “experts caution that both sides likely inflate the other’s reported losses”.

As of January this year, Russian forces had suffered “nearly 1.2 million casualties”, which would mark “more losses than any major power in any war since World War II”, said CSIS. “At current rates, combined Russian and Ukrainian casualties could reach 2 million by the spring of 2026.”

Ukrainian casualty tolls – including deaths, injuries, and soldiers classified as missing – are around 500,000 to 600,000, compared to Russia’s 1.2 million, said Brad Lendon of CNN.

This is a dramatic increase, even within the last year. In June, Russia’s wartime toll reached a “historic milestone”, said The Guardian, with more than a million troops killed or injured since the start of the invasion, according to the UK Ministry of Defence. Russia Matters cited MoD estimates for October 2025 that put the number of Russian soldiers killed or wounded at 1,118,000.

Russian authorities do not release official casualty figures but the “huge battlefield losses” are clear for all to see, said Rosenberg. “So many of the towns and villages I’ve visited in the last two years have had museums and monuments dedicated to soldiers killed in Ukraine, as well as separate sections for recent war dead at local cemeteries.”